Gesaria Armenian Research and Academic Services unlocks the Armenian past

In a world where much of Armenian history remains locked away in fading family letters, dusty archives and complex handwriting styles, two UCLA-trained historians are working to bring those stories back to life. Jennifer Manoukian and Daniel Ohanian, both specialists in Ottoman-Armenian history, have recently launched Gesaria Armenian Research and Academic Services (GARAS), a unique public history company that connects past and present through translation, research and education.

Their mission is clear: to unlock the vast reservoir of Armenian heritage trapped in Armenian-language memoirs, audio recordings, personal letters and postcards that many descendants struggle to read or understand today. From translating handwritten notes sprinkled with French and Turkish words to offering online language lessons tailored to scholars and eager learners of all ages, their work breathes new life into the past, turning hazy histories into accessible, meaningful stories.

What began as a personal journey of discovery gradually evolved into a professional project that bridges the gap between academia and the public. By supporting families, academics and cultural institutions through translation, editing and research expertise, GARAS not only preserves heritage but also creates opportunities for Armenian identity, culture and history to be rediscovered, reinterpreted and celebrated — one word at a time.

Milena Baghdasaryan (M.B.): What inspired you both to launch this initiative? Was there a specific moment or experience that sparked your deep interest in translation and Armenian history?

Jennifer Manoukian (J.M.): Daniel and I are both historians. We completed our Ph.D.s at UCLA and specialize in Ottoman-Armenian history. While finishing our degrees, we noticed significant interest outside academia in learning about this history, especially in deciphering family documents written in difficult-to-read scripts and handwriting styles no longer in use. Our own research had given us hands-on experience with similar materials, so we started our company to share the knowledge we had gained during our doctoral work and to kindle more interest in this fascinating history with so many unexplored parts.

Daniel Ohanian (D.O.): There wasn’t one eureka moment for us. During the preceding 10 years or so, people had been hiring us informally for different kinds of editing and translation projects. Launching this company was a way to build on that — to make our work more systematic and to devote more of our time to supporting our clients’ projects. As our Ph.D. programs were ending, launching GARAS felt like a logical next step.

M.B.: The name Gesaria is quite distinctive. Can you explain its significance and why you chose it to represent your work together?

J.M.: Daniel and I both trace our roots to the region around the city of Gesaria, or modern-day Kayseri. I trace part of my ancestry to the village of Moundjousoun, and many of Daniel’s ancestors lived in the city of Gesaria itself and in the nearby towns of Everek-Fenese and Akdağ Madeni. We thought naming our company Gesaria would be a nice way to pay tribute to this past.

M.B.: What do you enjoy most about the work that you do?

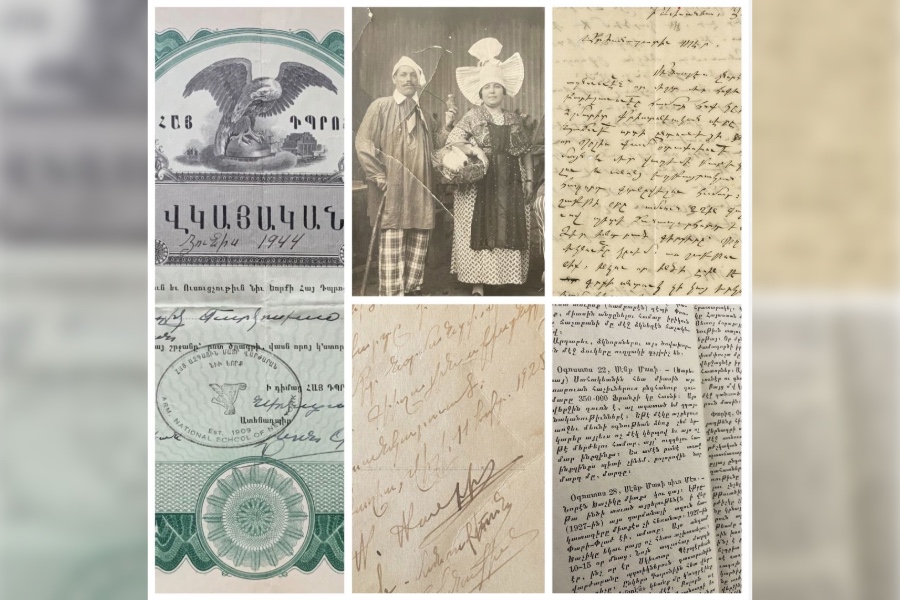

J.M.: It’s really exciting to be entrusted with materials that might have been in a box, attic or drawer for a very long time. It’s exhilarating to use our skills to help decode these materials and give people a whole new piece of their family history that they can then explore further.

M.B.: Can you describe the types of clients you typically work with? Are most of them families, academics, institutions or others? How do your services meet their different needs?

J.M.: It’s a mix. Many individuals contact us directly with an editing or translation project, big or small. Other times, professors, graduate students or curious lifelong learners will write to us looking for language training in Western Armenian — not always to learn to speak conversationally but often to read historical sources. We have also been hired to work on transcription and translation projects involving oral history recordings with family members long ago; on editing side-by-side with the original English translations from Western Armenian; on cataloguing soon-to-be-donated personal libraries; and on writing family history reports, based on Armenian-language sources, to help people better understand the lives their ancestors led in Aintab, Kharpert, Bitlis, etc. Archives and research centers with backlogs of materials have also reached out to us with large-scale and small-scale cataloging projects.

D.O: We also enjoy working with non-academic writers on passion projects at all stages of the writing process. This includes everything from developing early drafts to offering detailed feedback on already drafted work to polishing their English prose. One reason people come to us is because we’re able to strengthen the historical rigor of their work and guide them to sources — historical materials as well as modern scholarly research — that they can use to enrich their writing even more.

M.B.: Handwritten documents often pose unique challenges. Could you explain what makes them particularly difficult to translate?

D.O.: There are at least two challenges. One is the style of handwriting: whether it’s neat or messy, modern or archaic and idiosyncratic. The other challenge is linguistic. Today, Armenians write in Western or Eastern Armenian, but in the past, people often wrote in now nearly extinct regional dialects or very colloquially, using a mix of different languages.

M.B.: Have you found your work to be predominantly focused on the genocide period, or do your projects span broader themes and eras?

J.M.: Initially, we expected to receive many genocide survival accounts, but most of our projects so far have been from other periods — accounts of early Armenian life in America in the early 1900s; letters from the 1940s written by a father in Ethiopia to his son at boarding school in Cyprus; snapshots of daily life in pre-genocide Marash and more. Armenian history encompasses much more than just the genocide, and we are seeing this reflected in the projects that have come through so far.

M.B.: Of all the projects you have undertaken, which would you describe as the most significant or impactful, whether in scale, historical importance or personal meaning?

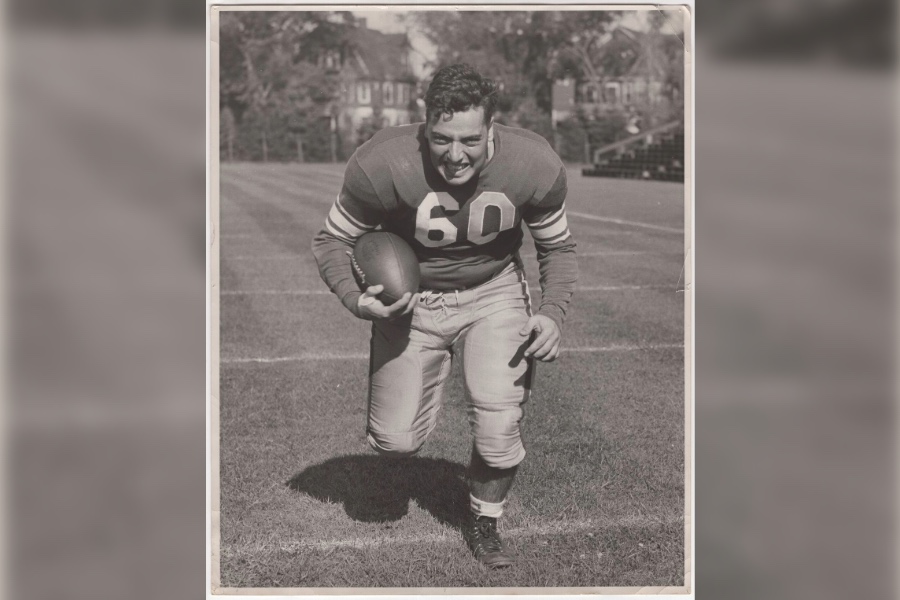

D.O.: A big one was finishing the cataloging and publication of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation Archives’ historical photograph collection. The collection is amazing. It starts in earnest around 1900 and ends in the 1970s. It includes everything from photos of fedayees to Armenian-American college football players.

It’s a very rich collection that adds so much to our collective understanding of the many nuances and transformations that have happened in recent history.

M.B.: Your clientele is quite international. How do people typically discover your services? Have you engaged in targeted marketing, or does word of mouth within the Armenian diaspora play a bigger role?

J.M.: Our clients have come from all over: the United States, Canada, Armenia, Lebanon and the United Kingdom, to name a few. When we were just starting, we sent emails to people we knew in academia — colleagues and friends from the network we had developed over the past 15 years. That’s how we first got the word out.

D.O.: Now, a lot of it is by word of mouth. The diaspora is incredibly transnational, so someone we’ve worked with in Canada might recommend us to a contact in Italy, for example. Clients who weren’t referred to us directly have mostly found us on LinkedIn or through online searches.

M.B.: When you first launched, how did initial feedback shape the direction or scope of your services? Were there unexpected client needs that required you to adapt?

J.M.: We were pleasantly surprised by the positive feedback right from the beginning, but we did learn and adapt by clarifying and expanding our offerings based on new types of projects that we were approached with and that matched our skill set.

We started offering a three-session ‘Getting to Know Your Ancestral Dialect of Armenian’ course, after seeing so much interest in exploring the kinds of Armenian that Armenians spoke in Dikranagerd, Arapgir, Sassoun or elsewhere.

We also realized that there was a particular interest among certain speakers in strengthening their reading skills to, for example, read literature in the original Armenian and appreciate it on a whole new level.

For us, this means focusing on developing specific skills and vocabulary rather than conversational fluency. Often, it also means teaching elements of Classical Armenian, which is not typically covered in Western Armenian classes geared toward conversation.

Based on feedback, we also began offering an online crash course in the Armenian alphabet for people who might be able to speak Western Armenian but who never had the opportunity to learn to read and write.

This is very common in parts of the United States, especially among certain generations who spoke Armenian at home growing up but never had the chance to go to Armenian school and gain literacy in the language. With these students, their introduction to the Armenian alphabet often seems to open the floodgates of memory and bring back sights, smells and sounds they had not thought about in decades!

M.B.: Working closely as life partners and professional colleagues can be complex. How do you navigate your joint roles in the company to maintain productivity and harmony?

D.O.: It’s really, really fun. Our processes are like a Venn diagram. Some of our projects are collaborative and others we work on separately. But even in the case of the separate projects, we overlap because we ask each other for advice. For example, if I’m deliberating between two possible words for a translation, I can go to Jennifer and say, “Which of these sounds more natural to you? How would you translate this?”

M.B.: What unique strengths and perspectives do each of you bring to the company that complement each other?

J.M.: My academic interests lie in how Armenians used and thought about language in the Ottoman Empire and post-genocide diaspora. I’m very language-minded. I’ve been a literary translator from Western Armenian for 15 years and am a learner of Armenian myself. I didn’t grow up with the language at home and started learning it in my teens. Because of this, I like to think that I bring a certain empathy and lack of judgement to my language lessons.

I know the stumbling blocks, like letters that look nearly identical, or the intimidation that can surface early on in the learning process when encountering a wall of Armenian text on the page.

D.O.: My strengths are in the history of Armenian religion, the Classical Armenian language (գրաբար) and Modern and Ottoman Turkish. Turkish is crucial, not just for deciphering the loanwords that appear so often in the letters that our clients send us; it’s also important as a research language. There’s a lot of important work for Armenian studies that is published in Turkey in Turkish. We give our clients access to that academic ecosystem. Naturally, we also pull from French, alongside Eastern and Western Armenian and English, when we’re hired to curate bibliographies, write family history reports, etc.

M.B.: What message would you like to share with Armenians around the world, particularly those interested in exploring their heritage or engaging with Armenian language and history?

J.M.: Have fun with Armenian things! It is not all sad, dusty and depressing. There is so much color, light and human drama to be found in the Armenian past when you look off the beaten path.

D.O.: I would say this to those who, like me, grew up inside an Armenian community: After a certain number of years, many of us come to think that we know it all, that we’ve heard or read it all. But graduate school showed me that that is never the case. Reading more, and reading in multiple languages, leads you to stories that you could never have imagined existed. Even more excitingly, it can make you re-think and re-conceptualize so much that you had previously taken for granted.

re Kayseri/Gersaria

my father was aged 7 when his father was hanged as he was from a prominent family, fathers other brother was born 1895

l would be pleased to share info on this