Background

This is a two-part tale of two Armenian brothers from Detroit: the eldest Haigus during World War II and the youngest Hagop (Jack) during the Korean War. It is a story of the Tufenkjians, an immigrant Armenian family who came to America after the Armenian Genocide, and their offspring, who were born in the early 1920s. Two of the oldest of them found themselves of draft age in 1942 after Pearl Harbor.

The Armenians of Detroit were primarily west siders; in fact, the vast majority, including the Tufenkjians, lived in southwest Detroit, which we referred to by its postal zone designation, Zone 9. This little Armenian world was subdivided into four distinct sections.

Beginning in the industrial part of south Dearborn, under the shadow of the historical four Ford smokestacks of the Rouge Plant, was Salina Street with its Armenian, Kurdish and Arabic restaurants and coffee houses. The mosque meets the end of the Woodmere Cemetery, where the Armenians are buried. This is where the Detroit city limit starts and Vernor Hwy. begins. “Highway” is a misnomer — Vernor is a busy two-lane city street that splits off of Dix Road and goes about three miles east to the first Armenian section called Clark Park.

The park was only two narrow blocks wide, bounded on the east by Clarke Street and the west by Scotten Street, a busy commercial thoroughfare. The 18-story Michigan Central Train Station is right down the street on Vernor Hwy. Today it is being refurbished by the Ford Motor Co. to its former glory after being abandoned for more than 60 years.

The Tufenkjian family resided in a two-family house on Ida, an east-west street that dead ended into Scotten Street two short blocks south of Vernor Hwy. Today, Ida Street is long gone due to the expansion of the high school. At that time, Western High School was right behind their house, and the kids had the whole park to enjoy in their youth. A five-minute walk from their home through Clark Park brought them to Christiancy Street, and another three blocks went to Ferdinand Street and the ARF Mourad Agoump, where there was a coffee house and the AYF Mourad Chapter met.

The park was narrow, but if you went three city blocks south on Scotten Street to Lafayette Street and turned right, you would reach the third Armenian section at the corner of Lafayette and Waterman, anchored by the ARF Hye Getron. The Armenian Community Center (ACC) building, affectionately known as Findlater, was designed as a four-story monumental masonic temple.

The Hye Getron was purchased by the ARF in 1940 and thereafter became the center of Armenian life in every respect. It was a church inside of a temple. It had two large halls, one for banquets and one for dances, and a theater with a stage. The Hye Getron had several organizational meeting rooms, including the AYF game and TV room, a museum and of course, the Armenian school. Finally, there was the coffee house and card room.

So, the Tufenkjian family lived very close to all of the Armenian community activities.

From Hye Getron, it is only a mile to the fourth Armenian section, the Delray Section, only two short blocks west to Green Street, then south through Fort Street to Jefferson Avenue. Each of these streets comprise the seven radial spokes that lead you to downtown Detroit. One short block before Jefferson, turn right on Cottrell Street to reach the ARF Zavarian Agoump, which is on the left at the corner of Erie Street. Here again, the story is the same as the ACC. There was a church, Armenian school, a hall with a stage, library, coffee house and card room. The Zavarian Agoump, the home of the Zavarian AYF, was built by the ARF in 1928-29 and was sold in the late 1960s after the Armenians of the Delray Section left Detroit in the mid- to late-1950s for the inner suburbs of Metro Detroit.

From the 1920s through the early 1960s, there were three other Armenian centers: the Hai Getron on Ferry Street in Pontiac near Jessie, the ARF Club at 77 Victor Avenue adjacent to the historic Ford Model T plant off Woodward Avenue in Highland Park, and last, but not least, the St. John Armenian Church, built in 1932 on Oakman Blvd. Around the corner on Linwood Avenue was the ARF Azadamard Club, home of the AYF Christopher Chapter, also known as the Civic Center building. All of these locations and facilities have long been abandoned, including the Tufenkjian family residence.

In 1960, both of the Armenian churches of the day moved 10 miles north and west to just outside the city limits — St. John to the city of Southfield and St. Sarkis and the ACC to Dearborn. Today, the ACC has purchased 40 acres of land in Novi and is planning to relocate 20 miles to the north and west, following the flight of our people. This may not be the typical Armenian community story, but it is the history of the Armenians of Detroit.

I hope you enjoyed this travelog through the past and that it brought a nostalgic smile to the faces of the present and former Detroiters old enough to recall fond memories of dinner dances and plays at the Zavarian, the Findlater and the Cultural Hall on Oakman Blvd.

Today, a couple of former Clark Park Armenians are khnamees (in-laws) of the Tufenkjians: Mike Manoogian of Philadelphia and his sister Elizabeth Vartanian of Springfield, Massachusetts, and their families.

Manos and Marie Tufenkjian’s family lived on Ida Street in Detroit in 1941. They had four children, three boys and a girl. As this story begins, the siblings, in order of their age, are Ghazaarn (John), age 26, Haigus, age 20, Angelle, age 19, and Hagop (Jack), age 12. The primary protagonists of this two-part story are Haigus, who became a five-star hero during World War II, and his younger brother Jack, who was in the Korean War a decade later between 1950-53.

Jack and the Korean War

This July 4 holiday weekend commemorates 73 years since Jack Tufenkjian’s participation in the Korean War in 1951. Hagop, or Jack as he was known, had two special powers that separated him from most of us. The first was that Jack was a musician, which was useful to him in the service; the second and more important will be revealed at the end of the story. Jack was a big band drummer. He told me at a church bazaar that he changed his legal name from Hagop Tufenkjian to Jack Tian before he went into the service to match his new stage name, because Tufenkjian did not fit well on the face of his bass drum. At that time, he did not realize it would later disguise his heritage when it could have been a problem.

The Korean War began on June 25, 1950, with the invasion of North Korea into South Korea, The U.S. and many countries of the United Nations came to its defense. At the time, Jack was a healthy 21-year-old and a primary candidate for the U.S. military draft, as both of his older brothers were during WWII. While he was in the Induction Center, it was common practice, especially at the beginning of the Korean War, for a person with selection authority to go down the line of inductees and tap every fifth person on the head to announce that they would go into the U.S. Marines. This is when Jack’s first special power came into effect. As a drummer, Jack joined the U.S. Marine bands, which afforded him the accompanying advantages of that service, thankfully.

After the war, Jack married a fellow Clark Park Armenian girl, Stella Manoogian, who lived around the corner on Scotten Street where her father Zakar had a barber shop, now a Latino district. They had three children, all Detroit AYF champion swimmers: two boys, Manse and Aaron, and a daughter Dawn.

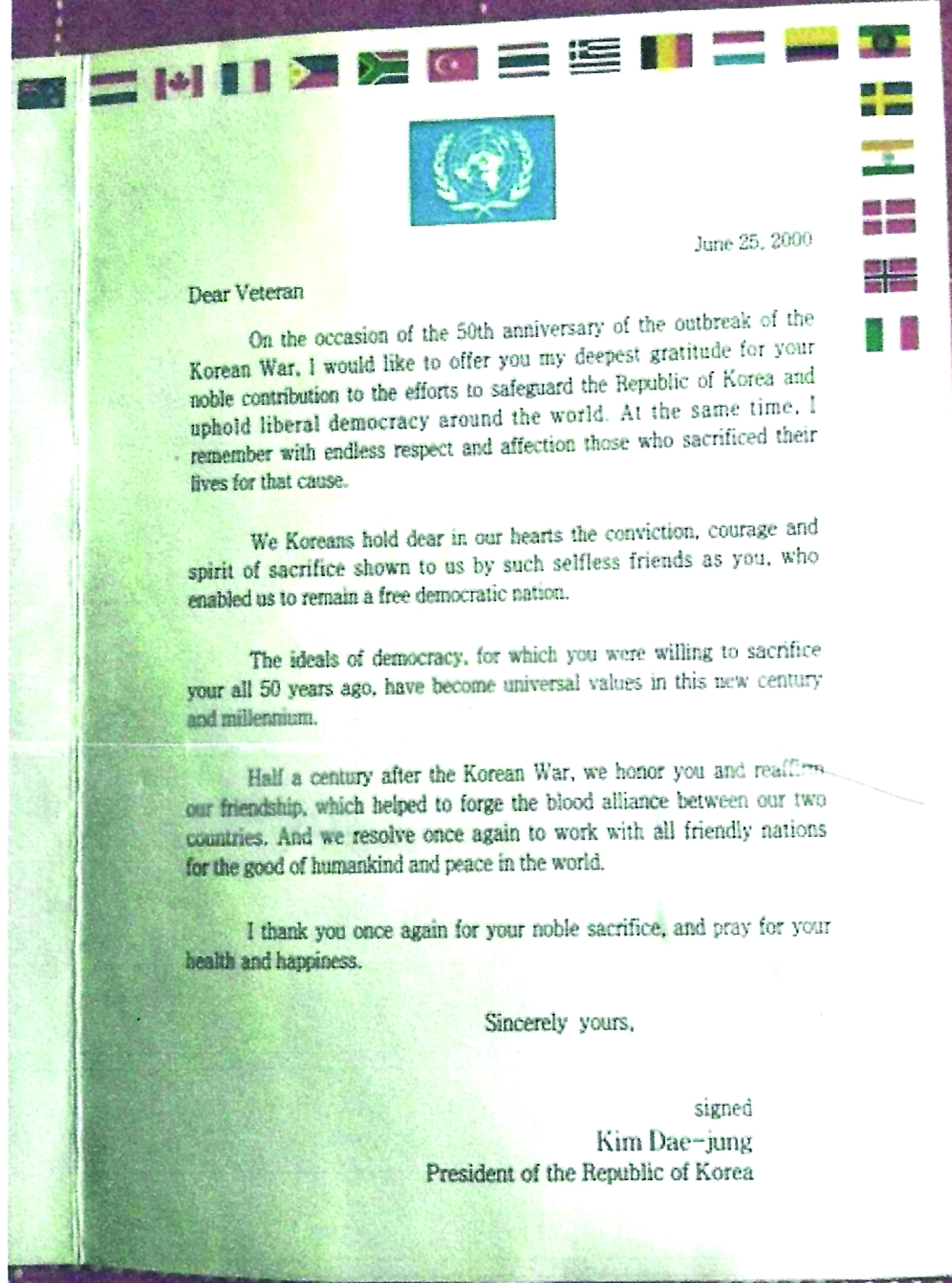

In the year 2000, 50 long years had passed since the start of the Korean War, and the South Korean government commemorated its anniversary. Sometime around June 25, 2000, the Tians received a package at their home at 15543 Blue Skies Street in Livonia, Michigan.

The unexpected package was addressed to Jack Tian and contained two letters of commendation, both artistic in their design, one in Korean and the other in English. Neither of them were addressed to Jack but to “Dear Veteran.” Also included with the two distinctive letters was a Korean War Service Medal. Needless to say, Jack called all of his Armenian and non-Armenian veteran friends to see if any of them received a similar package. Much to his surprise, none had!

He told me the following story, which he thought must be the reason for this much-appreciated recognition by the South Korean government a quarter century after his service. He was in the mess hall in late 1951 and heard an announcement over the loudspeaker stating that, due to the United Nations involvement in the war effort, the Marine Corps was looking for Marines who were bilingual in any language. He applied and eventually was accepted by the translating section of the Marine Corps.

For over a year, Jack was assigned to the Turkish Army in Korea as an official Marine interpreter. I am not sure at what level his translating occurred, whether at the highest echelons of the Turkish army or with the common soldiers. All I know is that Jack never spent a day in Turkey! He did say that the Turks were very impressed that an American knew Turkish. When he left his service, one of the Turkish officers told him that if he didn’t know any better, based on his accent he could swear that Jack was from his district of Yozgat in Turkey.

Well, Jack’s father and mother, Manos and Mari Tufenkjian, were in fact from Yozgat, and I am sure they knew Armenian very well. But they were a Turkish-speaking household, which was not uncommon in those days. Jack was a proficient Turkish speaker, which was his second special power and the reason for his Korean Letter of Commendation and Medal. Jack did not grow up knowing Armenian; he learned Armenian when he married into the Stella Manoogian family.

Today, all the major protagonists of this story are long gone. May their memories shine bright with all of those who still remember them.

Part two of the story will feature Haigus Tufenkjian in honor of the 80th anniversary of his heroic sacrifice on August 26, 1944 in Germany during World War II.

Hi Ned, I enjoyed reading this very interesting story… I’m glad that you took your time and write about this episode…

Great job Ned. A lot of heavy duty research went into this project. Abrees!

Nice article Ned, it was great conversing with you while you were putting it together. A few things I’d like to clarify in honor and remembrance of our grandparents, their names were Manase & Anoosh Tufenkjian.

I would also like to add that our father was one the premier drummers in the Detroit area. He was also fortunate to play and recorded with the likes of Art Madigan, Charlie Byrd Parker, Dave Brubeck, Oliver Nelson, Bobby Rodriguez, and Pancho and his Orchestra. If you followed jazz in the Detroit area (late1940’s thru 2008) you may have caught him playing at the Bluebird Inn, Bakers Keyboard Lounge, Cliff Bells or a private party.

Thank you, Aaron for sharing that extra bit of information about your father playing and recording with these well-known musicians.

WOW! This brouht back so many fond memories of my life in Detroit. I was born in 1924 in Highland Park. I celebrated my 100th year at the Armenian Festival in Ranch Mirage , CA

My Grandfather was a Village Traveling Priest in Sivas, Turkey. My mother was born in

Sarioglan Turkey witch is half way between Kaiseri and Sivas.