Special Issue: Genocide Education for the 21st Century

The Armenian Weekly, April 2023

1. A photograph is many things. It’s a snapshot of a moment and an echo of a memory. In older photographs, it’s both what’s in the photo and the materiality of the photo itself–a valuable, often uncanny object in its own right. Photographs can document and amplify historical events. They can also explore notions of beauty, mystery, time and mortality. Photographs are so visceral and direct that they can elicit empathy and connections among people who might otherwise not understand or know one another’s stories. A powerful photograph will usually do all of the above.

In communities that have been historically oppressed and scattered, photographs have a vital added function–they are witnesses. And that has been the driving force behind Project SAVE Armenian Photograph Archives, to save and share the dynamic narrative of the Armenian world through photographs and the stories they tell so that they won’t be forgotten.

Founded in 1975, Project SAVE is the largest archive in the world solely dedicated to photographs of the Armenian global experience. Its collections contain over 80,000 hardcopy, original photographs spanning over 160 years and several continents.

Today, the visual image has become a dominant, ubiquitous global language due to intense technological and cultural changes to the point where we take photographs for granted. But in the late 1960s, Project SAVE’s founder Ruth Thomasian instinctively understood the universal impact and importance of photographs, especially when she noticed that in the Armenian world there was little to no focus on preserving and documenting them. Without realizing it, she would become one of the most unique, pioneering individuals in the field of Armenian cultural work.

Decades later, Project SAVE has become one of the important photography archives in North America.

2. It’s 1903 and fourteen members of the Palanjian family have gathered in a photo studio in Yerzinga to have a portrait taken. Sitting for a photograph at that time is still mostly for the privileged, so they’re dressed impeccably, like any middle to upper class Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. The children and grandchildren are gathered around the matriarch who lovingly holds the infant on her lap. Three of the children grip wildflowers casually in their tiny hands. Two of the girls have big white bows in their hair. Shooshanig, the younger one, sits on the edge of a chair by her mother, feet dangling. Years later, she’s the only one who would survive the Genocide. But for now, as the photograph is snapped, the warmth and bond between them all is evident in their eyes and demeanor. They are full of hope.

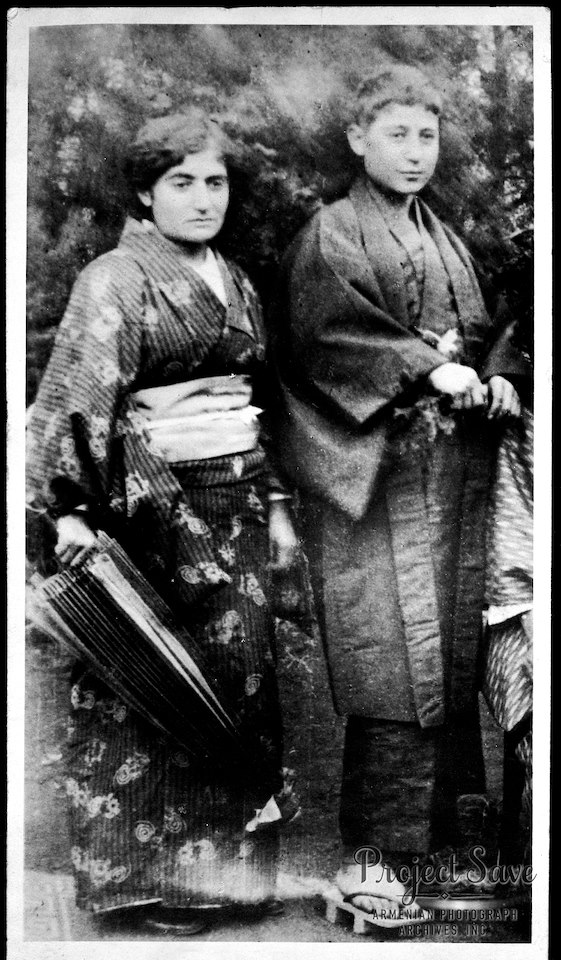

3. It’s 1918 in Tokyo, Japan. A sister and brother are 5,035 miles away from their home in Van–a home and family no longer there. After escaping from the Genocide, they’ve clung to each other for dear life, somehow stumbling east through Siberia and Manchuria before finding themselves in Tokyo, where they decide to pose for a photo in traditional Japanese garb. Why? Perhaps they’re trying to make sense of a world that isn’t recognizable anymore. Perhaps they need proof that they’re still real and alive. They stare awkwardly past the camera as if to say, We can’t believe any of this this either, and we are scared.

Before the trivialization of photography in the digital age, it was often a ritual of wonderment. The camera was a cutting-edge miracle of modernity. It took time to set up and take one photograph. Nothing was taken for granted, from how the subjects were dressed, to the backdrop, to how people were posed. The taking of a photograph was an event. And the physical photo itself then could be an object of comfort or elucidation, giving people pummeled by massive changes something to hold onto and say, That was us, we were there, and maybe our story matters.

For Satenig and Ardashes Megerdichian, their story progressed from Tokyo to Seattle and finally to Boston. And that photograph traveled with them as a living relic, to remind them of what was, what wasn’t and what could have been.

They are gone now, but that photograph lives on at Project SAVE, which means Satenig and Ardashes live on. The survivors of the Genocide and thousands of Armenian immigrants before that and after that are gone, so it’s even more valuable and impactful that they continue to exist in the tens of thousands of photographs in Project SAVE’s collections. They and their stories would be forgotten without the immense photographic evidence painstakingly gathered and cared for in this one organization.

4. I had never known about Vasken and Berjouhie Ekizian. They were siblings who lived somewhere in the Ottoman Empire with their family. Luckily, their parents could afford to have a portrait taken. So there’s a striking photo from 1910 with little Vasken and Berjouhie dressed beautifully, each one holding a toy in their hands. The photographer thought to stand Berjouhie on a chair to be at the same height as her brother. She places her tiny hand lovingly and confidently on her brother’s shoulder. They look at the camera. Both will be killed in the Genocide a few years later.

But because the photograph survived and is now at Project SAVE, their spirits and relevance can stay alive. We know they existed, mattered, and were part of a vibrant, extensive and historic Armenian community in historic Armenia (much of present day Turkey) because of this one photograph. Imagine if it too did not exist.

Like the Ekizians, the stories from before, during and right after the Armenian Genocide are often fragmented and difficult to piece together into a cohesive narrative, and for good reason. Moving pictures, photographic technology and audio recording were not as ubiquitous as they became by the time of the Holocaust. And the geo-political position of the Ottoman Empire in relation to other world powers, especially in the near apocalyptic chaos of World War I, made it difficult for the Genocide to gain the focus it deserved. There’s also the still stunning fact that the word genocide did not exist at the time (it didn’t exist until Raphael Lemkin coined it in 1944).

So, beyond the catastrophe unleashed on Ottoman Armenians at a time when there wasn’t the technology to more extensively document it nor the geopolitical will to stop it, there was also no way to talk about it because it was an event that hadn’t been experienced before quite in that manner and on that scale. Consequently, the diaspora has been collectively stuck in the ripple effect of that trauma. And at times, this has negatively impacted the diaspora’s ability to plan and think about a future that’s more imaginative, free of victimhood and centered on where it lives rather than a romanticized faraway country that has its own government, citizens, interests and realities.

Photographs can be a grounding force that helps recalibrate one’s perspective. Even when we initially don’t recognize the people in photographs, we recognize ourselves somehow. It’s a familiarity and sense of connection that only photographs can ignite. Strangers become familiar and the past seeps into the present so that we can better understand who we are, where we are and what we want to happen next.

5. It’s the 1920s. Three teenagers become friends in an orphanage in Torino, Italy. The orphanage is run by the Mekhitarists (another important but fragile diasporan entity). Their villages decimated and their families gone, the orphans become one another’s family. Somehow, it’s luckily decided by the administrators to have photographs taken. For whatever reason, these three friends are chosen as the subjects. They’re dressed in crisp white shirts and their hair is shiny and combed. Without knowing the context, one might think they’re the usual close school friends and not orphans who’ve survived a massive historical trauma. The girl in the middle leans her head gently towards the one on the left. They both give a look that’s almost typical of a teenager, aloof and cool (or trying to be). The girl on the right clasps her hands on the middle one’s shoulder and rests her head while smiling at the camera. She has a watch or bracelet on her delicate wrist.

We don’t know their names or where they ended up after this photograph. But because this photograph is safe and sound at Project SAVE, we know that they existed. We can preserve and share their part in the broader, diverse story of that period.

The years right after the Genocide were profoundly bittersweet. Those who survived had to pick up the pieces and continue somehow. And part of being able to survive is finding a way to have hope again. It was those people who laid the foundations for the dynamic and vibrant communities in the diaspora around the world. People like Garabed Zakarian and Nevart Chalikian, Genocide survivors who found themselves on a beach in the United States around fifteen years after losing everything. They sit for a photograph with poise and warmth, two broken people transforming themselves into Americans.

Most of the people in the photographs at Project SAVE are in the process of becoming. In addition to being Armenian, they are becoming Syrian, French, American, Egyptian, Argentinian, Canadian, Lebanese, Greek, Polish, British, Cuban, Bulgarian–they are becoming a part of the fabric of their new home countries. In this way, the immense photographic archive at Project SAVE is also a unique visual record of the countless countries that Armenians have called home, where they reclaimed hope.

6. Over one hundred years after the Genocide, there are forces yet again that want to erase or lie about the existence of Armenians. Project SAVE continues to make sure they don’t succeed. For nearly 50 years, it has cataloged over 80,000 photographs that provide direct and clear evidence of the rich and expansive culture and history of Armenians over the past 160 years. But there needs to be renewed investment so that organizations like Project SAVE can grow into their true potential to have more sustainable and long-term impact on a larger scale; otherwise we’re just talking to ourselves and preaching to the choir.

Three teenagers in Torino look out at us from the past. Small children and elderly parents in Yerzinga look out at us. Brothers and sisters, friends and strangers look out at us. They look at us from Tokyo, the United States, the Ottoman Empire, from everywhere Armenians have had vibrant, complicated, sad, beautiful lives, no matter how short or long. They all live on at Project SAVE Photograph Archives. They look out at us from photographs and ask, What’s the plan to reimagine, rejuvenate and properly invest in diaspora organizations that we helped build and that have given so much to the Armenian community and beyond?

Organizations like Project SAVE will not exist forever without larger investments and connecting to the wider world. Those who came before us did their best to create vibrant communities even though they could have easily folded under the weight of grief and the struggles of immigrant life. Many of them now exist in the photographs at Project SAVE. They are witnesses to what was and what is. What happens next is up to you and me.

Thank you for sharing.