EU’s new observer mission in Armenia: What next?

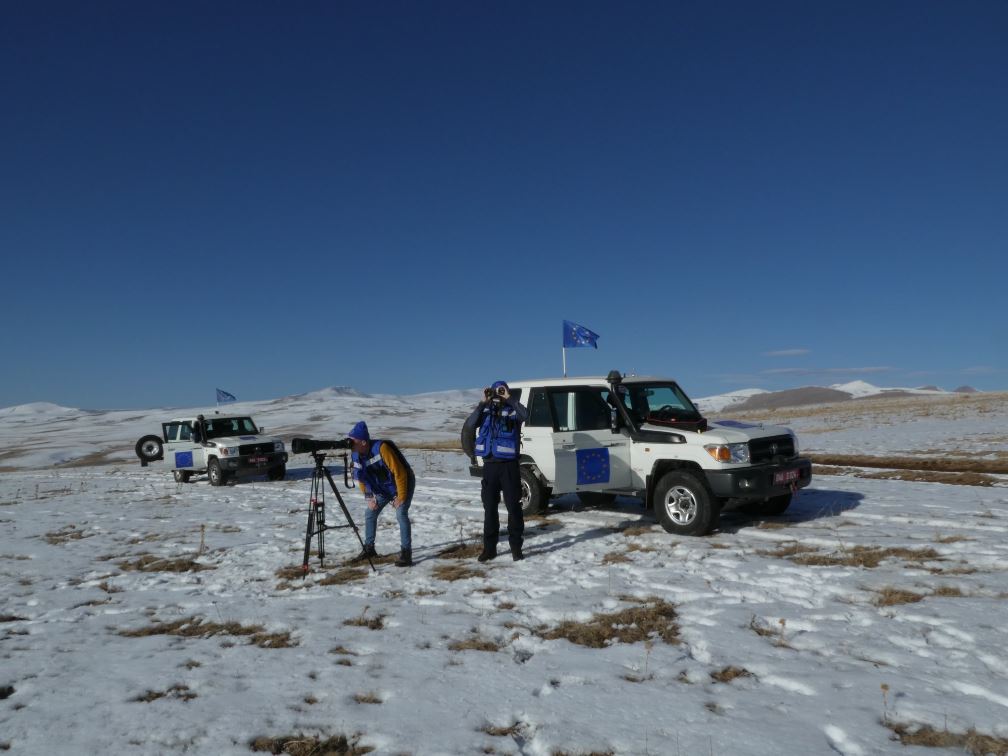

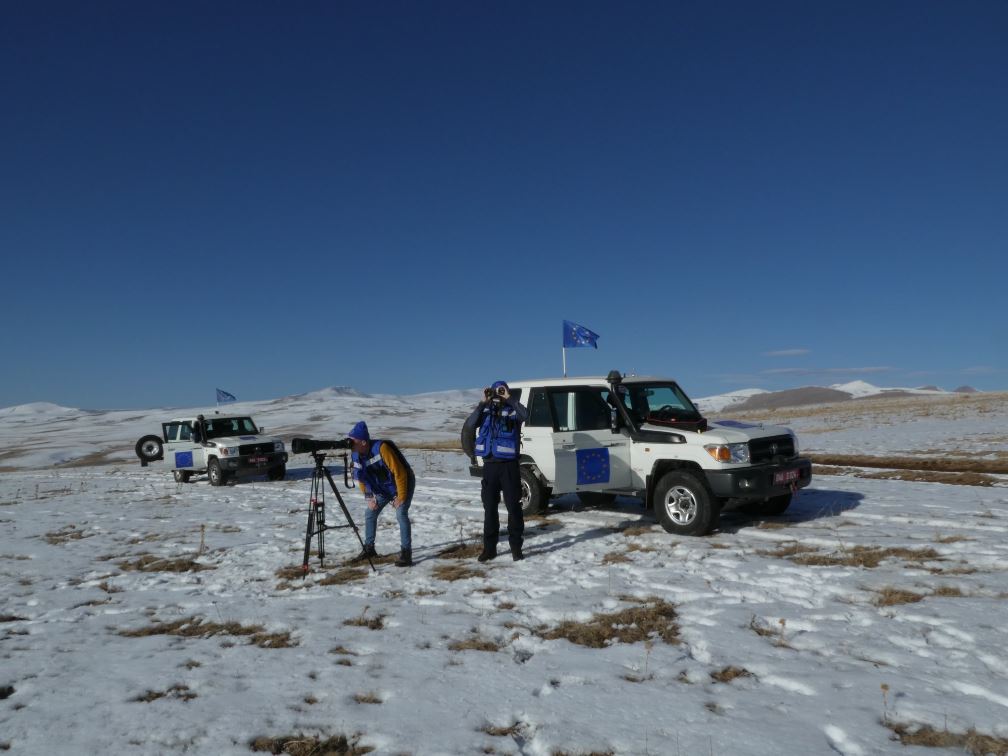

On January 23, 2023, the Council of the European Union agreed to establish a civilian European Union Mission in Armenia (EUMA) under the Common Security and Defense Policy. The mission’s objective is to contribute to stability in the border areas of Armenia, build confidence on the ground, and ensure an environment conducive to normalization efforts between Armenia and Azerbaijan supported by the EU. EUMA will have an initial mandate of two years, and its operational headquarters will be in Armenia. The first EU mission was deployed in Armenia in late October 2022 for two months. On December 19, 2022, the mission left Armenia, but discussions were underway for the deployment of a new, longer and larger mission.

Armenia started to discuss the possibility of deploying an EU observer mission to Armenia immediately after the September 13-14, 2022 aggression by Azerbaijan against Armenia. The scale and scope of aggression, and the lack of action by Russia and the CSTO, triggered a new wave of anti-Russian sentiments in Armenia and pushed forward a quest for additional security guarantees which might deter further Azerbaijani aggressions. In this context, Armenia perceived the deployment of the EU mission as a possibility to stabilize the situation and as a tangible tool of deterrence.

The EU’s active involvement in the Armenia–Azerbaijan negotiations process with the participation of European Council president Charles Michel brought the EU closer to the region. Armenian and Azerbaijani leaders held four summits in Brussels in December 2021, April, May and August 2022. The September 2022 Azerbaijani aggression against Armenia seemed to accelerate the negotiation process, as the United States also jumped in. After weeks of intensive negotiations, the leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan, Michel and French President Emmanuel Macron met in Prague. They endorsed a Prague statement, which, among several things, also envisaged the deployment of the two-month-long initial EU observer mission in Armenia.

Meanwhile, it should be emphasized that from the EU perspective, the mission’s core task was not to deter possible new Azerbaijani aggression but to support the EU-facilitated peace process between Armenia and Azerbaijan. In recent months, the negotiations were stalled. Azerbaijan rejected Armenia’s vision to continue negotiations in Brussels with a 2+2 formula (Michel, Macron, Aliyev and Pashinyan), canceling the new meeting scheduled on December 7, 2022. Simultaneously, Azerbaijan increased its pressure on Nagorno Karabakh and Armenia, imposing an ongoing blockade on the Lachin Corridor on December 12, 2022 and creating an acute humanitarian crisis. In the face of Azerbaijani actions, Armenia decided not to participate in the trilateral Armenia–Russia–Azerbaijan meeting at the foreign ministers’ level scheduled for December 23, 2022.

Meanwhile, Russia came up with an idea to send the CSTO observer mission to the Armenia–Azerbaijan border. The issue was discussed during the CSTO summit, which took place in Yerevan on November 23, 2022. However, Armenia rejected this offer, demanding from the CSTO a clear condemnation of Azerbaijani aggression against Armenia. From Yerevan’s point of view, before sending an observer mission to Armenia, CSTO should provide a clear political assessment of Azerbaijani actions. Armenia’s decision to reject the CSTO offer to send an observer mission to Armenia while working with the EU to deploy a new mission in Armenia triggered some backlash in Russia. Amidst the ongoing Russia–West confrontation due to the war in Ukraine, the issue of what mission should be deployed in Armenia started to be viewed via geopolitical lenses in the context of the West’s efforts to decrease the Russian role and influence in the South Caucasus. As the Lachin blockade continues for more than 50 days with a shortage in electricity supplies and restricted gas flow from Armenia to Nagorno Karabakh, Russia’s inability to force Azerbaijan to stop the blockade has further tarnished its image in Armenia. The criticism toward Russian peacekeepers by high-level Armenian officials has only increased this trend.

On January 26, Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a statement on the EU’s new observer mission in Armenia, criticizing the EU for its efforts to push Russia out of the South Caucasus and arguing that the new mission would only add geopolitical tensions in the region. However, Russia is currently interested in stability along the Armenia–Azerbaijan border, as any new Azerbaijani attacks against Armenia will put Russia in an awkward position. Lack of action in the case of new Azerbaijani attacks against Armenia or Nagorno Karabakh will further tarnish Russia’s image in Armenia. In contrast, any action may trigger a crisis in Russia–Turkey relations with far-reaching implications. In this context, deploying the EU mission also accommodates Russia’s interests, as it decreases the possibility of a new Azerbaijani attack against Armenia. Russia may have concerns that, in the long–term, the growing EU presence in Armenia may threaten Russia’s positions. The launch of recent Armenia–EU political and security dialogue may increase Russia’s concerns. However, at least from a short-term perspective, Russia does not have serious reasons to view the new EU mission in Armenia as a threat to its national interests.

However, Armenia should not make the mistake of thinking that deploying the new EU mission excludes the possibility of new Azerbaijani aggression and opens the way for freezing the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict for years, if not for decades, without any negotiation process. Azerbaijan has made it very clear that it will not allow the establishment of the new frozen conflict. In the absence of negotiations, the likelihood of new Azerbaijani aggression is relatively high, and even the presence of the EU mission will not prevent this. Armenia should take all necessary steps to restart the negotiation process with Azerbaijan. One realistic option is to reinvigorate the Brussels format, and Yerevan should take all necessary steps to reach this goal, dropping any demands which may create obstacles on that path.

Your conclusion to negotiate from weakness will only bring armenia to cede more and more territory and ultimately its sovereignty. The only realistic option is to start digging in everywhere and prepare to defend your homeland. That means underground. Short of standing your ground it is unrealistic to expect azerbajian to stop its offensive actions. It is also unrealistic to expect the west or Russia to protect Armenia if Armenia will not go so itself. Of course Armenia should be actively seeking security assistance from everywhere it can. But inspectors and monitors will not provide any security.