As a veteran of the Artsakh War, I recently marched in New York’s Veterans Parade on November 11. I walked alongside the Veterans For Peace, a contingent of American veterans whose mission is to increase public awareness about the true cost of war, and condemn wars which are not waged out of self defense. I walked because I hoped to raise awareness of the Artsakh struggle for freedom. I had previously met an Armenian-American soldier who had never heard of the Artsakh Army, and I wondered how many more people like him there might be.

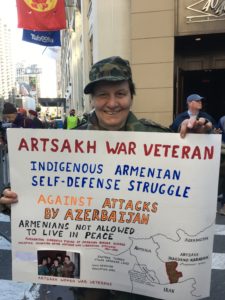

I had made a sign with a map of Artsakh which stated that indigenous Armenians were engaged in an ongoing self-defense struggle against attacks from Azerbaijan, to counteract the false notion that this is just an ethnic conflict. When we got to the red carpet where the U.S. military brass saluted each group, the Veterans for Peace knelt down with their fingers in a peace sign. I also want peace, but the nonviolent ideas of Gandhi and Martin Luther King don’t always work when you are a small nation under attack from an overpowering, violent enemy.

I’m an American woman born in California, so for many, it’s hard to believe I joined the war effort in Artsakh in the nineties.

My journey to becoming a soldier was preceded by a great deal of activism. I attended University of California-Berkeley at a time when there was a strong anti-military, anti-Vietnam War movement. I never imagined myself becoming a soldier. But it was also a time in which many groups of people of color were developing more radical, militant sects of activism, confronting the historic injustices of their respective communities: African-Americans had the Black Panthers and Malcolm X; Native Americans had the American Indian Movement and Leonard Peltier; Puerto Rican-Americans had Lolita Lebron; and for Armenian-Americans, there was the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASLA) and Monte Melkonian.

In 1978, after I had already graduated, Melkonian, who had also attended Berkeley, helped organize an exhibit on the Armenian Genocide in the school’s library. The Turkish Consulate in San Francisco complained, and the exhibit was taken down. Outraged, I joined the Berkeley Armenian Students Association and set up a table displaying photographs of the Armenian Genocide in Sproul Plaza, a popular location in the middle of campus where demonstrations often take place. At one point, a student came by and asked how we made these fake photographs. I was flabbergasted and angry. I made a thousand Xerox copies of a collage of the photos and plastered them all over the city of Berkeley.

That was the beginning of my activism. Later, I would give talks about the Genocide, interview survivors and put their stories on the radio.

In 1988, the earthquake happened in Armenia. I remember I was in bed, and turned on the TV to find Armenia in ruins. It was the first time I had seen Armenia on the national news. I decided I needed to go and do art therapy with the youngest victims. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to acquire a visa (as it was very strict at that time) until three years later. At one point, I was staying in a hostel in Yerevan. There, I met Monte Melkonian, who by then, was a commander in Artsakh, as the war was well underway.

During our conversation, I mentioned I was involved in multimedia, and he asked if I could videotape his soldiers. They were lacking decent footwear and equipment; he hoped to send footage of their conditions to France to convince people to offer aid. For years, I had supported the freedom struggles of other groups. Finally, here was the opportunity to help Armenians in our struggle for freedom. I couldn’t refuse.

At the visa office, a man warned me not to go with Monte because there were those who wanted him dead. He told me I might be in the line of fire. I went anyway.

I was under constant suspicion because who could believe I came here on my own when so many were trying to leave.

When the helicopter landed in Martuni, Armenian children rushed to us. Some of them looked at me, confused, and asked bluntly if I was a boy or a girl. When I told them, they asked how I was able to get permission from my parents to come here on my own. My gender did not make things easy for me. I later found out the other soldiers were upset with my presence, because they couldn’t walk around in their underwear.

One night during tremendous commotion, I asked the soldiers, “Is tonight the battle?” They lied and told me, “No, go back to sleep.” Then Monte appeared and told us to get ready to go. A truck took us to a dark hillside where we all jumped out. The other soldiers ran ahead. But I was carrying heavy camera equipment, and it would be impossible to keep up. I knew they were testing me, but I didn’t give up; I walked in the dark on my own to the hilltop overlooking the battle, where everyone was camping out.

When dawn broke, I started filming. The soldiers told me the battle was over, and it would be okay to go down to the battlefield—so I did. But the soldiers down there were not of Monte’s battalion. They didn’t recognize me and thought I was an Azeri spy. Monte himself had to come and reprimand the soldiers for attacking me. He told them I was Armenian, and that I was working with him.

During the war, I was fortunate to meet the best of our nation, like Arkady Ter Tadevosyan, a top commander who was very humble and gentle and accepted me as a soldier. I was taught how to load and use an avtomat, an automatic rifle (though I never ended up using one on the battlefield). Each time I went to the front lines in battles like Khojaly, Shushi, Fizuli, Hadrout and Aghdam, I dedicated myself to documenting our struggles and victories. I did whatever I could to help. One time, a soldier’s truck ran off the road into a lake; I was asked to dive underwater to help try to find the dead bodies. Another time, after a three-day battle without sleep, Monte asked me to accompany a tank driver to keep him awake. After he nodded off, I drove the tank. I thought of my time back In America when I had volunteered in various women’s prisons in California for over six years. That’s when I learned how to do acupressure because it helped relieve the stress and headaches of the inmates. I offered this service to the soldiers of Artsakh.

I was under constant suspicion because who could believe I came here on my own when so many were trying to leave. I remember meeting Zhanna Galstyan, a famous Artsakh actress who was very active in the war movement, who at one point gave me a hug to show the other soldiers that I was safe. I remember being in a jeep with her son, a physician, on the way to the helipad when Russian soldiers jumped out of the forest, confiscated our jeep, and took us to their headquarters. Like many things that happened in the war, I didn’t know why. They interrogated me, but fortunately, Zhanna came and rescued us.

It was empowering to be part of a nationwide self-defense effort. Whole villages were preparing fortifications. A woman donated all her jewelry for the war effort. I saw an old man carrying artillery shells to the battlefront on his donkey. I thought I had gone there to help, but in reality, all the inclusive, hospitable people I met helped me including Jasmine Gregorian, an English teacher who I call a voski hoki, a golden soul. She bemoaned the fact that before the war her students were talking about books and culture and now it was American cars and films. I made an English-Armenian banner with the Martuni students asking for help. We got in a photo with all the students holding it before the school was shelled.

But not everyone I met was kind like Jasmine. In Martuni, a French-Armenian journalist, Leo Nikolian, who had been following me, put his hand over my mouth, sprayed mace in my eyes, and started beating me to steal my video camera, while his friend stood there and said, “Let this be a lesson to you. This is a man’s world.” Nikolian told everyone I was a spy, but thankfully, I had the support of Archbishop Mesrob Ashjian, a beloved church and community leader based in New York, who wrote a letter to Artsakh military authorities, confirming I was a patriot and clearing my name. As a woman, I wasn’t only fighting against the Azeris, but for the very right to be a soldier. Later, Nikolian was arrested for killing two women in Yerevan with a grenade.

As a woman, I wasn’t only fighting against the Azeris, but for the very right to be a soldier.

The war ended in 1994, but I stayed in the village of Martakert for another six years, giving acupressure with nurse soldiers at the military base. I also taught art and painted, but living there had its trials. I was often targeted for standing up against corruption and violence against women. (It was so good to see that after the Velvet Revolution that some of those same corrupt leaders were exposed and their stolen goods, confiscated!) I traveled back and forth between Armenia and the United States several times before officially moving to New York in the early aughts.

During my time in Artsakh, I made two videos: The Children of Artsakh and The Artsakh Freedom Struggle (both are still on VHS). I felt a responsibility to tell the story of the people I met in Artsakh to Americans. I gave talks on the radio and at schools and churches. But the war had also taken a toll on my health. I realized I was having physical issues resulting from the heavy metals in my body from the bombing and mine explosions. Today, I spend a lot of time trying to heal. I’ve seen so much—decapitated bodies, exploded mine victims and the death of many friends. I did not realize until long after that I had developed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Although I had not been physically injured, I came to accept the fact that I was a wounded veteran.

I was fortunate to be with our soldiers, hiding in the forest before the liberation of Shushi. I still re-live the traumas of war and continue to visit an Armenian woman energetic healer to help release the pain and heal. But I still talk about Artsakh at the many political events I go to, and I have many fond memories, like when I leaped from one snow covered rock to another in the middle of night with my fellow soldiers, so that I could reach the top of the mountain and become a part of Armenia’s history.

Bravo Anoush!!! You have

my admiration and respect👍

👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏

She is my hero!

Thats the fidayouhi nationalistic wonderful Armenian women Abris Hazar Abris aghcig Hayots.getsez

Thanks. At a rally for Artsakh across from the UN I asked the organizers to acknowledge myself and another Artsakh war veteran that was present but they didn’t. Our present Artsakh is due to the whole population’s and soldiers past sacrifices.

Cool story.

On behalf of Armenian Patriotism, I give you a big thank you for whatever help you were able to provide in the war effort.

However. In my book, you are still not excused for the other silly, far-left, depressing, out-of-touch-with-reality articles filled with anti-white propaganda and diatribe you posted previously. Somehow, your leftist political position spoiled it all for me, and as a conservative Armenian, I can no longer take you seriously. I suggest you gather your thoughts and emotions, and try to be inclusive in your articles, instead of diving in head first as a radical leftist, alienating a big part of your audience.

Mr. Hagop, why do you call progressive forward looking Democrats radical far leftists?

Am I to call backward thinking ignorant Conservatives right wing radicals?

And what a life you have lived! The rest of us can only wish we were able to do half as much in the history of our people. I’ve met you before and was instantly impressed by your passion for life and right and wrong. You exemplify the characteristics of some of the dynamic Armenian women in are history like the irrepressible SOSSI. You’ve certainly lived a very full and rewarding life, and continue to do so. If we only had 100 more of you we’d be sitting right now in Baku singing Armenian songs.

Thank you for your kind words. My mother had intergenerational trauma and refused to teach me Armenian lanuage or history. She raised me in an assimilated way and put me in a Zionist neighborhood and school where I was the only non jew and called a goya and discriminated against. She would have been happy if I married a Jewish doctor, but after I saw a book in the UCLA library about what in those days was called the “Armenian Massacre” my life changed forever always.

You have a story to tell. Maybe, you should write an autobiography. So much to say. You paid a heavy price for it but you can be really proud of those years.

A modern day Fedayouhi. This is an icredible story of a highly educated courageous Armenian woman.

Thank you for your sacrifices and wish you full recovery and that your wounds are healed. You must be proud of your accomplishments and contributions.

Finally, do continue to write your poems. Do not pay attention to the ” Mr. Hagop”s of this world. You are definitely entitled to your opinions and views. That’s how the diversity of opinion/expressions becomes a strength.

Keep up lady. My hats off to you

Vart Adjemian

Vart Adjemian

Thanks for the encouraging words. Monte respected Armenian women’s equality. Being used to stand up to discrimination, I knew it was important to perservere and not let misogyny deprive me of my rights.

“She raised me in an assimilated way and put me in a Zionist neighborhood and school where I was the only non jew and called a goya and discriminated against”

“I knew it was important to perservere and not let misogyny deprive me of my rights”

“Misogyny”, “Discrimination”, “Toxic Masculinity”, “War Against Women”, etc etc etc.

All anti-male, especially anti-white-male, 100% BULLCRAP coming straight from American mainstream and social media full of radical leftist loons whose aim is to stir “controversy” where none exist. Incidentally Ms Taulian, these are all a prominent part of “Zionist Ideology”.

Also, you have been lied to and indoctrinated with the idea that “the left fights for rights, and the right violates it”. Absolute Rubbish. Just because someone is so-called “right of center” it doesn’t mean they don’t believe in Human Rights. It just means they are more realistic about it. The main difference is, the modern-day “Liberals” are out in orbit and completely detached from reality.

Our Armenian culture has never “discriminated against women”. We just have a conservative culture which has been historically antithetical to the ideas of Western Liberalism that exists today, and with which you are toying with in your writings. In our traditional culture, males and females are distinct and each with abilities and advantages of their own. And that is what has kept our family unit historically bonded and cherished. And there is NOTHING wrong with this, unless of course you are a so-called “Progressive Liberal”. To the Liberal Lunatics of the west, almost everything is “discrimination” and “violation of rights”.

@ Mr Adjemian

Yes, everyone has a right to their opinion, including myself. And the beauty about America is, you also have the right to be wrong in your opinions, as does Ms Taulian.