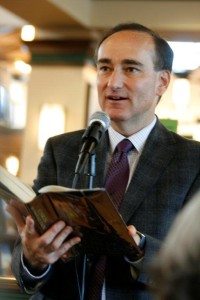

Chris Bohjalian is the kind of author who grabs you by the heart and refuses to let go. How he can manipulate several plots simultaneously, travel cross country promoting his work, raise a family, and enjoy a private life calls for a supreme juggling act.

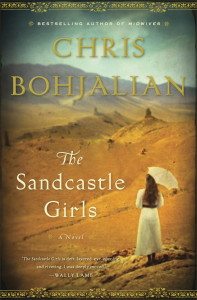

Of the 15 books he has written, his latest—The Sandcastle Girls—could very well be his best. If not the ultimate, at least the most ambitious and personal novel in a career that’s spanned over 25 years.

The novel is a sweeping saga set in the cauldron of the First World War, a tale of love and loss, and a family secret that’s been buried for generations.

The book enhances Bohjalian’s stature in the world of American literature and makes it a “must read” for anyone in search of adventure.

One of his first novels, Midwives, was a Number 1 New York Times best seller. Bohjalian’s work has been translated into more than 25 languages and 3 have been made into movies. He lives in Vermont with his wife and daughter.

The Sandcastle Girls is dedicated to the memory of his mother-in-law Sondra Blewer (1931-2011) and his father Aram Bohjalian (1928-2011).

“Sondra urged me to write this novel and my father helped to inspire it,” he notes.

A question-and-answer session with the author follows.

Tom Vartabedian: What prompted you to write The Sandcastle Girls?

Chris Bohjalian: I’ve been contemplating a novel about the genocide for most of my adult life. I tried writing one in the early 1990’s between Water Witches and Midwives. But it was a train wreck of a book. If I’m going to be kind, I might simply call it “apprentice” work. But “amateurish” would be fitting, too. (Scholars and masochists can read the manuscript in my alma mater’s archives.)

A few years ago, my Armenian father grew ill. And as we visited, we poured over family photos together and I pressed him for details about his parents, who were survivors from Western Turkey. I also asked him for stories from his childhood. After all, he was the son of immigrants who spoke a language that can only be called exotic in Westchester County during the 1930s.

Finally, a good friend of mine who is a journalist and genocide scholar urged me to try once again to write a novel about what is, clearly, the most important part of my family’s history. So I did. And this time, it all came together.

TV: How long did it take you to write?

CB: I started the novel in the summer of 2010 and finished it in the fall of 2011.

TV: Was the story factual or fictional—or a cross between the two?

CB: Oh, it’s a novel. Absolutely. Nevertheless, my narrator Laura Petrosian is a fictional version of me. Her grandparents’ house was my grandparents’ house. But Elizabeth Endicott and Armen Petrosian were not my grandparents. I hope the history is authentic. I did my homework. I hope my characters’ stories are grounded in the particular ring of Dante’s Inferno that was the Armenian Genocide. I hope I have accurately rendered that moment in time.

TV: Any Turkish resistance to the book?

CB: Not yet.

TV: Any chance of this being promoted to television or Hollywood?

CB: One can always hope. If you know any producers, let me know.

TV: How has it been received by the Armenian reading public?

CB: Early reactions have been very encouraging. And here, I think, is the reason why.

A few years ago, I heard the incredibly inspiring Gerda Weissmann Klein speak at the University of Texas Hillel. Gerda is a Holocaust survivor and author of (among other books) All But My Life. Someone asked her, “What do you say to people who deny the Holocaust?”

She shrugged and said simply, “I tell them to ask Germany what happened. Germany doesn’t deny it.”

As Armenians, we have a genocide in which 1.5 million people were killed—fully three-quarters of the Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire—and yet it remains (to quote my narrator in The Sandcastle Girls) “the slaughter you know nothing about.” It is largely unrecognized.

And so when Armenians have read advance copies of the novel, they have been deeply appreciative of the story and the way it tells our people’s history.

My point? We are hungry for novels that tell our story, that tell the world what our ancestors endured a century ago.

TV: How has the book benefitted you in terms of promoting your own heritage and culture?

CB: It has helped me to understand more about who I am—the geography of my own soul.

TV: How does this relate to your other works?

CB: Pure and simple, the best book I will ever write—and the most important. I know this in my heart.

TV: During its conception, was there any connection made with notable Armenian historians and writers like Peter Balakian?

CB: The epigraph is from one of my favorite Balakian poems. And Khatchig Mouradian (The Armenian Weekly editor and genocide scholar) was more generous with his time than you can imagine. I learned so much from him. And I still do, even though the novel is finished.

TV: Who might your favorite Armenian writer be?

CB: I am deeply appreciative of the work rendered by Nancy Kricorian, Mark Mustian, Carol Edgarian, Peter Balakian, Micheline Aharonian, William Saroyan, and Eric Bogosian. Pick one? Not a chance!

TV: Whatever happened to the first genocide book you wrote 20 years ago?

CB: It exists only as a rough draft in the underground archives of my alma mater. It will never be published, even after my death. I spent over two years struggling mightily to complete a draft and I never shared it with my editor. The manuscript should either be buried or burned. I couldn’t bring myself to do either. But neither did I ever want the pages to see the light of day.

TV: Collectively, as a diaspora, what can be done to observe the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide in 2015?

CB: Well, recognition by the Turkish government would certainly be nice. It would also be encouraging to see a sitting American president acknowledge what happened and use that dreaded “G-word.” Seriously, what does “realpolitik” get us with this issue? Regardless, I expect poignant and powerful observances around the world.

TV: Living in rural Vermont, do you feel isolated from the Armenian community? How has it impacted your heritage and that of your family?

CB: I love Vermont, I really do. But I think the fact I live in Vermont was one of the reasons why my visit to Beirut’s Armenian quarter and Yerevan was so meaningful this spring.

I try to remind myself of something I saw written as part of a Musa Dagh mural on a column in Anjar, Lebanon, where the survivors of Musa Dagh were resettled: “Let them come again. We are still the mountain.”

The reality of the Armenian Diaspora is that 70 percent of Armenians don’t live in our homeland. And yet, somehow, we have retained a national identity.

I think that whoever wrote, “We are still the mountain,” wanted the sentence to be interpreted two ways. Certainly, he meant Musa Dagh: Attack again if you want, we are still those warriors. But he also meant Ararat. Even here in Lebanon, we are still Armenians.

And so for me, even though I am in Vermont, I am still a part of that mountain.

TV: What are your impressions of Armenia?

CB: I was so happy there this spring. My hotel was on Abovyan Street and it intersected with Aram Street two blocks away. Well, Abovyan was the first modern Armenian novelist and Aram was my father’s name. He passed away last year and his death made my journey to Armenia all the more important to me. To see his name intersecting with a great Armenian novelist was a wondrous and unexpected blessing—a gift!

Obviously, like many post-Soviet nations, Armenia has a lot of monumental economic hurdles. And those hurdles are exacerbated by its place in the Caucasus region. But, my Lord, is it beautiful! I have never been better cared for and felt less like a stranger in a strange land.

TV: Will there be a sequel to The Sandcastle Girls or another work related to Armenian literature?

CB: I don’t know if there will be a sequel. I have never written a sequel. But there will be more Armenian or Armenian American-set fiction. That’s very, very likely.

Pre-order The Sandcastle Girls here. Follow Chris Bohjalian on Facebook and Twitter.

We are proud of Chris

And we will be always proud

Being Half-Armenian and

Caring for Armenians and their genocide…

The cover of the book is so beautiful and melancholic

That when i look at it…

I feel my self …

As if …I’m there with my beloveds…in Der-Zor desert

Standing…on a hill… full of skeletons under my feet

Imaging smashed eyeballs still wet with tears

And i can feel and see their genocided hands pointing to sky

Calling saints…calling Jesus …calling mercyful God

Singing ‘Sharagans’ (hymns) of Gomidas

Can Chris’s book, which carries name of Christ answer why…!!!

(c) Sylva-MD-Poetry

Bravo… May God give you strength and more ideas to write more books about our people and hope that the current book turns into a movie…

Gayane

Fluid Dynamics

Five moves in five years.

I started to feel/wish l was a huge boulder;

unwilling to budge anymore.

But when the time came, I did…

A chip off the mountain,

both stationary and fluid,

I am still the mountain.

Our mystical mountain is also a river,

branching off into streams that carry us far away,

and become tributaries to other mountains,

other rivers, in other lands.

Yet, the ebb and flow,

which is our nature,

is grounded by our mountain.

Perhaps physics can teach us.

how the inert rediscovers its momentum,

how the undead find life again.

Or how the dead find their rest.

(c) 7-5-2012

When will Sandcastle Girls be translated into Russian, and can I pre-order it? I very much want to read it and then let friends and family know about the book in Yerevan.

Loved Sand Castle Girls. I’m 100% Armenian, and my grandparents families were in the genoicde, My grandmother’s stories were not detailed, but Sand Castle Girls nails it.

As some one who has done some writing, I understand not wanting to show certain things to the general public thinking it’s not refined enough, but please tell me why you won’t publish your first genocide book?

Why can’t we see it? I’ll bet it’s important.