Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin trotted down the steps of Tel Aviv’s City Hall one November evening in 1995 when a gunman discharged three rounds from a concealed Beretta 84F. The PM had just concluded a rousing speech at a peace rally in support for the Oslo Accords, which he had begrudgingly signed along with an equally apprehensive Yasser Arafat less than six weeks earlier. The nearby Kings of Israel Square (now Rabin Square) was still teeming with people when Rabin collapsed onto the ground, just feet away from his car. Forty minutes later, he would be pronounced dead. From his pocket, the doctors pulled out a blood-soaked sheet of paper inscribed with the lyrics of the popular Israeli song “Shir LaShalom” (Song for Peace).

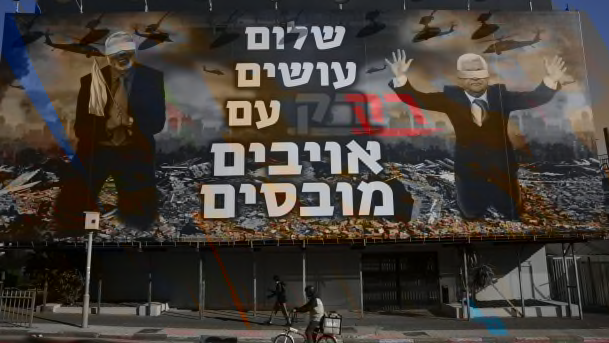

His assassin, the radical-Zionist Yigal Amir, was immediately apprehended while still grasping the murder weapon. He later told investigators that he had acted on “the orders of God.” In the weeks preceding the murder, religious conservatives brandishing posters depicting Rabin in a Nazi SS uniform, and Zionist hardliners chanting “Rabin is a traitor” marched in a series of rallies across the country led by a certain Benjamin Netanyahu. Opponents of the Oslo Accords denounced the peace plan as a capitulation to Israel’s enemies, and the Israel Defense Forces’ unilateral withdrawal from “occupied territories” a heresy which denied the Jewish people’s “right to biblical lands.” In court, the deeply religious Amir later testified, “I acted according to din rodef.”(a death sentence issued under rabbinic law)

A much younger Rabin had been known for his uncompromising stance on Zionism. In the lead-up to the 1948 Israeli-Arab War, he had led commando raids against Mandate Palestine’s British administrators and local Arabs alike, the latter of which he expelled en masse from the embryonic Israeli State. He is also widely credited with masterminding the stunning Israeli victory over the combined armies of Egypt, Syria, Jordan and Iraq in 1967.

Two decades later, the man once known among Palestinians as “Rabin the bone breaker” stood with his former nemesis on the White House lawn. “We who have fought against you, the Palestinians, we say to you today, in a loud and a clear voice, enough of blood and tears … enough!” he told Yasser Arafat as he reached over for the historic handshake. Three years later. he was dead.

The cause of Israeli-Arab peace had already claimed its first victim from the political class by then. Fifteen years earlier, Rabin’s predecessor (and successor) Prime Minister Menachem Begin concluded 12 days of secret negotiations with his Egyptian counterpart, President Anwar Sadat at Camp David. With the Geneva negotiations ending in deadlock and self-serving public spectacle, a frustrated Sadat had initiated a series of top-secret overtures to his Israeli counterparts.

Less than four years earlier, he had launched an initially-successful, but ultimately disastrous invasion of the Israeli-occupied Sinai Peninsula. Long dismissed at home as a mere puppet of Egypt’s illustrious late leader Gamal Nasser, the general-turned-autocrat had wagered his fragile legitimacy on his ability to avenge his country’s humiliating defeat in the recent Six Day War. But by the time Israeli armor took up positions less than 60 miles from Cairo, the writing was on the wall: the military solution had failed. Peace was the only option.

In November 1977, Sadat shocked the world when he addressed the Knesset in Tel Aviv, paving the way for Egypt to become the first Arab country to recognize Israel in 1979. As the first Israeli troops began their phased withdrawal from the Sinai, Sadat began to feel the heat both at home and abroad. Egypt was immediately suspended from the Arab League under widespread condemnation across the region. Sadat would spend the rest of his presidency putting down armed uprisings across the country. Two years later, he too would be dead—gunned down by his own officers.

For a fleeting moment following Armenia’s 2018 Velvet Revolution, there was cause to contemplate whether we would witness, in our lifetime, an Azerbaijani president addressing the Zhoghov in Yerevan, or an Armenian Prime Minister declaring “enough of blood and tears” under the gaze of dozens of international new cameras. Many Caucasus-watchers were anxious to hear what kind of fresh ‘out-of-the-box’ ideas the succeeding generation of Armenian policymakers planned to inject into the terminally-stalled Karabakh peace negotiations. Some were encouraged by a ‘novel concept’ floated by a then newly-elected Pashinyan that any peace plan would require the consent of the people of Armenia, Artsakh and Azerbaijan.

It’s tempting to draw parallels between two seemingly unending conflicts propped by a clash of historical narratives, competing victimization (real or imagined) and existential angst fueled by deep reciprocal distrust. On the one hand is a burgeoning democracy with an ancient claim to an isolated bit of land surrounded by petrol-guzzling enemies. On the other is two rival national leaders—one whose domestic legitimacy was forged at the ballot box, the other’s inherited and ratified through the promise of vengeful war—risking their own political lives for the sake of sparing the lives of their own peoples.

If Saturday’s public discussion in Munich demonstrated anything, it’s that Aliyev is no Sadat, while Pashinyan is not yet ready to inherit the right, or the liabilities, evoked by allusions to Rabin. Previous generations of Armenian and Azeri statesmen have traditionally been careful to avoid tipping the delicate balance between acting as sincere negotiators abroad and appearing to be tough hardliners at home. In Munich, both leaders showed a clear preference for the latter.

And that’s where the parallels end. For both Rabin and Sadat, the price of peace (or at least the genuine exploration of it) was deemed to be worth the cost of their political lives—and ultimately their literal lives. Had they only known the “courage” needed to drag their feet into a posh Bavarian hotel meeting room for an awkward photograph.

Stripping away all the incoherent historical diatribes, thinly-veiled chest-thumping, cynical victimization and burden-shifting on display in Munich, the 45-minute long debate was essentially a reiteration of two mutually contradictory expectations of what peace would entail. Armenia hopes negotiations will simply validate the situation that currently exists…of sorts. For Azerbaijan, any basis for negotiations begins and ends on the basis of its absolute insistence on total “territorial integrity”—a dead end. So, we’re left with territorial integrity versus self determination, the exact same negotiation stances proposed 30 years ago.

Meanwhile, the conditions locking the two countries in this perpetual security dilemma—historical memory, identity politics, deep mistrust, dictatorship and corruption—haven’t changed either. The same can be said for the available choice of outcomes: war, perpetual status quo or some sort of negotiated peace. All three options offer pain, compromise and uncertainty.

Going forward, it is important to reiterate certain matters of verifiable certainty: 1-Azerbaijan is a dictatorship, 2-the existential threat of annihilation is absolutely real (the whole “murder-mutilation” phenomenon seems to be one-directional, 3-the local Armenian population’s indigenous status remains without question (no matter how many UNESCO World Heritage sites get bulldozed), and 4-there is no conceivable way in which Artsakh would voluntarily relinquish its hard-fought independence for the vague promise of having its status decided on “at a later time.” They’ve never given us reason to trust them, nor should we have to.

But with all that said and done, we can only go so far in pretending that nothing lies between Ijevan and the Caspian Sea. Eventually people on either side of the trenches will have to find some way to interact. While it’s still true that Azerbaijan’s calls for peace seem hollow when interspersed with calls to ethnically cleanse Yerevan, it’s equally true that Armenia’s own contentment with the status quo offers little more than lip service to the prospect of peace. So far as regular talks continue to be scheduled, the guns stay silent. Still, it’s somewhat astonishing that after 30 years of quiescence, the most creative contribution we can come up with is some variant of, “We would reach out to the Azeri people for dialogue, but whoops, you’re a dictatorship” [shrug shoulders]. Are there truly no other uncharted avenues left to explore?

Of course, we know through the benefit of hindsight that history did not reciprocate Rabin and Sadat’s sacrifices. Whatever hopes for peace that may have existed at Camp David seem hopelessly naive in retrospect, as the status quo looks more entrenched than ever. But there is one area where the parallels with Artsakh don’t quite line up: at least along the Green Line, the regular flow of imaginative if unusual peace proposals continue to garner fresh excitement, hostility, tears, ridicule…and even the odd plagiarism accusation.

Since we can’t have Rabin or Sadat, where is our Jared Kushner?

Excellent insight into a complex problem. It seems that the Armenian side is burdened by the past tacit “agreement” of the Madrid Principles…. one of the most one sided plans against the oppressed victim and victor. I think Pashinyan made an excellent point when he said when considering “territorial integrity” , one has to consider whose territorial integrity has been violated. Azerbaijan’s entire argument is based on Stalin’s “award” of Karabakh as an autonomous region. Whatever that meant ended with the dissolution of the Soviet Union. This is a legal argument that should be pursued.

I read the article with great interest.

I was looking where would Kushner fall in this great illustration.

Kushner, in my modest opinion has no interest with Armenia, nor has the time to read another 20 books to understand the situation.

Jared Kushner is a lightweight. He is no Sadat ror Rabin and it is highly doubtful that he is interested or can play any role in reaching to a resolution on the status of Artsakh.

Raffi’s article is insightful and clarifies the thorny and critical issues related to the conflict.

However, I could not understand the title or the last line.

Vart Adjemian

Hi Vart, the reference was intended to be sardonic. (Click on the URL over Kushner’s name in the last line)

Thanks for your continued readership and insightful comments!

-Raffi