“Two Kinds” by Amy Tan, an excerpt from her novel The Joy Luck Club, encompasses the problematic bond between a Chinese immigrant mother and her American-born daughter, Jing-mei. By focusing on Jing-mei’s story, Tan sheds light on the enduring nature of intergenerational trauma.

The mother’s past, characterized by family loss and the disappointment of her aspirations in China, has shaped her goals for Jing-mei’s success. Jing-mei has to confront her own identity and will when challenged by her mother’s expectations, which trigger her internal struggles and self-doubt. Jing-mei’s rebellion against her mother’s wishes symbolizes the learning process of overcoming the cycle of trauma and creating her own path. This story also shows a glimpse of the mother and daughter understanding each other, leaving the possibility of healing and reconciliation.

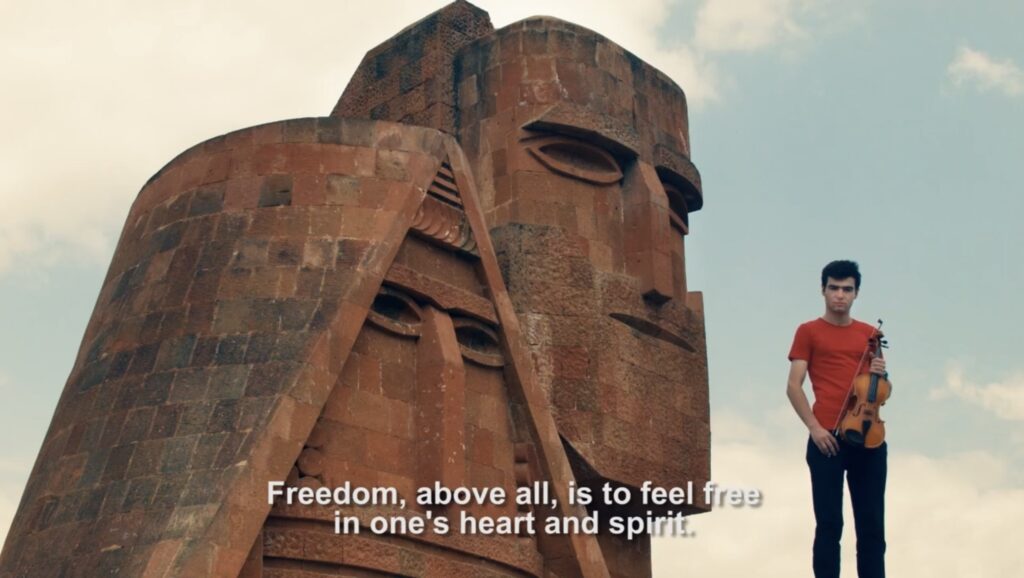

The story made me reflect on my own family. Yet what I am about to illustrate is not only the trauma of immigrants but, in particular, the intergenerational trauma of Genocide survivors. I am incapable of turning a blind eye to my personal experience and did not hesitate to write about it. I am from a simple Armenian family whose stories you have probably heard.

Raids began in the Ottoman capital of Constantinople on April 24, 1915. Over 650 Armenian intellectuals and public figures were arrested and deported. Others were executed in small groups. In the next few days there were another 2,000 victims. The same scenario played out across the Ottoman Empire. It was a new and terrible policy, deporting the Armenian civilian population to the Syrian deserts for “security” reasons. Their true destination was death. (Tehlirian on Trial: Armenia’s Avenger documentary)

Some of my family members escaped to Georgia, and others to Lebanon. Separated and broken, they changed their identities and last names. My great-grandfather, a child on his mother’s back through the death march across the Syrian deserts, recalls how their legs gave out, barely keeping them alive. My grandpa was an artist who dedicated his life and work to the Armenian Genocide cause, painting his father’s memories. I’ve never encountered an Armenian who doesn’t work hard to preserve our culture and prevent it from being lost again.

Last year, my people faced ethnic cleansing by Azerbaijan, which was financially supported by the United States and Israel. 120,000 people were kicked out of their homes, living their lives as refugees once again. It was one of the most difficult beginnings to a school year. I had just started college, studying politics with the hopes of helping my nation, but I wondered if I would be able to contribute. Would my people face the same fate as the Assyrians or the Kurds, as a people without land? That reflection never left my mind.

In August 2023, my grandma and I saw an animated film on the Armenian Genocide in theaters called Aurora’s Sunrise. It was about a 13-year-old girl who fled to the United States and who achieved success in Hollywood while revealing the true colors of the Young Turks. There was not a single point in the film that did not make the audience cry. There were many elderly individuals whose parents had survived the Genocide, including my grandmother. Yet she was happy that it depicted the cruelty of the Genocide in city theaters.

Shame is one of the consequences of growing up in war and genocide. This is one of the impacts of generational trauma. I’d never used my voice to address these concerns previously, because I felt humiliated that my nation and people were shrinking, scattered throughout the globe, losing while attempting to be proud. For a long time, I avoided discussing my origins. I tried forgetting my mother tongue. I considered changing my surname. Many Armenians are still living under foreign identities for their own safety or to avoid disgrace. A large number of people who survived the Genocide faced a problem speaking about it, since they were filled with trauma and fear. This silence is handed down to every generation that follows, creating a hard barrier in addressing the trauma and its outcomes on subsequent generations.

Many of my friends who survived the recent ethnic cleansing spoke up about the refugees’ mental health, breaking with tradition. One of my peers, Nare Arushanyan, is the same age as me, but instead of attending college and furthering her education, she was subjected to a blockade with no food, water and medication. She watched Israeli missiles fly above her head as she was forced to flee her home. “Failing to fulfill my promise to those soldiers and to my homeland weighs heavily on me, causing guilt and a deep sense of uselessness. It’s the one commitment I couldn’t uphold, leading to troubling nightmares and a persistent struggle to accept this devastating reality. This is the feeling that will forever stay with us, and there’s no way to avoid it,” she said in an Instagram post.

If there is no passion and fire for independence and resistance in the people, then it is easier to control them. The oppressor’s primary tactic is to traumatize citizens.

These words of guilt reminded me of an interview with another genocide survivor, Motaz Aziz, the famous Palestinian journalist who evacuated from Gaza. “I keep feeling guilty for it. For the clean water I drink now here. For sitting maybe on a nice couch. No drones above my head trying to kill me. Not seeing human parts after Israeli airstrikes. Not seeing destruction.”

This is how the oppressor succeeds: by destroying the people’s passions and making them feel guilty for enduring such atrocities.

Whether it is Jing-mei’s immigrant mother or my grandparents who survived the Genocide, we bear the fear and shame imposed on us. While Jing-mei strives to meet her mother’s high expectations, I strive to speak about this to a bigger audience and provide something for my people and family.

References

Adrine Babakhanyan, “The Armenian Genocide and The Transgenerational Cultural Trauma” 2019, California State University, Northridge.

Amy Tan, “Two Kinds” February 1989.

Hoyte, Kirsten Dinnall. “Contradiction and Culture: Revisiting Amy Tan’s ‘Two Kinds’ (Again).” Minnesota Review, 2004.

Holocaust Encyclopedia “The Armenian Genocide (1915-16): Overview”

Its so important to address transgenerational trauma that comes with living in genocide…Too many are blind to it. Very powerful, loved this piece!

A beautiful and eloquent expression of deep and complex emotions!

This article masterfully connects Jing-mei’s struggle in Two Kinds with the experiences of Armenian Genocide survivors, highlighting the strong impact of intergenerational trauma. Through her family’s history, the author shows how historical tragedies deeply shape identity, drawing a comparison between Jing-mei’s search for self and her people’s collective memory.Thanks Melian .