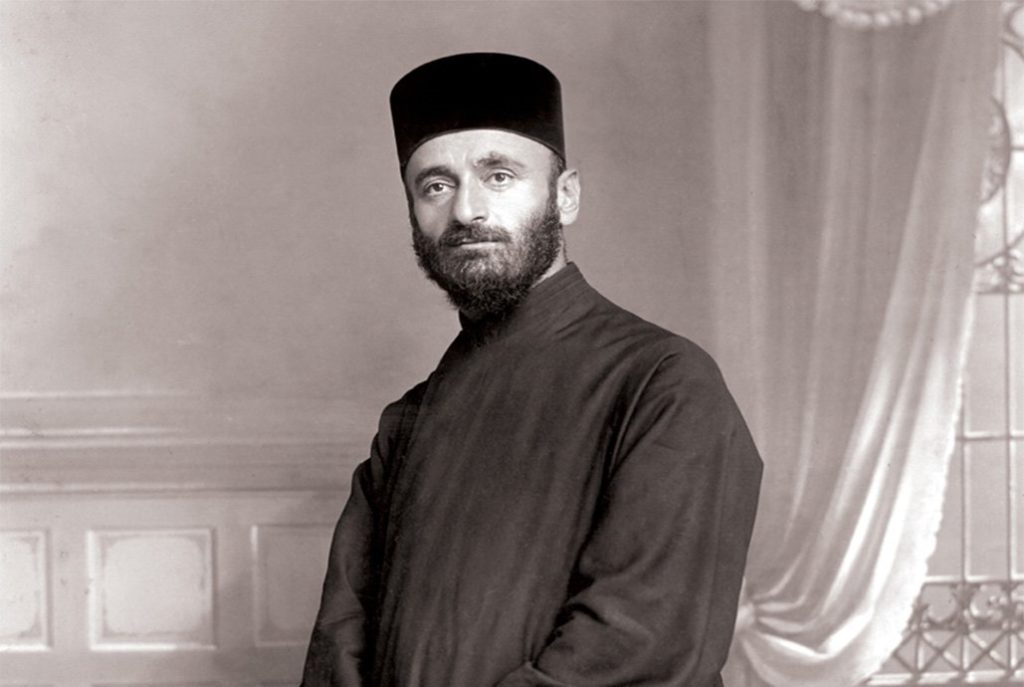

Studying the role and significance of the musical and scientific heritage of classical Armenian musician Komitas Vardapet in the context of national art which marked the era, we have come to the conclusion that in the post-Komitas period, the Armenian composer school in its manifestations was established based on the creative principles and standards of the great classical musician. Komitas’ art is the stronghold from which the national composer school was derived and developed. “Komitas and Armenian art of composing music” became a reference point for composers and musicologists. This interconnection is the cornerstone of almost all Armenian musical works.

In our publications1, we researched Komitas Vardapet’s interactions with foreign composers and artists. We were inclined to refer to famous foreign artists in order to substantiate Vardapet’s activities. Of course, it is important to consider the role and significance of Komitas’ work in the context of world music culture, and we fully share the viewpoints of prominent musicologists. However, it should be noted that a small part of Komitas’ heritage is highly appreciated, whereas Komitas surpassed many artists with his innovative ideas. For example, Komitas’ ideas in musical and aesthetic education were revealed before the musical and pedagogical views of Zoltán Kodály and Carl Orff. Komitas developed a scientific approach to folklore before Béla Bartók. These are separate materials for study.

It is high time we made a new and comprehensive review of Komitas Vardapet’s interactions with Armenian composers. Certainly, it is possible to find common features between creative individuals. However, Komitas’ name is associated with the term school in Armenian composing art, which implies a scientifically coordinated approach.

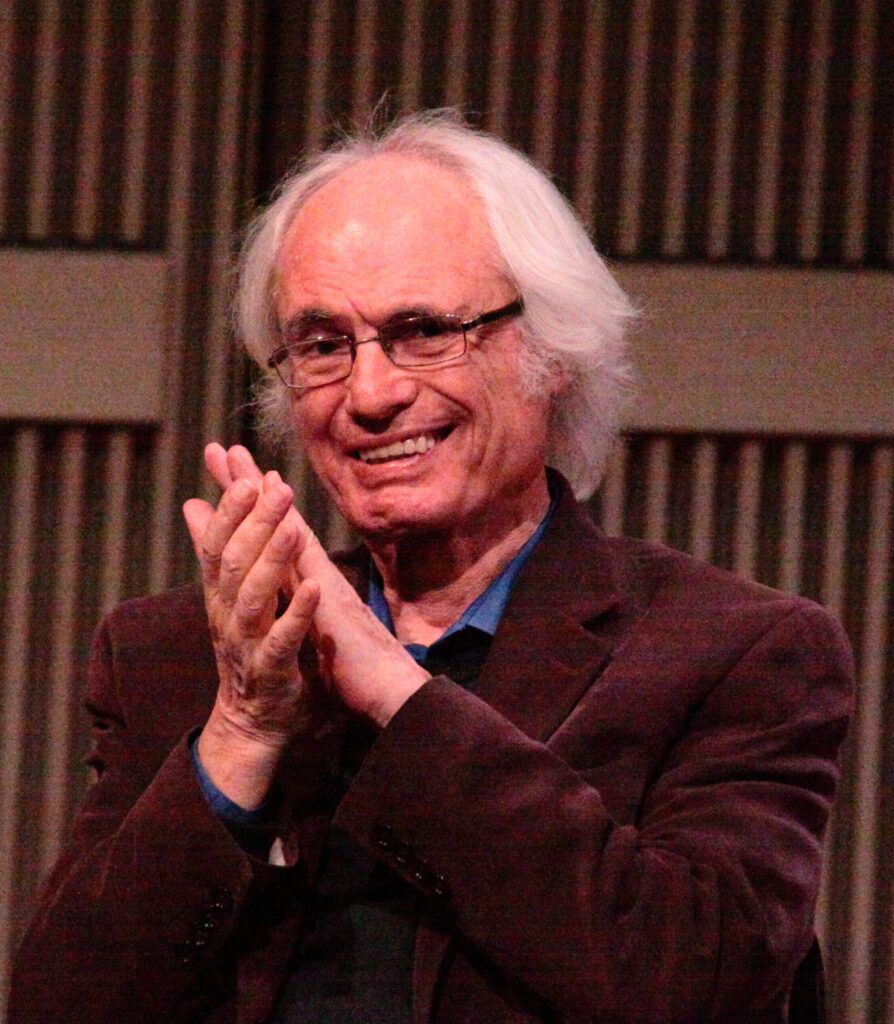

Tigran Mansurian is the greatest representative of the Komitas school in composing art. Mansurian came to know and love the uniqueness of Komitas’ great art from childhood. He was deeply connected to him. “I’ve always tried to look in the direction that Komitas looked,” he said.

Mansurian made his first steps in music by himself without a teacher. “I consider Komitas the only and irreplaceable teacher, my spiritual father and shrine in music,” confessed the composer.

Mansurian has become the successor of Komitas’ ideological, aesthetic and composing-constructive principles. He is one of the first who modernized the traditions of the great classical musician and reasserted Komitas’ messages on a new aesthetic basis. In contemporary music, Mansurian continues to open and uncover the ciphers of Komitas’ art. “I love to acknowledge the value of Komitas’ sounds, their scarcity and significance in his works.”

Komitas noted the perspective of combining Eastern and Western musical cultures. Mansurian’s art is also developing on the Eastern and Western borderline. This is a “crossing point” and a source of inspiration for Mansurian, who is rooted in Komitas’ art, “musical tradition” and “artistic certainty.”

Long ago, Komitas Vardapet presented Armenian song to the world. Today, Mansurian continues this creative mission, while often interpreting the peculiarities of his own works. The composer constantly substantiates his interpretations and the process of crystallization of Armenian music through the art of Komitas Vardapet. Mansurian’s accurate interpretations of Komitas are based on his infinite love for the classical musician and his exclusive knowledge of Komitas’ musical works. Their relationship is presented in the form of the senior and the junior.

A 2014 review referred to the spiritual and stylistic similarities between Komitas and Mansurian: “Mansurian looked back to Komitas, becoming skillful in an unmatched style. He synthesized his cultural roots by means of Avant-garde music, making this synthesis a basis for creativity. Mansurian’s music is modern and eternal. While Komitas is the ‘Alpha,’ Tigran Mansurian is the ‘Omega’ of Armenian music.”

The composer has never endeavored to show the beams of his artistic and scientific thoughts; “Komitas has wonderful articles, which I have read,” confesses Mansurian.

However, the composer “has read” them with insight and analytical coverage typical of his talent. Mansurian’s thoughts, which are compact, informative and condensed, are worthy of Komitas Vardapet. They are perfectly artistic, scientifically substantiated, profound works, which have not lost their relevance. It is impossible to complete the image of Komitas Vardapet without Mansurian’s articles, reviews and introductions, the scientific value of which is a significant contribution to the field of Komitas studies.2 He has dedicated musical compositions and musicological works to Komitas Vardapet.

In 1969, on the occasion of Komitas’ centennial anniversary, Mansurian authored an article titled “For a New Revelation,” viewing Komitas’ style in the context of world music. The issues and theoretical generalizations set forth in this article are still important today in appreciating the historical significance of Komitas Vardapet. In the article, Mansurian covers the most important and topical issues in the field of Komitas studies. Mansurian was the first composer to give Komitas and his art such a brave and well-grounded assessment during that period.

Mansurian’s article was published in the 10th issue of the magazine Soviet Art. In the sixth issue of the same year, 1969, an article by musicologist Gevorg Geodakyan entitled “Komitas’s Style and Twentieth Century Music” was published. 3 Geodakyan, studying Komitas’ musical-stylistic peculiarities, substantially revealed the connection of Komitas Vardapet with the world’s musical art for the first time. Geodakyan’s article has been examined many times as a new scientific study.4 Compositional analyses and perspectives prevail in the valuable theoretical generalizations in Geodakyan’s article.

“Komitas is one of the developers of 20th-century world music trends and principles,” said Mansurian,5 who consistently strives to evaluate Komitas’ style by world and contemporary art standards in the context of European music achievements. He sees the importance of Vardapet’s art among Western European music development trends, innovations and in rank with those who have reached artistic heights. “If he is a representative of the theory of world music of his time, then he is also a guideline to recognize our place in today’s world art, to recognize our nationality in world music,” writes Mansurian.

The composer does not consider Komitas to be a representative of purely national music; he makes Vardapet’s unique description complete together with his “spiritual brothers” – Bartok, Kodály, K. Shimanovsky, M. de Falla and I. Stravinsky. Mansurian puts aside Komitas-folklorism interaction and highlights the importance of comparative analysis in musicology. The issues raised by Mansurian become a matter of musical discoveries only in our times.6

It is known that Komitas Vardapet was one of the founders of Armenian folklore studies. He refined the rustic song giving it a new, flawless quality. “He put the work of collecting Armenian music onto new, logically intentional, scientific grounds,” writes Robert Atayan.7 Komitas used the folklore sample as part of the ethno-musicological study even before Bartok.

Scientist Nikoghos Tahmizyan writes about Komitas’ folklore activities: “Komitas made a selection with the brilliant knowledge of the artistic merits and stylistic features of the Armenian rustic song. The recordings are masterfully performed and already bear the mark of Komitas.”8

Mansurian also highly appreciates Komitas Vardapet’s folklore activities, considering folklore an inexhaustible study material, an important boost to contemporary music development. The composer considers Komitas Vardapet’s interaction with folklore with Bartok’s approach to folklore.

Hungarian composer and folklorist Bartok highlighted the constructive patterns of folklore and the influence of rustic music on the composer’s work. Bartok was one of the first to propagate the thesis of combining folk music with atonal music.9

Bartok with his national features of composer thinking had a certain influence on the Armenian new composer school.10

To justify his unique approach to Komitas’ folklore, Mansurian refers to three versions of Bartok’s folklore. “Komitas perfected his work with such magnificence that he was equated with many distinguished composers who were outstanding in three forms of folk melody usage.”11

Half a century ago, the issue raised by Mansurian was a matter of discussion for both Armenian and foreign musicologists.12

Going deeper into the aesthetic principles of Komitas in folklore, Mansurian considers the issue of Komitas-folklorism from the development of modern music. He sees parallels between Komitas’ folklore and sonorism. Committed to the creative principles of Komitas Vardapet, Mansurian highlights the music of nature and color of live sound. “Komitas was one of the first to create his principles of returning to the color friendliness of the voice in his interpretation of European instruments (mostly the piano) and chorus, which was one of the first attempts to give freedom of tone and autonomy to world music in our era.” Mansurian evaluates Komitas’ collective art within the neofolklorism-sonorism interconnection. The composer correctly connects the issue of Komitas-folklorism, which has not yet been studied in detail, with “the world’s most controversial issues of modern world music.”

From the great artists, Mansurian separates Debussy-Komitas relationships, trying to find common features between the Armenian classical musician and Claude Debussy’s creative preferences. Mansurian’s sophisticated issue also needs clarification. The comprehensive study of this viewpoint will enable us to cover the Debussy-Komitas legendary link in a new light.13

Mansurian considers Debussy’s art one of the greatest revelations of modern music. The composer sees many contemporary music torchbearers who are influenced by the Great Frenchman (E. Varèse, P. Boulez, O. Messiaen). He identifies the creative aspirations of Debussy and Komitas Vardapet. The acknowledgment of Debussy-Komitas relationships in Komitas studies will confirm Komitas’ worthy place in the system of the world composers’ new way of thinking.

In highlighting the enormous role and achievement of the classical musician, Mansurian writes, “Komitas is more of a phenomenon. And he needs most of all to be the cornerstone for the solution of today’s most sophisticated issues of our musical art and to play an important role for Armenian young (and not only young) composers experiencing the complex process of self-awareness in contemporary world music trends. Looking at Komitas from this perspective we face many musical problems, which need to be studied.”

Many representatives of the post-Komitas composer school also came up with musical-theoretical activities. Not all Armenian composers overcame the restrictions and dogmas of speech and writing style that were imposed by the totalitarian ideology. In time, writers and poets (Yeghishe Charents, Paruyr Sevak, Nairi Zaryan, Hrant Hrahan, Hovhannes Shiraz, Vahagn Davtyan, Shahan Shahnur, Mushegh Galshoyan) even more often began to refer to Komitas Vardapet than composers.

Mansurian went on a different path. He developed his own style, like Komitas, to write in Armenian logic, to assess the reality and phenomena in an aesthetic, true and impartial manner. Mansurian’s articles are unique Armenian serious musicological studies based on the wide-range knowledge of the composer and musicologist-theorist and his analytical principles. Mansurian was one of the first in Soviet reality who bravely touched upon the “undesirable” authors (Schoenberg, Webern, Stravinsky) and “unsolicited” themes (modernity of serial technology, the importance of new sound relations).

In 1969, Mansurian authored the article “Let’s Recognize Our Genius,” dedicated to the 100th anniversary of Komitas Vardapet, in which he thoroughly examined the issue of “processing” Komitas for the first time, “Why is Komitas processed?”14 This issue is gaining a new importance today, but half a century ago raising this matter was a bold and even a defiant step.

Komitas Vardapet never used the term “processing.” In order to trump the existence of his own people’s art, Vardapet deemed his works modestly as “tunings,” which he “wrote down” from the Armenian peasant.

If a great number of Armenian musicologists relied on Komitas’ profound formulation, i.e. “tuning,”15 then the term “processing” would be ousted. (This topic of debate still needs to be clarified).

Many will share our opinion that Komitas’ genius music is not considered “arranging,” and it should not be subject to the low quality retunings or polyphonic tunings of musicians. For example, why are Josquin des Prez’ choral songs, the basis of which is folk song, not “processed”? “Processing” Komitas means to stay away from modern music culture development. Sharing Mansurian’s admirable ideas, we will quote some of his citations.

With a simple and brilliant example, the composer opposes “processors” of Komitas. “They think that Komitas’ works are obsolete, and they need to be arranged. The processors think they are doing the same thing as Komitas did. Komitas processed the folk song, and they are also processing songs. This situation resembles the naïve ambition of the man who is pressing the electric light button, thinking that by pressing the button he does the same thing as the man who invented the electric bulb.”16

As one of the first to acknowledge and recognize the exceptional place and role of Komitas’ music, its essence and perfected beauty, Mansurian opposes processors of Komitas by setting forth a very substantial viewpoint: “It is better to be like Komitas not by processing the melody of his works again, but by recognizing the art of our national musical art like our genius composer, by developing and establishing an approach and outlook of folk songs based on that cognition.”

By presenting the Armenian song and Komitas’ mission, Mansurian underlines the greatest discovery of Komitas: “The laws of our songs were discovered by Komitas. We did not have laws and regularities confirming the nature of those songs; Armenian songs did not have an autonomy certificate. This certificate was given to our songs by Komitas.”

It is known that Komitas Vardapet was the founder of not only the new school of Armenian composers, but also the founder of the science of studying ancient Armenian musical culture. Komitas Vardapet was a composer who founded his theory in Armenian music, with an unrepeatable and unique writing.

Komitas’ supreme mission was to prove the existence of Armenian independent music. “Armenians have their own music”—this reality was the credo of his creative life. Describing the regularities of Armenian music, Komitas wrote, “What gives a theme to national folk songs? Are those the proud mountains, deep canyons and valleys, the diverse climate, a thousand and one historic events, the inner and outer life of the people? Yes, all of this is a theme for national music, in a word, all that affects the nation’s senses and mind.”17

A self-described “modest” successor of Komitas’ work, Mansurian continues and develops his viewpoints and the basics of his creative style in his musical works. “The dominant part of the beauty of our music was born in nature, and it is similar to nature. Komitas created the art of Armenian song typical to his cognition, the constructive laws of which are the forms of expression of the laws of nature, with their everlasting aspiration to perfection,” writes Mansurian.

With his exceptional scientific and artistic talent, Mansurian addresses Komitas’ way of thinking and composer-constructive principles. “Komitas found the nature of our songs and the patterns of that nature. He made those patterns his own, made them the constructive basis of his art. On that basis, he created the unique polyphony unfamiliar to European music, created our criterion for musical thinking and our melody of musical movement. Komitas was one of the first in modern world music to give autonomy to intonation.”

Intonation is one of the most innovative and up-to-date aspects of 20th century music. In various streams of modern music, intonation has taken on an important constituent meaning. On the way to the development of modern music methods, Mansurian has always considered the art of Komitas Vardapet to be the true guarantee of his spiritual maturity and national background.

Mansurian also gives rise to contemplations. “Very often processed works are presented as Komitas’ own works. They distort the clear and straightforward, vigorous and pure, true and magnificent art of Komitas.”

In order to substantiate his clear orientation of the national music, Mansurian “struggled” for Komitas in various pages of the Soviet press, proving the role and significance of his art. We can assert that in the Armenian reality, few people are engaged with Mansurian’s patriotic activity.

Half a century ago, Mansurian sought to make Komitas’ art recognizable in the international world of music. The composer put forward the most important thesis concerning Komitas’ polyphony. “The historic role of Komitas is the polyphony born on the basis of patterns of our monophonic songs.” This baseline provision is the cornerstone of theoretical and analytical research in Komitas studies. “The Armenian rustic song with its versatile modal content and flexible rhythm has been a fertile land for Komitas to create his sophisticated and more original polyphonic forms,” writes Atayan.

The whole structure, polyphony and orchestral thinking of Mansurian’s music was born out of the modal monody, the basis of which was laid by Komitas. In the works of Komitas and Mansurian, the principles of polyphonic development are organically linked to the peculiarities of national music and the patterns of modern music.

In 1989, Mansurian wrote an article titled “With Him Day by Day,” analyzing the layers and folds of Komitas’ portrait, his arias and the unfinished opera Anoush. From a composer’s perspective, drawing interesting parallels (with Gaudi’s buildings), Mansurian considered the artistic merits of Komitas’ unfinished opera. For instance, Song of Plough of Lori is a song-improvisation of a large form (a drama of a people’s life). If Komitas were creating in more favorable conditions, he would have written an opera with a national background, based on a folk theme. Per Richard Wagner’s opera The Ring of the Nibelung, Komitas thought of writing Daredevils of Sassoun.18

In his most comprehensive and meaningful article, Mansurian touches upon the Komitas-Aram Khachaturian interconnection: “Komitas predicted the arrival of Khachaturian and was waiting for the birth of his music.”

Even several decades ago, Mansurian voiced the most burning issues of modern Armenian musicology, often prophetically foretelling the solution to those problems. “Khachaturian, in his turn, comes to Komitas in the field of melodic thinking – the fundamental element of music,” writes Mansurian. “For a moment, if we could leave out in our minds the whole burden of ornamental patterns of melody that accompanies it in Khachaturian’s music, we will have the same melody of Komitas, expressed in the most restrained and stingy ways.”19 To justify his view, Mansurian compares the melody of Komitas’ song Lorik with the melody of Khachaturian’s Violin Concerto.

Anahit Grigoryan, an Armenian music expert, has observed the Komitas-Khachaturian interconnection and its influence on the Armenian composer school. While she saw the bursts of Khachaturian’s epicism, she considered Mansurian the successor of Komitas’ artistic thinking and traditions.20

It is difficult to imagine the initial stage of Komitas studies without musicologist Ruben Terlemezian’s works, especially the Articles and Studies by Komitas Vardapet, published in 1941 and edited by Terlemezian. This collection has been of great scientific and cognitive significance over the years. Scientists dealing with the theory and history of Armenian music often refer to the ideas, theses and points of view expressed in articles by Komitas to support their arguments.

Taking into consideration the exclusivity of Komitas’ research, publishing house Sargis Khachents launched the Musical Series devoted to Komitas Vardapet starting from 2005.21

Publication of scientific works by Komitas Vardapet would be impossible without Mansurian’s participation. It is difficult to find the equivalent of Mansurian’s words in the literature devoted to Komitas studies. This is a totally new approach to Komitas Vardapet. Mansurian’s music is rational, finely woven and often difficult to perceive. Likewise the “inside” of his speech requires the knowledge of the material, the culture of reading and perceiving. Mansurian’s philosophical, sophisticated mind breathes life into the image and uniqueness of Komitas Vardapet – the Genius of Light. The scientific biography is written in a well-thought-out, solid integrity (in the logic of the composer’s preferred “trilogy”), with the possible inclusion of important facts.

Mansurian’s outstanding thoughts and formulations covering Komitas Vardapet’s mission are an inexhaustible piece of material for new music discoveries, many of which have become winged words. “We did not manage to take the challenges thrown by Komitas. This worries me a lot. I’d like people to worry in the future as well.”22

In 1969, Mansurian, lecturer in the theoretical-composer department of Komitas State Conservatory in Yerevan, authored “Komitas – a Great Reformer” in the newspaper The Voice of Homeland, writing, “It is truly a miracle that the centuries old accumulation of a people’s musical thought becomes the subject of one person’s study with all its secrets, vibrations, games and charms. And in particular, with his laws. This is a miracle. To be born with the mission of recognizing such accumulation means to be born with this accumulation in his soul, and it means to carry this huge burden. Is it not a heavy burden for one person?”

In 2019, we marked the 150th anniversary of Komitas Vardapet and the 80th anniversary of Mansurian; coincidence or providence from above? Armenian genius lives on.

___________

1. Lusine Sahakyan: Ferenc Liszt’s Appraisal by Komitas Vardapet. Anuario Musical (2012), No. 67, pp. 215-222. Lusine Sahakyan: Richard Wagner und Komitas Vardapet. Armenisch-Deutsche Korrespondenz (2016), No. 173, Vol. 4, pp. 31-33.

2. In his articles, Mansurian touched upon reviews devoted not only to Komitas Vardapet, but also Sayat Nova, Alexander Spendiaryan, Aram Khachaturian, Gustav Mahler, Igor Stravinski, Leoš Janáček, Dmitri Shostakovich, Edvard Mirzoyan, Alexander Arutiunian, Ghazaros Sarian, Edgar Hovhannisyan, Tatul Altunyan, Geghuni Chtchyan, Hovhannes Chekidjian, Nikoghayos Tahmizian, Avetik Isahakyan, Paruyr Sevak and Hamo Sahyan.

3. This article was published with advanced analytical section in the first volume of Komitasakan in the same year (pp. 84-121), as well as in 2009, in the collection of articles From the History of Armenian Music by Gevorg Geodakyan (pp. 222-267).

4. Lusine Sahakyan: Komitas Studies in Armenian Music Studies. Yerevan (2010), pp. 73-76. Mher Navoyan: The Concept of National Composer School According to Komitas. In: The Official Journal of the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin (2017), p. 118. See also Bibliography of Gevorg Geodakyan’s Printed Works. Yerevan (2015), pp. 11-12 (Mher Navoyan’s introductory speech).

5. Tigran Mansurian: Komitas – the Great Reformer. Voice of Homeland, 5. 11. 1969.

6. Svetlana Sarkisyan: Armyanskaya Muzika V Kontekste 20-go Veka [Armenian Music in the Context of the 20th Century]. Svetlana Sarkisyan (ed.), Moscow, 2002, p. 88.

7. See Robert Atayan’s introductory article in collection of works (1999), Vol. 9, p. 9.

8. Nikoghos Tahmizyan: Komitas and Armenian Musical Heritage. Pasadena (1994), p. 19.

9. Ioseph Uifalushi: Bela Bartok. Budapest (1971), p. 180.

10. Sarkisyan 2002, pp. 69-97.

11. Mansurian 1969, p. 13.

12. Alexander Demchenko: Folklorism and Problem of Chronotope in Komitas’s Works. Art (1991), No. 7, pp. 23-29. See also Atayan 1999, p. 26. Bela Bartok: Turkish Folk Music from Asia Minor. New York (1976). Tatevik Shakhkulyan: Some Parallels between Komitas and Bartok. In: Haigazian Armenological Research. Haigazian University press, Vol. 29, Peyrout (2009).

13. Debussy’s “meeting with Komitas Vardapet and his opinion” about him are recorded in many memoirs of Komitas studies. Lusine Sahakyan: Komitas Vardapet and French Culture. In: Kantegh. A Collection of Scientific Articles. Yerevan, 2016, Vol. 3 (68), pp. 242-263.

14. Tigran Mansurian: Let’s Recognize Our Genius. Literary Newspaper, 24.10.1969.

15. To tune – modulate, harmonize, adjust sounds, write music, invent. In: Explanatory Dictionary of Modern Armenian Language, Vol. 1, p. 468.

16. See In: Avangard, 31. 3. 1974.

17. Komitas: Articles and Studies. Yerevan (1941), p. 9.

18. Bakhtiar Hovakimyan: Theatrical World of Komitas. Komitasakan (1981), Vol. 2, pp. 242-261.

19. Ibid., p. 242

20. Alda Grigoryan: Live, Fruitful Tradition. Soviet Music (1981), No 2, pp. 118-124.

21. In 2005, Book A – Komitas Vardapet: Studies and Articles, in 2007, Book B – Komitas Vardapet: Studies and Articles, in 2009, Book C – Komitas Vardapet: Letters, and in the same 2009, Komitas in the Memories and Testimonies of the Contemporaries.

22. See in Garun, 1989, No 12, p. 12.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Robert ATAYAN: Elements of Polyphony in Armenian Folk Music. Komitasakan (1981), Vol. 2, p. 15.

- Ted AYALA: Lark Society Performs Komitas, Mansurian. CRESCENTA VALLEY WEEKLY, 6. 5. 2014.

- Bela BARTOK: Turkish Folk Music from Asia Minor. New York (1976).

- Alexander DEMCHENKO: Folklorism and Problem of Chronotope in Komitas’s Works. Art (1991), No. 7, pp. 23-29.

- Gevorg GEODAKYAN: Komitas’s Style and Twentieth Century Music. Soviet Art (1969), pp. 12-17.

- Alda GRIGORYAN: Live, Fruitful Tradition. Soviet Music (1981), No 2, pp. 118-124.

- Bakhtiar HOVAKIMYAN: Theatrical World of Komitas. Komitasakan (1981), Vol. 2, pp. 242-261.

- KOMITAS: Articles and Studies. Yerevan (1941), p. 9.

- Tigran Mansurian: Let’s Recognize Our Genius. LITERARY NEWSPAPER, 24.10.1969.

- Tigran MANSURYAN: Komitas – the Great Reformer. VOICE OF HOMELAND, 5. 11. 1969.

- Mher NAVOYAN: The Concept of National Composer School According to Komitas. In: The Official Journal of the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin (2017), p. 118.

- Svetlana SARKISYAN: Armyanskaya Muzika V Kontekste 20-go Veka. Moscow, 2002, p. 88.

- Lusine SAHAKYAN: Komitas Vardapet and French Culture. In: Kantegh. A Collection of Scientific Articles. Yerevan, 2016, Vol. 3 (68), pp. 242-263.

- Lusine SAHAKYAN: Richard Wagner und Komitas Vardapet. Armenisch-Deutsche Korrespondenz (2016), No. 173, Vol. 4, pp. 31-33.

- Lusine SAHAKYAN: Ferenc Liszt’s Appraisal by Komitas Vardapet. Anuario Musical (2012), No. 67, pp. 215-222.

- Lusine SAHAKYAN: Komitas Studies in Armenian Music Studies. Yerevan (2010), pp. 73-76

- Tatevik SHAKHKULYAN: Some Parallels between Komitas and Bartok. In: Haigazian Armenological Research. Haigazian University press, Vol. 29, Peyrout (2009).

- Nikoghos TAHMIZYAN: Komitas and Armenian Musical Heritage. Pasadena (1994), p. 19.

- Ioseph UIFALUSHI: Bela Bartok. Budapest (1971), p. 180.

Be the first to comment