Original piece by Hagop Gyuloian (published by Asbarez in 1997)

The white-haired Hovhannes Atamian, a carpet weaver, is working in his abode with a searing focus on the old and highly-valuable carpets he rescues from time and deterioration, and with great delight, recounts tales from the past, to which I bore witness in my youth.

That evening, Hovhannes was late to the usual in-club gathering. We knew he had projects to submit whence he returned with a great sense of pride and fulfillment. That evening, however, he was a different man; excess reddening of the face, eyes brimming with soul-wrenching tears, irrigating an existential dread, our gaze shaming us into evading his sight. That evening, Hovhannes wasn’t our Hovhannes. With trepidation, we inquired further in order to dispel the stranger before us.

“I need a kindergarten-level Armenian textbook.”

“What for?”

“I am going to learn how to read and write Armenian.”

His reply was unexpected. A young Armenian who didn’t know Armenian?

His deep sorrow and tear-laden expression cast a silence among those around him.

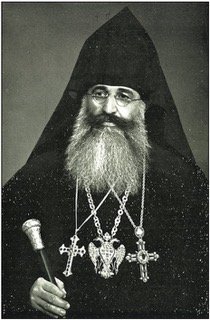

“Today I took two newly refurbished carpets to Patriarch Gyuregh. He observed astoundingly.”

“’Not even the slightest sign of renovation. Bravo. What do I owe you?’ He asked and waited.”

“I didn’t know what to answer. I had dedicated six days to this endeavor. My weekly fee was 50 ghouroush. And that’s what I told him.”

Patriarch Gyuregh took out 50 ghouroush and placed it on the table along with a piece of paper upon which he wrote, then said: “Here is the receipt. Sign it and take what you’re due,” pointing to the dotted line. I signed and handed it over. He glanced at the signature, and his face transformed sullenly. A sharp gaze befell my face followed by a sharp slap that sears to this day; the impulse to even look back at him abandoned me.

“What have you signed?”

“My name and family name,” I replied.

“But, this isn’t Armenian.”

Buried with shame, I muttered: “I don’t know how to read or write in Armenian. I did not attend an Armenian school,” as I directed my steps toward the door.

“Wait a minute! Take the 50 ghouroush as well as that bag containing two carpets. Renovate them and swiftly bring them back!”

“I took the carpets, but I refused to take the money lest I felt the weight of his palm again!”

“Where are you going? Come back! Take your 50 ghouroush and leave! Bring them back before Christmas!”

“Now, I will learn to read and write in Armenian and sign in Armenian!”

…

The days tumbled forth, and with them the refurbishment was complete. With every step, Hovhannes repeated then enunciated the newly learned Armenian alphabet. His signature saw life in many forms, whence he finally adopted his own; his patron and clients became his tutors — serving as canvases upon which he laid his novitiate strokes.

Two days before Christmas, jovial and proud, Hovhannes appeared before Patriarch Gyuregh, carpets in hand, greeted with appreciation and felicitation.

He prepared the receipt and prompted Hovhannes to sign. Upon reception, flabbergasted, he said: “Then why didn’t you sign in Armenian the last time?”

“I didn’t know how to read and write in Armenian then. I learned, and now I know.”

Silence grasped the room, jolting stillness to life. Tears silently flowed down Fr. Gyuregh’s stern yet kind eyes, in unison with the bell tolls of Christmas Eve.

That slap had bestowed a love and recognition for the Armenian letter, for the Armenian language. Tears of happiness…

Our love for the kind yet strictly dutiful Fr. Gyuregh had doubled. Hovhannes’ generation was spared; a slap had hijacked destiny and traveled to the marrow of his Armenianness. Over time, Hovhannes started to read euchology, Nareg, Armenian history and literature.

Upon his first chance, he went to Armenia with his family. His father had lost all of his relatives during the Armenian Genocide. He had found refuge at the Ararat orphanage. In order to retrieve his lineage, he managed to erect a family within the cradle of holiness, sprouting bountiful branches from his name. Alas, the thorns of Siberia had pricked the bulk of his tale. The salvaged light, usurped from the darkness of Turkey, had all but extinguished within the morbid plains of Siberia. The fate of Armenians…

Hovhannes remained by himself, his patriotic sentiment legitimate and rich. Luck had flung him to Armenia, where he had formed a family with many delightful children. Life had taken him to newer pastures across the seas. He had arrived in America. Eventually, his longing for the East led him to Lebanon, with a watchful eye toward finding long lost relatives, whom he met with joyful warmth.

And now, with the serenity of a victorious man, he remembers both the just and unjust passings and faces. Alas, Patriarch Gyuregh’s slap, akin to a masterpiece within the center of a museum, undimming and steadfast, a peerless memento within Hovhannes, beckoned a tear.

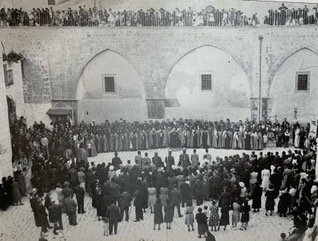

Patriarch Gyuregh, the principal of Tarkmanchatz, the darling of the students, would summon them to the Grand Hall before every feast for Khosdovanank, a moment noted by both the nourishment and discipline of their souls in preparation for the Kingdom of Heaven, whence his words were imbued with the spirit of bygone voices. A moment’s worth for the dispersal of our sins in search for worthiness of the Sacrament of Holy Communion. Alas, under the weight of our sins, his constrained soul diffused within his tears, and through that, we believed and saw the saints of our past.

“Woe to me, woe to me, my sins are unspeakable.”

“I have sinned against God.”

“May God grant you forgiveness.”

And now, every time I find myself at confession, I am faced with the silhouette of Patriarch Gyuregh, honest and whole, akin to Khrimyan Hayrig, who is far from Jerusalem, but ever-present and close, a man of the people, who presided over every funeral procession that involved martyrs who had perished during the war, consoling the families in mourning. He believed that every man who did the utmost for his nation and countrymen ought to be impervious to the notion of refusal, and he lived the totality of his life with that very same conviction.

Today, along with Hovhannes the carpet weaver and his generation of students, we reminisced about the purity of his demeanor and character; all issues aside, he managed to uphold the stature of the Patriarchate, and within our handful of lands, ensured equitability and honor, refusing to loosen the grip on the values that mapped the trajectory of the convent.

His life belonged to the convent, the nation and God. His tear remained a blessing for all Christmases to come. The reverberations of his slap, so precious and rescuing, so needed today, for the appraised future of our youth and for the plethora of roads to be taken.

It is then that the joy of Christmases to come will grow. It is then that the bells of the world will toll.

Be the first to comment