As an inseparable part of the Armenian highlands, Artsakh has not remained without the traditions of viticulture and winemaking. As one of the important regions of pan-Armenian viticulture, Artsakh’s soil is home to the “Khndoghni” (also known as Sireni) type of grape, from which various red wines are made.

In 2014, a wine festival was held in the Melik mansion of Togh in the region of Hadrut. Its purpose was to revive and continue the traditions of Artsakh winemaking. The annual festival, which featured traditional dishes and wines, rallied around Artsakh and Armenian winemakers.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that the most successful Artsakh wine, Kataro, was produced in Togh. The ancient Kataro Monastery, which decorates the top of the Dizapayt mountain in Artsakh, became a source of inspiration for the Avetisyan dynasty.

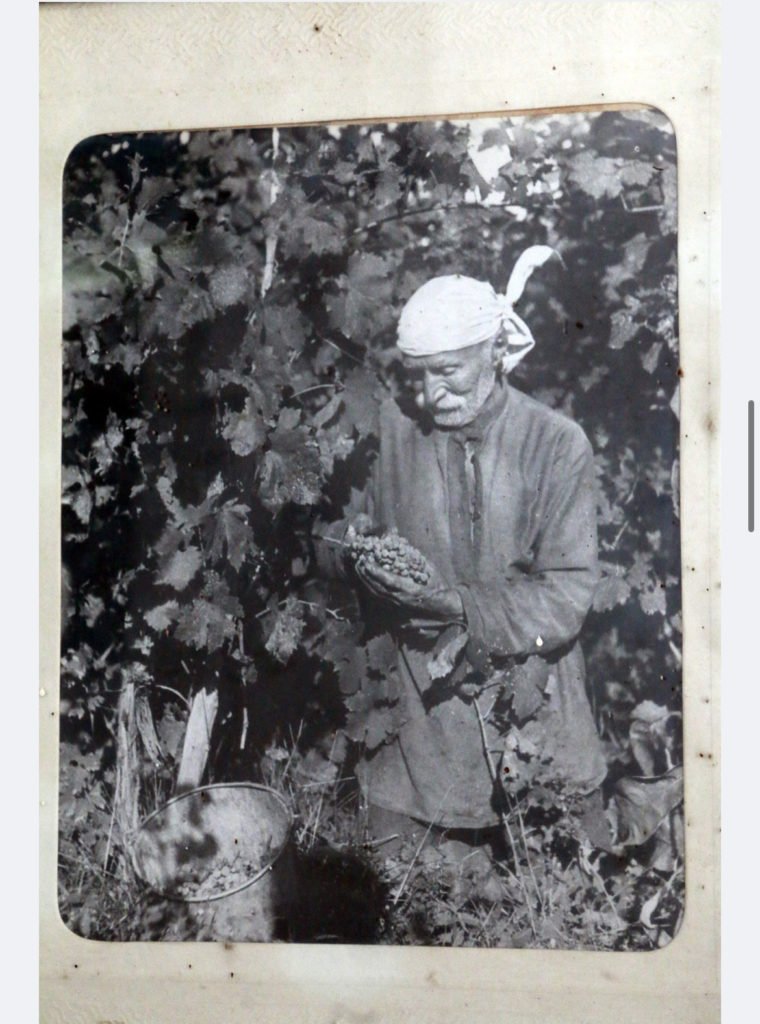

Grigory Avetisyan was inspired by a 1930s photograph of his great grandfather cultivating his vineyard when he founded Kataro Wine Factory almost a century later in 2010. Since then, red and white varieties of Kataro wines as well as Kataro Reserve have been delighting wine enthusiasts and connoisseurs around the world.

The Artsakh War of 2020, however, was detrimental for Kataro. At the factory, workers had collected grapes brought from different regions of Artsakh. They were going to harvest grapes from their garden when their work was interrupted by Azeri shelling. Along with most of Artsakh, all of Kataro in Hadrut was also lost. Avetisyan said they managed to save only 10-thousand bottles of the Kataro Reserve, which they auctioned for Kataro’s revival.

Today, in Dzoraghbyur in the region of Kotayk, which lies 20 kilometers outside Yerevan, there is work being done at the reopened Kataro factory, which is processing the Khndoghni/Sereni varieties from Artsakh. There was never any hesitation to reopen the factory. Winemaking for Avetisyan is a way of life, a symbol of struggle. Today, his father, two brothers and their children work with him. Kataro wine is a family story. “Nothing has changed. We work at the same volume,” he said, noting their upcoming release of 120-thousand bottles of wine. “We bring most of our grapes from Artsakh. The geography of export has not changed either. Even the workers are the same. They are the residents of our village, but internally displaced people. The only and most important change is that we are far from Hadrut and Togh,” he shared.

winemaking is a means of healing after the war

Nephews Eduard and Vanya, who are studying winemaking, work at the factory. Vanya was a conscript soldier during the war. He says he misses the village the most, because he was away from home and the factory for two years while serving in the army. For Vanya, in addition to continuing the work of his grandfathers, winemaking is a means of healing after the war. “Doesn’t winemaking combine philosophy and psychology? That’s the only way we can overcome the disaster we went through,” he says with a sigh. Vanya remembers with pain his friends who died on the battlefield and the last messages they left behind.

“The most important thing is to make wine with love. Wine itself is love. Our wines are heavy and serious like us,” says the future winemaker whose favorite wine is Kataro’s Reserve, which was also obtained from the Khndoghni variety. It was kept in the oak casks of the Hadrut region for a year. Every time he drinks it, he remembers his village, his home and his garden.

Winemaker Andranik Manvelyan has been working with Kataro since 2019. During the war, he worked at the factory with volunteers from Yerevan who came back from the frontline and tried to propel Kataro’s winemaking. “For me, Kataro is a brand, a way of life, and also a symbol of my friendship with Grigory. After overcoming so many difficulties, we want to develop it further. Now we are more motivated,” Manvelyan says. “Kataro was and is a combination of grape varieties from all regions of Artsakh, and therein lies Kataro’s power,” he added.

Be the first to comment