Hakob Karapents novels translated into Farsi

Coinciding with the 95th birth anniversary of prolific Diaspora Armenian writer Hakob Karapents, two publishing houses in Iran have announced the release in Farsi of his works: Ketabeh Adam [The Book of Adam], the writer’s most celebrated and popular novel by Khazé Publishing, and Yek mard va yek sarzamin [A Man and a Land], an anthology of 15 short stories and essays by Siyamak Book (Ketab-E-Siyamak). This is the first time that works of Karapents are published in the country of his birth. These publications will provide the first opportunity for the Farsi-speaking community and literary circles in Iran to become acquainted with Karapents and his unique literary legacy as well as his Armenian compatriots who will read his works in Farsi for the first time.

Ketabeh Adam has been translated by Andranik Khechoumian, celebrated Iranian Armenian writer, playwright and translator. The book includes an introduction and a brief biographical sketch of the writer by Ara Ghazarians, curator of the Armenian Cultural Foundation, and a preface by Abbas Jahangirian, prominent Iranian writer and literary critique.

The Book of Adam is Karapents’ second novel. He wrote it a decade after his first novel, the Daughter of Carthage (1972). He began writing it in mid-1980 and completed it in less than a year time. The book is dedicated to his wife Alice. It received rave reviews by several Diaspora Armenian literary critiques. It is the winner of the Armenian General Benevolent Union’s (AGBU) Alex Manoogian Literary Award and French-Armenian Writers Society’s Eliz Kavookjian-Ayvazian Literary Award. The second edition of the novel was released in Armenia in 2012.

The novel has also been twice adapted for the stage, once in Tehran (2005) in honor of Karapents’ 80th birth anniversary under the direction of Seto Gojamanian titled “Where are we to be buried” and then in Los Angeles (2017) by Armen Sarvar titled “Yes, Adam Nourian.”

The Book of Adam is constructed on three levels: the state of the American social order in the final decades (1980s) of the twentieth century; the current crisis of the Diaspora Armenian; and the crisis of man finding himself at the end of the twentieth century. The characters and plot serve as the means of linking this triad of knots together and reaching a certain truth. “Aside from flashback,” as observed by the late editor, writer and translator Aris Sevag, “the book is written to understand life by the return trip and to live life by the road ahead, the metaphysical with the real, sometimes relying on non-existent realities which are more powerful than the real; therefore, from tie to tie, there surfaces a dry journalistic style to produce a clash between tangible and intangible realities. From this standpoint, the Book of Adam enters the self-contained current of contemporary American literature, which is a sad and nondescript visit to solitary persons and solitary communities.”

The second book, Yek mard va yek sarzamin [A Man and a Land] is divided into five sections, includes 12 short stories and three essays, selected from Karapents’ following titles: Mijnarar [Interlude] (2), Amerikyan shurjpar [American Rondo] (3), Ankatar [Incomplete] (4), Mi mard u mi erkir [A Man and a Country] (3), and Erku ashkharh [Two Worlds] (3). Dedicated to her mother, the compiler, translator, Armenoush Arakelian presents a tastefully written preface in three languages (Armenian, Farsi, French), as well as a brief biography of Karapents and his literary legacy. The selected pieces represent diverse aspects and dimensions of Karapents’ work, unique linguistic character and literary style, which according to Arakelian even has “poetical resonance.” Arakelian, a translator and editor born in Tabriz, Iran, is a graduate of the Sorbonne University, majoring in French. She has been active on the Armenian cultural and literary scene in her country of birth. She has collaborated with Alik daily, Payman Quarterly and Ararat Bulletin and has co-edited and translated six books.

In Arakelian’s words “Karapents ushers the reader to the multilayered and multifaceted world of his characters, their lives and events. The heroes of his works are alive, vibrant and not restrained by the rules of the world in which they live. He penetrates into the inner world of the man, probes their souls and reflects their feelings and dreams.” For Karapents’ life, a mix of bitter episodes and cycles of happiness are always incomplete; man is in perpetual search of happiness and perfection.

Arakelian says Karapents’ stories are “captivating and filled with delicate feelings of love as well as the spirit of eternal struggle.” His stories are also replete with expressions of criticism and protest against tyranny, injustice and sham slogans of human rights. In Karapents’ words, “Even in wisdom there is white wrath, which emanates from the unjust’s ever present fixation.”

This is the first time that Karapents’ works in general and short stories in particular are presented in Farsi in one volume. Prior to the release of Yek mard va yek sarzamin only a couple of his essays and biographical sketches about his life and literary legacy had been published in the Farsi-language in the Armenian Payman Cultural Quarterly (no. 9/10, no. 53) and Mirza magazine. Hopefully, the above titles will inspire other scholars and literary figures to undertake similar projects and make Karapents’ rich and unique literary legacy available to wider audiences in Farsi-speaking communities worldwide.

Many years ago, in an answer to an interviewer’s question about writing in English, Karapents responded, “Many encourage me to write in English…in order to partake in the American literature, one has to be an American. I am an Armenian, a Diaspora-Armenian, which is a unique creature in the history of mankind…I have lived for many years in America, however I do not consider myself an American. Despite all, my Armenianness is my identity, my license to walk among the crowds and feel that I am different.”

This conviction, to which Karapents remained loyal during his entire literary career, unfortunately, for decades, deprived non-Armenian speaking readers, English in particular, of a rich literary treasure. Karapents’ works were not fully appreciated among his people either since he wrote in Eastern Armenian in a Western Armenian speaking reality. Furthermore, his works sadly, falling victim to Cold War politics, remained inaccessible in Soviet Armenia, thus depriving even his compatriots from a unique literary genre and scope of contemporary Armenian literature.

In the final years of his life, Karapents was persuaded to make some of his works available in English. He finally agreed to have some of his short stories translated into English. Return and Tiger—a collection of 15 short stories translated by Tatul Sonentz Papazian and published by Blue Crane Books—was sadly released a couple of months after his passing in 1994. This was followed by the publication of another anthology—a collection of seven short stories by the young Hakob Karapents written in 1950s, titled Widening Circle and Other Early Short Stories, in 2007.

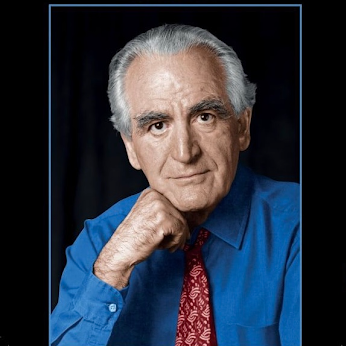

Hakob Karapents was born in Tabriz, Iran in 1925 to Armenian parents with roots deep in historic Artsakh. He moved to the United States in 1947 and studied at Kansas City University and majored in journalism. Later he attended Columbia University where he studied psychology. In 1954, he joined Voice of America, where he worked over a quarter of a century and served as the Chief of the Armenian Service. After his retirement in 1979, Karapents moved first to Connecticut and later in 1989, after a decade of self-imposed seclusion, to Watertown, Massachusetts, where he lived until his death in 1994.

Karapents is the author of over 900 articles in Armenian and English, 90 short stories, two novels, as well as essays, commentaries, book reviews, etc. In accordance with his wishes, his library, publications, personal effects and memorabilia were donated to the Armenian Cultural Foundation of Arlington, Massachusetts, where an entire room is dedicated to his collection and papers. In 1995, the Yerevan City Council dedicated No. 6 high school after Karapents, where a small museum was also established in recent years. In the final days of his life Karapents expressed his wish to establish a scholarship under the auspices of the Hamazkayin Cutural and Educational Society, Armenia to support promising youth pursuing careers in journalism, literature and philology. Since 2000, over 130 deserving students from various higher academic institutions have received annual scholarships. The Scholarship Fund in the United States is managed by the Amaras Art Alliance, a non-profit, tax-exempt organization registered in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.