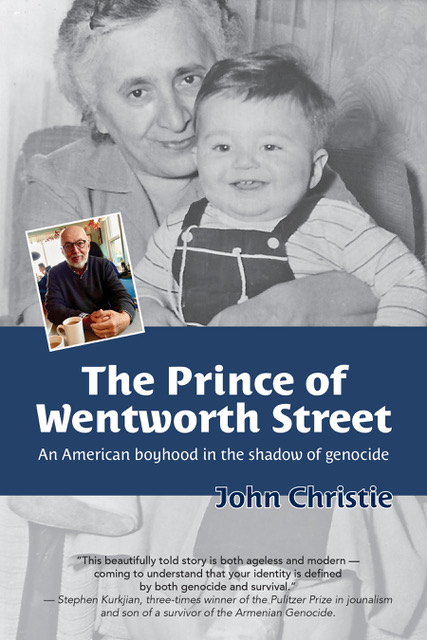

The Prince of Wentworth Street

The Prince of Wentworth Street

By John Christie

Plaidswede Publishing, 2020

177 pp.

Armenians have been testifying and writing family histories almost since the 1915 Armenian Genocide. Zabel Yessayan famously spent long days and nights in Tbilisi taking down first-hand testimonies of survivors. Since then a whole genre has appeared of second and third-generation descendants writing down their family history as a way of anchoring their own selves within this history and answering the continued Turkish denial of the terrible event itself. John Christie’s new book The Prince of Wentworth Street makes a solid contribution to these accounts.

Christie’s account begins when he is in his sixties and visiting a group of returning campers which include his second wife’s grown children, who have been part of the program for years. What should be a time of exultation for all however, throws Christie into a deep despond. The author comes from working class Catholic stock and rose from humble beginnings in the late 1950s in Dover, New Hampshire to become a noted journalist and publishing executive; his wife hails from a more affluent Jewish middle-class background and attended an unnamed progressive private school in New York City. Somehow the disparity in background and the situation itself—the author never fully explains the precise trigger in question—sends Christie on a quest to find out about his family background.

Through a recording made by his cousin Tammy, Christie and the reader learn about his Nana Gulenia Hovsepian’s escape from Suedia in the Cilician Alexandretta province of Western Armenia and the long trip that she and her siblings made to Lebanon, Egypt and eventually the United States. The details of the family’s treatment in Turkey before and after the Genocide are harrowing but will not surprise those familiar with the events: one ancestor was axed to death before the Adana massacres of 1909 and left to die in an open field. Like others before him, Christie eventually returns later in life with his son Nick to the small village in Vakifkoy—Musa Dagh—where his family originated, to find his ancestral house.

Christie’s mother Kay (“Koharig”) was born in Dover where she attended high school and married John’s father Thomas, a quiet Irishman who worked in the local mills, where she too went to work after his untimely death at 50. The most compelling parts of the book describe John’s childhood on Wentworth Street where his Nana and parents spared no effort to make sure that he had everything he needed to succeed—hence the title of the book. The hard work and self-deprivation that he describes rang true with this particular reviewer, whose own parents went to similar lengths while he was growing up in New York City.

Along the way, we learn details about John’s Catholic school education (stern, but solid), his joining a group of smart rebellious boys who all ended up doing well in life, as well as the more tragic story of his younger brother’s battle with drugs. The institutions that marked his life—family, the Catholic church and Boy Scouts—all emphasized character and honesty. Christie belongs to that group of American immigrant children who were the first to attend college and who all carved a piece of the so-called American Dream for themselves. The Prince of Wentworth Street is ultimately a piece of immigrant history that transcends the Armenian Genocide. At times Christie’s prose becomes poetic, like when he describes life in the early 1960s: “All of that—the blood pooling on the jungle floor in Vietnam and staining a pink dress in Texas and spilling onto a balcony in Memphis—was about to enter our consciousness. But that night we were just on a crazy lark. Like Dylan Thomas playing Indians, we were aware only of ourselves.” Interestingly enough, Christie skips describing his career and marriage almost entirely. One assumes from the rest of the book that he navigated these with the same firm work ethic and kindness that seems to have guided the rest of his life.

Be the first to comment