Think of major trading ports in the 16th and 17th centuries, and you can be sure Armenian merchants visited them. One such port was Malacca (Melaka) in Malaysia. With its historic city center, listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Malacca is today a popular tourist destination and to the surprise of many, Armenians once lived there.

Captured in 1511 by the Portuguese, Malacca began to flourish with traders from Europe, Asia and Africa. Needless to say, Armenians were among them. While some Armenians carried their own cargo, others acted as middlemen. To break the long journey from Europe, they stopped in India at Gujarati ports, especially Surat, selling goods such as opium, rose-water, silver, arms and glass. After re-stocking with textiles, indigo and pearls, they caught the monsoon winds down to Malacca. When the winds changed direction, these merchants headed back to India via the Maldives with their vessels laden with spices, sandalwood, porcelain, gold, silk and damask. In the intervening months, the merchants and seamen needed accommodation and safe storage for their goods. Malacca provided both.

In 1641 the Dutch captured Malacca. Its importance as a trade nexus decreased, although it still attracted a significant share of traders including Armenians from Persia and India. Malacca became a regular port of call in the trading network established by the New Julfa merchants from Isfahan. Their other destinations included Canton (Guangzhou), Pegu and Syriam (Thanlyin) in Myanmar, as well as Manila and Batavia (Jakarta).

Armenians were living in Malacca in the late 1600s, while in 1711, traveler Charles Lockyer remarked that among its inhabitants were two or three Armenians. Although Lockyer regarded them as honest and fair traders, he commented that the Dutch had no time for them.

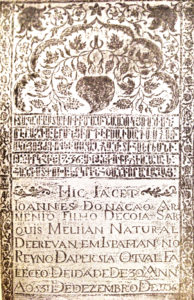

Five tombstones are the only evidence of these transient traders. The oldest is that of Johannes Sarkies which once lay in St. Peter’s Church.

The transcription from the Armenian (Photo 3) reads (non-literally):

In this tomb is enclosed the body of young Johannes who came originally from Yerevan. He was the son of Sarkis, a most esteemed merchant. He died at 30 years of age in the year of the Saviour 1736; and in the little era [of Azaria] 121, the 5th of Aram;

May he rest in peace in this Dutch land called Malacca.

The paraphrased Portuguese script reads slightly differently:

Here lies Johannes an Armenian, son of Khojah Sarkies Melijian, a native of Erevan in Isfahan in the kingdom of Persia. He died at the age of 30 years on 31 December 1736. (Erevan was one of the Armenian quarters in Isfahan.)

The second tombstone (Photo 4a), found in the ruined Church of St. Lawrence (San Laurenço) belonged to Tarkhan Chouqourents, son of Ovanjan, who died on January 4, 1746. Today it rests in the Stadthuys Museum along with an unidentified Armenian tombstone.

Bearing traditional Armenian funereal motifs and ornamental designs very similar to those on Jacob’s tombstone, the owner of this partial tombstone (Photo 5) remains a mystery.

Bearing traditional Armenian funereal motifs and ornamental designs very similar to those on Jacob’s tombstone, the owner of this partial tombstone (Photo 5) remains a mystery.

The famed tombstone of Jacob Shamier (Photo 6) is embedded in the central aisle of Christ Church. It displays a skull and crossbones, together with the crest of the Shamier family. This comprised a pair of scales with small weights for weighing precious stones, plus an ink pot and quill. Also shown are Jacob’s tools of trade—scissors and tape measure.

Jacob was a scholar as well as a merchant. In 1772, he had set up the first Armenian press in India and published a pamphlet entitled Exhortation which aimed to arouse patriotism in the minds of young Armenians. Hints of his own fervent feelings can clearly be seen in his epitaph.

Hail to thee who readest the epitaph on my tomb!

Give me the news of my nation’s freedom, for which I have passionately longed.

[Tell me] if someone has risen among us, as deliverer and leader; which, while on earth, I so earnestly desired.

I, Jacob, scion of respectable ancestors from Armenia

I received the name Chamrchamian

I was born in a foreign land, at New Julfa, a town in Persia.

On attaining twenty nine years of age, I accepted my destiny

on the seventh of July, I reached the end of my life,

In the year of the Saviour 1774, I laid myself down to rest in this grave, which I had bought.

The Dutch epitaph reads simply: Here lie the remains of Heer Jacob Shamier, Armenian merchant, who died on 7 July 1774 in his 29th year.

An Armenian priest from the US, who had heard of the plaintive plea on this tombstone, traveled to Malacca after Armenia gained independence in 1991 to ‘tell’ Jacob that his country was free.

Dutch rule ended in Malacca in 1795, when the British temporarily occupied it until 1818. One ill-fated voyage during that time was that of Johannes Seth who had journeyed from Surat to Madras (Chennai), then boarded the Ararat, arriving in Penang in 1796. After selling most of his cargo and picking up new goods, he sailed on to Malacca. Unfortunately, the Ararat was attacked by the French who were at war with the British. The Armenians were put ashore in Penang, but the entire cargo was confiscated.

Under British rule, however, a few resident Armenian merchants prospered. They included Jacob Minas and his family who lived in a grand mansion on Heeren Street. After Jacob died in August 1806, his son Joseph became head of the family, as well as the spokesman for the handful of Armenian merchants.

In December 1816, they presented an appreciative farewell letter to tax collector John MacAlister. Thanking him for his integrity and lamenting his departure, they wished him well for the future. The letter was signed by Joseph Minas, Marcar Carapiet, Sarkies Arratoon Sarkies and Harapiet Simon.

In reply, John MacAlister thanked the Armenians for their gratifying remarks and hoped they would ‘individually continue to enjoy that health, happiness and prosperity which [their] industry, probity and general good conduct so eminently merits.’

Joseph Minas and a Mr. Shamier made the news in October 1821. They were passengers on Catchatoor Galastaun’s brig Covelong traveling back to Malacca from Penang, when it stopped to help another vessel in distress. The men gave up their cabins to the women and children rescued from the stricken vessel. When thanked publically by grateful husbands, the pair gallantly replied that the agreeable company of the ladies on board was sufficient thanks for the inconvenience they suffered.

Armenians from Rangoon (Yangon) and Penang continued to trade with Malacca. They included Petrus Arratoon who captained the Nancy, Isaiah Zechariah, Johannes Carapiet, Harapiet Gabriel and Jordan Mackertoom.

However, by the 1820s Malacca, which was now back in Dutch hands, was in a backwater. In 1819 Singapore had been established as a British free trade port and realizing that it offered better prospects some Armenians migrated there, including Sarkies Arathoon Sarkies and Aristarkies Sarkies (who were not related). Marcar Carapiet moved to Penang as did Joseph Minas and his family in December 1822. After Joseph’s death the following May, the family returned to Malacca, but sold up in 1829 and they too, settled in Singapore.

In future years, few Armenians lived in Malacca. In the early 1870s, an M. Sarkies was listed as a planter at Merlimau.

In 1886 Singapore lawyer Joe (Joaquim) P. Joaquim (Hovakimian) and sister of Agnes, who hybridized the orchid which became Singapore’s national flower, opened a branch office in Malacca. Originally run by English lawyers, the firm was called Joaquim, Groom and Everard. Joe’s younger brother Carapiet was the senior clerk. He married Eliza Rodyk; their five children (Conrad, Maria, Joseph and Elisa) were born in Malacca. After Eliza died in childbirth in 1900, Carapiet and the children moved back to Singapore where Carapiet set up as a broker. He remarried in 1903, but the following year, committed suicide because of financial problems.

In 1889 John Joaquim, who had followed Joe’s footsteps to Middle Temple in London, was admitted as a barrister to the Straits Settlements Bar. In 1890 he moved to Malacca, taking charge of the office after Robert Groom left. The firm then became Joaquim and Everard, but after James Everard died in 1891, it became Joaquim Brothers. For the next decade Joaquim Brothers, headquartered in Singapore, was one of the leading law firms in the Straits Settlements.

John, like his brothers, did not marry an Armenian, but chose Frances Poundall, whom he had met in London. The couple’s second son Basil was born in Malacca in 1890; he went on to become a prominent Malayan lawyer. In 1896 John, Frances and their three children settled in Kuala Lumpur where John managed another new branch of Joaquim Brothers.

Younger brother Seth, who also qualified at Middle Temple, was admitted to the Straits Bar in 1893 and soon took charge of the Malacca office. He too, had married an English girl—Ellen Young—but they had no children. In 1904, Joaquim Brothers was dissolved after the untimely deaths of the three brothers: Joe in 1902 aged 45, followed by John aged 46 and Seth aged 38 in 1904.

The only other Armenian family known to have lived in Malacca was that of Philip E. Aviet. Aviet was born in Madras in 1865, a son of Thomas Aviet and Julia Rencontre. Having joined the Eastern Extension Australasian and China Telegraph Company in 1884, he was transferred to Singapore, then on to Malacca in 1895. In Singapore, Aviet married Louisa Oehlers where the couple’s first three children were born. The next four were born in Malacca including Eugene who became a respected doctor in Malaya. The family spent over 15 years in Malacca before migrating to London in 1922.

Despite their minute numbers, the 1891 census listed four Armenians and the 1901 listed six. These were the Joaquims. Considering that Malacca’s population exceeded 91,000 in 1891 and 95,000 in 1901, it is surprising that they were included in the censuses. Probably fewer than 50 Armenians have lived in Malacca, and today the only visual reminders of their presence are the five tombstones.

For more details, see:

N. Bland. (1905) Historical tombstones of Malacca mostly of Portuguese Origin, London: Elliot Stock.

Macler. (1919) ‘Note sur quelques inscriptions funéraires Arméniennes de Malacca’, Journal Asiatique, 11th series vol. 13: 560-568.

Susan E. Schopp. ‘Up from the Watery Deep, the discovery of an Armenian gravestone in the South China Sea’, in Armenians in Asian Trade, 263-5, at https://books.openedition.org/editionsmsh/11412?lang=en

Nadia H. Wright. (2003) Respected Citizens: the History of Armenians in Singapore and Malaysia. Middle Park: Amassia Publishing.

Thank you Ms. Wright for everything you do in this regard. Very interesting.

Thank you Nadia for your interesting research . My wife is from kedah , MAlaysia had a DNA test by livingdna , and identified 6.2 percent armenian/ Cyprus heritage , which roughly translates possibly to 4 generations ago ( 2-300 years ago)some Armenian ancestor . From your research do you know what likely places the Armenians would have migrated from to Malaya in the 1700-1800s.?

Dear Nadia Wright. What an amazing story. Thanks for sharing this. Thanks for your extensive research of Armenians in South East Asia. By any chance would you be willing to travel to Southern California to give a comprehensive talk? Your knowledge is invaluable. I may be able to arrange such a trip.

Three years ago, I was in Singapore and by chance I met a direct descendent of Sarkies brothers. I wanted to conduct an interview with her. But it has not happened yet. If you receive this message please let me know. My email is: cyesayan@gmail.com

Dear Catherine: Thank you for your kind reply and I will email you. However I must point out a misconception. There are no direct descendants of the Sarkies brothers in Singapore. The last ones – the children of Aviet Sarkies- left in 1910.

Few years back we visited Singapore’s Armenian Street, The Church and read the inscriptions of The tombstones of those

famous merchants and personalities, who played a big roll in stablishing Singapore. Visited the famous “Raffle Hotel”

tasted their expensive “Singapore Sling” Drink created by the Armenian owner. We also visited The Singapore National

Garden, witnessed the famous Tulip named to Joaquim Agnes (The Armenian Lady)

I believe the Armenian priest who went to pray over Jacob Shamier’s tombstone to respect his wish to be informed of Armenia’s independence was Srpazan Mesrob Ashjian, Archbishop and prelate of the Eastern Prelacy of the US.

The overly expensive Singapore Sling was created by Ngiam Tong Boon the bar tender at the famed Long Bar.

Agnes Joaquim (Ashkhen Hovakimian) hybridised the orchid named after her -the Vanda Miss Joaquim – which was selected as Singapore’s national flower in 1981.

Thank you for adding that information Mike.

Thank you for the information Mike.

Another useful article on the under-researched 18th-20th century history of Armenian traders, business pioneers and settlers in Southeast Asia. Here on Malacca, Malaysia. Thank you Nadia.

Thank you Noric.

Thank you Haro.

Dear Nadia,

Few months ago I purchased your book in Sydney, entitled ‘Respected Citizens, The history of Armenians in Singapore and Malaysia’.

A great review of the history of Armenians in that part of the world.

Much appreciation for your diligent historical review.

Regards,

Artin Jebejian

Dear Artin:

Thanks for your positive comments.

krs

Nadia Wright.

I have a copy of the Asia Magazine of 1968 featuring the Armenian community of Singapore. An elderly gentleman by name of Carapiet was in the article. That following year, I was in Mymensingh attending a local university and got to know a Christian family living next to the church. I was curious about their surname which was Carapiet. They spoke very little English, very poor and told me they had a ‘European’ ancestor who I suspect was Armenian. The Armenians of Calcutta were often referred to as Turks by others as they had hailed from the Turkish empire where millions had once lived in eastern Turkey.

By the way, I was formerly from Malacca and have often visited the Christchurch when the old gravestone of Jacob Shamier is at the entrance. Once in 1968, I saw two gentleman tracing the gravestone’s script and emblems on a large white paper. They told us they were Armenians from New York and asked us if we knew where Armenia was. I told him it could somewhere near Russia.

There are still several Armenian gravestones, several centuries old in the ruined church on St. Paul’s Hill next to the Christchurch.

There are no Armenian gravestones in the old Church ruins on St Paul’s Hill. I had heard this rumour and checked it out.

Mymensingh is in the present Bangladesh and formerly East Pakistan.

Hi Nadia,

My late Grandmother’s family was from Armenia, but as she was orphaned at age 2, we’re totally in the dark in regards other family. While doing some research, I came across this article. The gentleman you mention here, Jacob Shamier, is my Grandmother’s great great Grandfather.

The family originally came from Julfa, in Armenia. They then settled in Persia, then India, next Malacca and finally Indonesia. Over several centuries though.

So thank you for your informative article and adding another piece to the puzzle.

Thank you for adding that information Jobu.