For years, I’ve eyed my mother’s recipe cabinet longingly. Brimming with books slung together in no particular rhyme or reason, it occupies two giant floor cupboards in my parents’ kitchen. I have hoped to one day muster up the patience to give it a thorough cleaning. Last September, I was in between jobs. I had some down time.

For years, I’ve eyed my mother’s recipe cabinet longingly. Brimming with books slung together in no particular rhyme or reason, it occupies two giant floor cupboards in my parents’ kitchen. I have hoped to one day muster up the patience to give it a thorough cleaning. Last September, I was in between jobs. I had some down time.

Having come to the United States as a refugee from Soviet Armenia in the seventies, my mother’s journey of assimilation into American culture has required a great deal of trial and error. As I peeked inside her cupboards stacked with messy piles of books and gadgets, I came to realize how much of that could be understood through the paradigm of food.

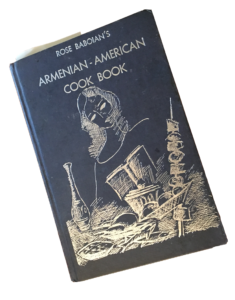

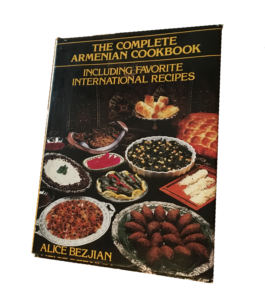

It’s no surprise that Armenian cookbooks are disproportionately represented in our recipe cabinet, which is home to legendary texts such as Rose Baboian’s Armenian-American Cookbook (1964), which made Western Armenian recipes, once learned by rote or passed down in a mother’s scrawl, accessible to an English-speaking generation; Alice Bezjian’s The Complete Armenian Cookbook (1995), so complete it isn’t even limited to Armenian food and includes Moroccan, Mexican, and even Japanese recipes; Linda Chirinian’s Secrets of Cooking: Armenian/Lebanese/Persian (1987); and even the surprising Armenian Vegan (2013) by Dikranouhi Kirazian. My mother had her own Armenian recipes, of course, and even kept tucked away a small notebook full of them, handwritten in her mother’s Armenian script. But these were familiar. Armenian recipes were useful for reference, but didn’t quite offer a new vocabulary to my mother’s culinary lexicon.

Easy Entertaining’s menu for Memorial Day Weekend, for example, suggests a hot artichoke dip, grilled chicken breasts, beer and soda, and instructions to stop by the local veterans’ hospital to thank them for their service or “inquire about volunteer opportunities.”

We lived in an affluent suburb of Washington, D.C., yet while Northern Virginia is a progressive area where diversity is welcomed, at least in my adolescent experience, assimilation was basically self-preservation. My mom cooked Armenian dishes like dolma, sarma, boregs, and traditional stews for us kids, but by our teens, my sister and I wanted to eat whatever Becca, Lauren, and Chrissy’s moms were serving, not the concoctions Araxie was cooking up that my classmates couldn’t pronounce. It didn’t help matters that we were children of the nineties to whom synthetic foods and flavors were shamelessly advertised. My mother yielded often to the will of corporate America as it expressed itself through her half-Armenian children’s food preferences. For better or worse, lunchables, Kool-Aid, and Fruit Roll-Ups were well-represented in my school lunches.

My sister and I took for granted our mother’s native fare, but our neighbors didn’t. In our cozy, suburban community, dinner party after dinner party established her as a celebrity for her Armenian cooking. In fact, it’s immediately clear from her recipe cabinet that the books most useful to my mother as a suburban homemaker were not the Armenian, but American cookbooks, which instruct readers on how to create and curate a uniquely American dining environment, with which she could infuse her ethnic flair.

My sister and I took for granted our mother’s native fare, but our neighbors didn’t. In our cozy, suburban community, dinner party after dinner party established her as a celebrity for her Armenian cooking. In fact, it’s immediately clear from her recipe cabinet that the books most useful to my mother as a suburban homemaker were not the Armenian, but American cookbooks, which instruct readers on how to create and curate a uniquely American dining environment, with which she could infuse her ethnic flair.

“Some people are put off by entertaining because they think they have to live in a large, beautiful house and have expensive china and sterling silver in order to ‘entertain,’” wrote one passage of Betty Crocker’s Easy Entertaining (1982), “Nothing could be farther from the truth!”

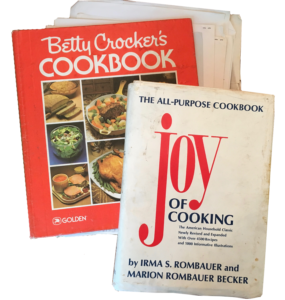

Books like Betty Crocker’s Cookbook—which single-handedly produced the entire menu for our Thanksgiving dinners—and the Joy of Cooking introduce one not simply to recipes, but to the art of entertaining, educating readers on the traditions associated with certain holidays, as well as customary menu items (or, at least, those its authors deem acceptable). Easy Entertaining’s menu for Memorial Day Weekend, for example, suggests a hot artichoke dip, grilled chicken breasts, beer and soda, and instructions to stop by the local veterans’ hospital to thank them for their service or “inquire about volunteer opportunities.” All the while, a motivational tone is present, offering frequent words of encouragement for fledgling hosts.

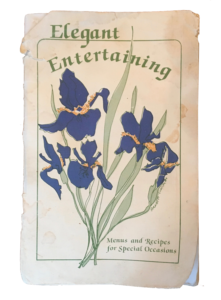

One stood out amongst the books in this genre. Elegant Entertaining: Menus and Recipes for Special Occasions was just 36 pages long, yet its binding was worn and stained. Authored by two women from Pennsylvania with no reference to a publishing year, this no-nonsense little pamphlet was devoid of cultural commentary, but my mother confirmed its calligraphed recipes made for outstanding, time-tested classics. She has since mastered many, like the Potato Rounds (pg. 20) and Salmon Filet (pg. 7).

“To entertain friends at home is the nicest way to say they’re special,” goes the short, two-sentence preface to the book. “These recipes and menu ideas will help you do so with ease… and a bit of elegance.”

“To entertain friends at home is the nicest way to say they’re special,” goes the short, two-sentence preface to the book. “These recipes and menu ideas will help you do so with ease… and a bit of elegance.”

My mother’s search to understand the authentic American experience often brought us to where it all started—Colonial Williamsburg. During our family vacations to the area, she purchased several cookbooks. To be honest, she never uses them, but they add to the eclectic patchwork of culinary interests that is her recipe cabinet. Shepherd’s Pie, an old, Anglo-saxon staple, was always a beloved family favorite in our home, and Betty Crocker‘s recipe served us just fine.

But it wasn’t the colonial influence that drew my mother and so many other immigrants to this country; it was the multiculturalism. Armenia had been a homogenous country, unwelcoming to outsiders, which she and her family were. Though they were Armenian, they had only come from Romania to the Soviet Union in the forties. They were part of an entire demographic of citizens who were discriminated against from the outset, and referred to by the slang word, aghpar. My mother, traumatized by that experience, has spent a lifetime celebrating the openness this country represents, introducing the culinary contributions of countless other immigrant communities to our dinner table. German Schnitzel, Polish Perogies, and Irish corned beef were all dishes we ate regularly.

Quick, easy, and straightforward meals, like pizza, spaghetti, and burgers (though her patties always had a kufte-like taste to them), were also staples in our family. Like many suburban households, we were always on the go—hopping from piano lessons, to basketball and then soccer practice. There were even times when our fast-paced lifestyle left my mother, who worked full-time at the State Department, no time for cooking at all.

Quick, easy, and straightforward meals, like pizza, spaghetti, and burgers (though her patties always had a kufte-like taste to them), were also staples in our family. Like many suburban households, we were always on the go—hopping from piano lessons, to basketball and then soccer practice. There were even times when our fast-paced lifestyle left my mother, who worked full-time at the State Department, no time for cooking at all.

After an hour of sorting, I looked at the pile of discards, which contained: the droves and droves of celebrity and fad diet books—it wouldn’t be a suburban household without them, though they never yielded anything tasty—as well as the countless manuals to now-long-gone gadgets that at one point promised to make food-preparation faster or easier or healthier—bread-baking machines, smoothie and yogurt-makers, grinders, blenders—but had all either lost their fashionable appeal or ability to work.

My mother flurried about in the kitchen, amused, as I messily stacked books in piles according to relevance and genre. Occasionally, she’d comment on certain ones and particularly successful recipes they contained. She beamed at the suggestion that I take some with me to my new apartment, and I excitedly set about earmarking recipes I intended to try on my own. “It’s too much work to make it yourself,” she casually remarked when I asked for advice on preparing a Thanksgiving menu one day in the future, “It’s easier to just buy the stuff ready-made.”

My mother flurried about in the kitchen, amused, as I messily stacked books in piles according to relevance and genre. Occasionally, she’d comment on certain ones and particularly successful recipes they contained. She beamed at the suggestion that I take some with me to my new apartment, and I excitedly set about earmarking recipes I intended to try on my own. “It’s too much work to make it yourself,” she casually remarked when I asked for advice on preparing a Thanksgiving menu one day in the future, “It’s easier to just buy the stuff ready-made.”

It’s odd to consider that as hard as my mother worked on the meals of my childhood, I was rarely, if ever, invited to assist in preparing them. She preferred I spend that time practicing piano, playing sports, doing homework, or out with friends; fitting into this American life, as it were, on her behalf.

Unfortunately, our traditional foods have been stolen by the Turks and are now passing them off as “Turkish Cuisine”. This was possible of course due to the success of the Armenian Genocide, and now the artificially large nation they are occupying as a result of that Genocide combined with their sheer numbers makes it hard to keep their lies in check. To make matters worse, they have ignorant western “scholars” on their side pushing their cultural fairy tales. Even more difficult, many old Armenian names for our dishes have been lost as a result of most Armenians in the Ottoman empire speaking only the language of the empire, Turkish. Even though I am certain that with proper research, much of Turkish words can be shown to be of Armenian origin.

Up til now, our scholars, researchers and academics have ignored this field of study to the detriment of our culture and history. It’s quite sad, really. The western ignorant masses have no desire to hear about what is stolen from where, as they would only care about what they are being fed. I wish that the academics and scholars in Armenia would establish some kind of cultural research union to establish all our historic cultural foods from every province of our historic country, and to specifically expose all the fraud and lies from Turkey and Azerbaijan regarding their so-called cuisines.

When two women get together they say “Oh you have this in your culture, how nice I have something very similar in my culture.” These recipes were shared between neighbors, they are not Turkish or Armenian, but Ottoman. The only one lying is you, to a Diaspora too ignorant of their own history to do anything but follow blindly the Piper to War (and give their American money to the Righteous Cause no doubt). You are disgusting.