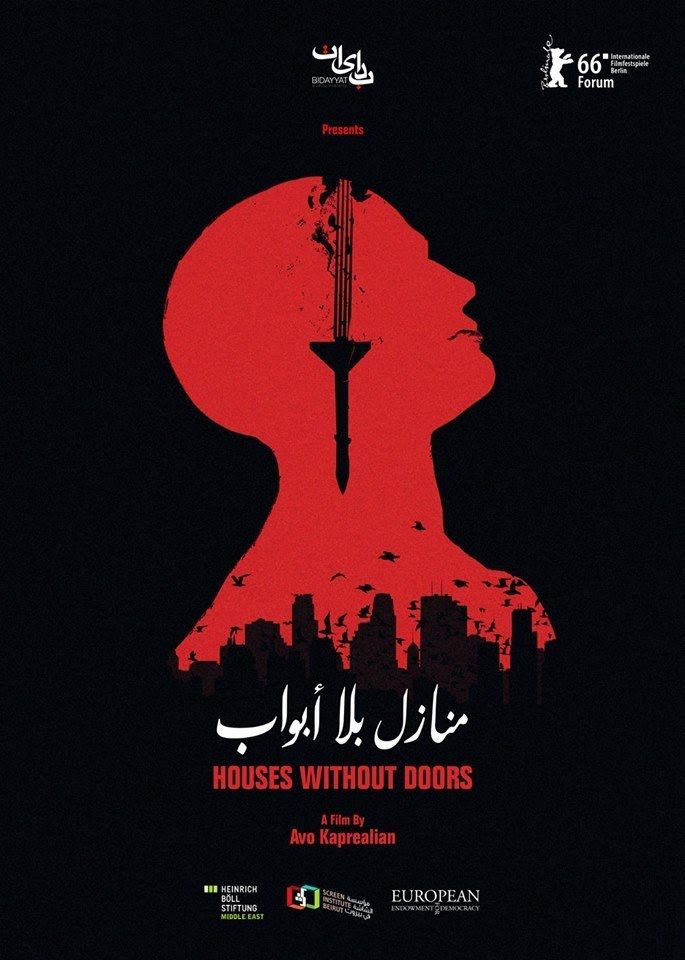

A Film Review

Special for the Armenian Weekly

“Houses without Doors” (Syria, Lebanon)

2016, color, 1:28

In Armenian, Arabic, French, and Spanish, with English subtitles

Director: Avo Kaprealian

Producer: Bidayyat & A. Kaprealian

Distributor: Bidayyat Productions

What is the difference between a feature film and a documentary? A feature has a cast of actors playing roles in a scripted story; a documentary has a sketchy story line and presents research about issues in the lives of real people. One might say that Avo Kaprealian’s film “Houses without Doors” is a bit of both. His earlier short films also belong to the same pattern of not fitting into a classic genre, while also pulling archival footage into his work.

The starting scene is a collection of military parades, but the film’s message is nothing if not about peace. Next to Avo’s apartment, in front of the church in the Armenian neighborhood of Aleppo, people chant joyful hymns for a wedding, and line up their cars to parade in the streets; then, on another day, they line up again, this time for the funeral of a young lady who had fallen victim to a midnight shelling.

The film is a bitter painting that depicts the demise of the once-thriving Armenian community of Aleppo, which was formed in the Middle Ages and became the beating heart of the Armenian Diaspora after the genocide in 1915 by the Ottoman Turks. The land that was a safe haven for a majority of Armenian refugees and survivors 100 years ago is being brutally devastated; its once-welcoming people are left uprooted and miserable. The life of the community is a microcosm of the larger Syrian society, with repeated experiences from a century ago. This is a dramatic story of death, exile, and survival.

Avo himself is of Syrian-Armenian heritage, a fact that is clearly seen in this film, especially by the influence of the legends of Armenian cinema, like Artavazd Peleshyan and Don Askaryan. Viewers get glimpses of Syrian life under the circumstances of war at home and in displacement. Children at home play run-and-catch as “regime vs. opposition,” while displaced children talk about their dreams, about having a pet and going to school. The life of citizens under the circumstances of war and deprivation is depicted carefully by the queues for bread, and babies in strollers watching missiles in the sky. Each scene is put in front of a mirror from the past, recounting old stories from films like “Mayrig” by Henri Verneuil, which talks about the Armenian Genocide and the experiences of the refugees. While the voice of one death march survivor from “Mayrig” tells the anguish that befell father Serovpé (the priest of his village), in the matching scene a Syrian hajji is wandering near the checkpoints. Another scene, again from “Mayrig,” where the death marcher has his foot mercilessly nailed with a horseshoe by Turkish gendarmerie, is followed by archival footage of Sultan Abdul Hamid, infamous for his tyranny and bloodthirstiness. The perfect sequence of the scenes, as well as the consonance of audio and visual materials matched from different films, create a perfectly intertwined story that is difficult to tell with words. This is where cinema serves as an instrument of memory and transmits its message to the future.

Avo’s main character in the film is his mother Lena, who eventually packs everything up and leaves her home along with the entire family to Lebanon. The credit of the name of this film goes to her. Dreams can have very peculiar interpretations. In Lena’s dream, when she sees her Aleppo home without doors to lead her inside, she understands that there will be no return. She was going through the same painful journey that her ancestors were forced to take 100 years ago from Western Armenia. The film offers an intimate picture of an Armenian family’s daily life in Aleppo, with such genre scenes as religious services, festive processions, birth, funeral, family gatherings, and private conversations. It is an excellent historical document.

On a technical basis, the film is well done. The scenes are nicely structured and suggest that Lena, unlike her husband, is extremely comfortable with the omnipresent camera of her son. The subtitles are clear.

Avo poses multiple questions in “Houses without Doors.” However, perhaps the most pressing issue might be the thin line between justice and revenge. In one scene he shows Syrian civil activist Mohamed Abdul Wahab beaten up and uttering his famous sentence on camera—“I’m a human, not an animal, and all these people are like me”—which became a motto for revolting Syrians. Mohamed turned into a militant in a rebel group and was reportedly killed a couple of years ago. Avo also uses archival footage to tell the story of how Soghomon Tehlirian, an Armenian Genocide survivor, brought justice for 1.5 million victims by gunning down the mastermind of that Crime, Talat Pasha of the Young Turk government, in daylight Berlin. Avo’s film is not an attempt to describe a remedy to achieve justice, but he doesn’t shy away from voicing his own views about it. In the end credits, he dedicates the film to the memory of Soghomon Tehlirian.

Ultimately, although touching upon political issues that involve Syria, Turkey, and Armenia, Avo’s critical approach as an artist has made the film unable to be utilized politically by almost any willing party. This particular twist can make the film unpopular among many circles, but that in itself is a confirmation of the director’s talent, passion, and candidness.

The international premiere of “Houses without Doors” took place on Sat., Feb. 12, at the Berlinale International Film Festival 2016 in the Academy of Arts (Akademie der Künste) of Berlin, Germany.

I am anxious to read/see/own this artful/deliberate portrayal of our people who have suffered the barbaric treatment led by the powerful, and cunningly enlisted many of their own people to degrade themselves.