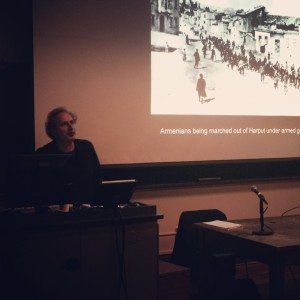

NEW YORK—On Wed., Dec. 4, the Armenian Center at Columbia University hosted a symposium on survivor meaning featuring reputable leaders in the field of study, including Peter Balakian, Jay Lifton, and Marianne Hirsch. Titled “Survivor Meaning: After the Armenian Genocide, the Holocaust, and Hiroshima,” the panel delved into the experience of survivors as they searched for an understanding of their tragic experiences.

Acclaimed poet and prize-winning author, Balakian was introduced by Marianne Hirsch, the William Peterfield Trent Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, who served as the moderator of the panel and who has written several important books on trauma and memory and the Holocaust.

Balakian presented a personal and inherited familial narrative—the case of his grandmother Nafina, a survivor of the Armenian Genocide—as a “way of engaging conversation in survivor experience.”

A resident of Diyarbakir/Dikranagerd during the genocide, her family’s homes and properties were looted and confiscated, and she was witness to the massacre of her family and community. Nafina survived a forced march, in which everyone in her family was killed.

Having arrived in Aleppo in the fall of 1915, she began to compile affidavits for what would be a human rights suit against the Turkish government for all the losses endured by her family. Balakian read his grandmother’s insurance claim from his New York Times bestselling memoir, Black Dog of Fate. He said the claim, which she filed when she arrived in the United States, “contributed to the understanding of a survivor in the immediate aftermath of an enormous encounter with mass killing, rape, starvation, famine, and death.”

“She was witness to the truth,” said Balakian, who is the Donald M. and Constance H. Rebar Professor of the Humanities at Colgate University and the Ordjanian Visiting Professor in Armenian Studies at Columbia University.

Scholar, psychiatrist, and historian Robert Jay Lifton, who has written more than 20 books on trauma, survival, and violence, defined a survivor as someone who has in some way encountered death, witnessed it, and at the same time remained alive.

“There’s a triumph in surviving because one stays alive,” said Lifton, Distinguished Professor Emeritus at CUNY/Graduate Center and John Jay College for Criminal Justice. “It’s necessary to give meaning to that catastrophe if one is to find meaning in the rest of one’s life.”

He said survivors of the bombing in Hiroshima, Japan, after World War II experienced a lifetime of “death-haunted imagery” from both the encounter itself and the effects of the tragedy that carried over to the next generation.

“From survivor meaning comes a survivor mission which one carries out in order to assert that meaning,” said Lifton, who concluded his presentation by returning to Nefina’s story. “There was a heroic struggle by this woman who sought to oppose the forces of destruction in her life. I don’t think there could be a better moral principle in which to base our world.”

Following Balakian and Lifton’s presentations, Hirsch posed follow-up questions, including why Nafina “chose a legal claim, not to seek repair but to voice the wrong and to commemorate the dead.”

“It’s a stay against being expunged or annihilated,” said Balakian, who remarked that nothing came of the claim and that the document remained in a dresser drawer for 60 years until he found it. “In cases of mass killings and genocides, the survivors end up taking the ethical role, and family is essential. This claim has a graveyard dimension to it.”

Nafina experienced the catastrophe and retold the story through the means of her legal claim, Lifton said. “What is unsuccessful in a legal sense starts legal ramifications of the witness, and there’s something moving about that.”

He noted that calamities like the Holocaust, Hiroshima, and the Armenian Genocide annihilate meaning along with human beings and structures.

“As human beings, we are meaning-hungry creatures,” said Lifton. “That’s why the struggle for meaning is so difficult and poignant and painful. But it always goes on because that’s how we function mentally. We must recreate all that we perceive.”

Peter Bakalian is a such a knowledgeable scholar and historian. All of my great-grandparents were survivors of the Armenian Genocide; it took not only them, but also, me, a while to find meaning as to their survival in the Genocide.

Peter Balakian you are truly a great Armenian. Thank you for helping me understand the plight of my grandparents and my Armenian people. In my family they never spoke of horrors that they experienced. My Grandparents loved their life living in America. As 1915 soon approaches, how do we stay silent !

Thank you Taleen for your coverage of the pertinent points of the talk. A lot of us survivors, children and grandchildren of Genocide survivors, suffer from a form of PTSD which has been shown to be transmitted through generations. Studies done on Holocaust survivors has shown this to be the case. Those who take action (telling their stories or writing about them) are trying to heal themselves. Those who remain silent are actually are manifesting and suffering some of the symptoms of PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder).