A long time ago, the Baathist Syrian government swiftly placed the iron noose around cultural institutions and nationalized them. I must have been 14 years old when I woke up one morning and found the Cinema Orient (Cinema al-Sharq) moniker covered with a white canvas that read, in red Arabic letters, Cinema al-Kindi. I’d never heard of al-Kindi before and the Arabic script could’ve read the Kennedy Cinema or al-Kanady (meaning Canadian) Cinema. What a paradox, I thought, for a pro-Soviet socialist government to borrow such western names.

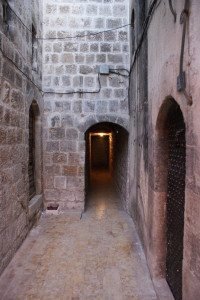

The queen of Aleppo’s cinemas was located on al-Khandaq Street, a thoroughfare crowded with coffee shops, restaurants, photo studios, bookstores, nightclubs, and cabarets like the Moulin Rouge, Madam Lucy’s, and the posh Basheer Restaurant Français, a leftover from the French colonial mandate where the staff had to speak a minimum of four languages. Al-Kindi had a spacious hall on the ground level and a large second level al Balcon or the Lodge that expanded in midair over half of the seats below. Huge wooden panels punctuated by light ornaments crawled up to the plafond, from which a massive crystal chandelier hung down. Red and blue neon lights framed the luscious velvet maroon curtain that covered the gigantic silver window onto the world. Between the salon and the balcony was a cafe that served espresso, hot chocolate, brioches, sweets, and candy bars.

Aleppo’s attired and orderly audience would arrive ahead of time to enjoy a beverage at the cafe before finding the numerated seat inside the theatre marked on the ticket with a red wax pencil. A loop of “La Comparsita” performed on the accordion played in the background until the house lights fainted and the velvet curtains parted like the Bible’s red sea. The neon lights dimmed before the “coming soon” trailers flashed on the screen. This grandiose overture marked the al-Kindi cinema from the Ugarit, Aleppo, al-Zahra, al-Hamra, Opera, Roxi, al-Dunya, Royal, al-Suriya, Rio, and other cinemas that were within a walking distance from each other. Almost all showed class A-American films, but the one with a cafe serving hot chocolate was the best.

Days later, I learned from Mr. Yahya, my civics instruction teacher, who was the Ministry of Culture’s provincial office director in Aleppo, that al-Kindi was an Iraqi Arab known as the world’s first ophthalmologist. The cinema was named after him in part as an attempt to Arabize it. He pronounced that from then on, the screening would be drawn to fit a new national educational scheme, and that the Ministry of Culture had established Nadi al-Cinema (the Cinéma-Club), a new association aimed to attract professionals (physicians, architects, lawyers, university students, and the diplomatic crops). Clubs were established in Damascus and Aleppo, and members could watch a selection of films during the 9 p.m. Saturday slot at Cinema al-Kindi, the only nationalized cinema; the other movie theatres remained privately owned but received their films from the central office in Damascus.

The supply of films that fit within the new scheme fell short of expectations; to keep the screens busy, carefully selected old prints like “On the Waterfront,” “Mogambo,” “A Streetcar Named Desire,” “The Train,” “The Bicycle Thief,” “Shoeshine,” “La Terra Trema,” to name a few, reappeared. We became familiar with Carl Malden, Marlon Brando, Richard Harris, Silvana Mangano, Burt Lancaster, Sophia Loren, Alain Delon, Joseph Cotten, John Wayne, Orson Wells, Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole, Anthony Quail, Anthony Quinn, Kirk Douglass, Stefania Sandrelli, and a slew of others, until Eastern European, Soviet social realism, spaghetti westerns, Arabic, and Indian films found their way to our eyes. The best of the “art films” were left for the Nadi al-Cinema members. The films I eagerly wanted to see were reserved for the “elite,” while the rest of the population, enduring the Baathist slogan “Wahda Houriya wa Ishtirakiya” (Unity Freedom, and Socialism, the Arabic of which means partnership or sharing) were served exclusively with second- or third-rate commercial films. For days and weeks I knocked on the door of the Cinema Club director until I was able to convince him that I deserved membership based on my knowledge and love for cinema, despite the fact that my age disqualified me from applying. After three months of haggling, I was asked to deliver a photo for a membership. The next day I filled out the form, handed in my photo, signed the document, and was given the card with a lapel copper pin. I pierced it proudly on the collar of the jacket I was wearing on that rainy day, and went to my Karen Jeppé Armenian High School boasting my achievement.

During recess, Mr. Kh., the superintendent, noticed the attention my pin was earning among my classmates. He walked closer to me with a predisposed negative attitude and asked what I carried on my jacket. When I explained, he slapped me harshly and said how careless I had been about my Armenian heritage by joining an Arab organization, being assimilated through this worthless form of entertainment called cinema, and how I ought to use my brain for more worthwhile endeavors. Rebellious, my teenage temper exploded. Bravely I retorted, “You don’t have the brain to understand what this pin means to me! Check with the Ministry of Culture if I’ve done anything wrong!” I was instantly suspended from classes for three days. Years later, he moved to Los Angeles, and I was at the UCLA film department while heading the Armenian Horizon TV show. He visited me in my Glendale office and asked what was I up to, besides my TV work that made him proud. When I told him that I was completing my cinema studies, he replied, “You haven’t given up on that stupid field!” Instantly I asked him to leave my office.

Less than a few weeks after my admittance to the Nadi al-Cinema, my classmates Vahé S., Hovig N., Hratch N., Garo K., Hrant P., Kevork D.V., Sarkis Gh., Levon B., Hrair K., and many others, who have all emigrated from Syria since then, followed. Every Saturday at 9 p.m., we watched films like “Memories of Underdevelopment,” “Is Paris Burning?” “Satyricon,” “Borsalino,” “Oedipus Rex,” “Children of Paradise,” “King Lear,” “I’m Cuba,” “The Cranes Are Flying,” “Ashes and Diamonds,” “Kanal,” “Birchwood,” “Cleo in the Afternoon,” “Claire’s Knee,” “L’Aventura,” “The Red Desert,” “The Gospel According to Saint Mathew,” “The Working Class Goes to Heaven,” “Sacco and Vanzetti,” “Au Hasard Baltazar,” “Pick-Pocket,” “Les Diaboliques,” “Juliet of Spirits,” “Behold a Pale Horse,” “A Man and a Woman,” “Le Passager de la Pluie,” “Before the Revolution,” “War and Peace,” “The Trial,” “Citizen Kane,” “Porcile,” “Taras Bulba,” “Umberto D,” “400 Blows,” “The Battle of Algiers,” and other strange, beautiful, old and new films.

Most distinctly, I remember the night I watched the Cuban film “Lucia.” The organizers had prepared a handout with information on the film and the filmmaker, Humberto Solas. I volunteered to distribute the single-sheet flyer to the audience. When the lights dimmed, I handed the remaining sheets to the elderly tall and husky ticket controller, whom I had befriended, and ran to take my seat. “Lucia,” a black-and-white, three-hour masterpiece depicting the history of Cuba, was a compelling experience. Unfortunately, there was no post-screening discussion to learn why I liked a film that looked and sounded so different from all the others. I was overwhelmed with the majesty of “Lucia” and couldn’t stop talking about it even when my father scolded me for staying up late—learning from films instead of textbooks. Besides the sacred Saturday night screenings, Nadi al-Cinema programmed Polish, Bulgarian, and Soviet film weeks. I attended every single one of them until I left Syria, when the October war of 1973 unleashed hell on everyone. By September 1972, my father had gone to the U.S., successfully converted his tourist visa to immigrant status, and sent for us. At the outbreak of the war, we left for Beirut, where a few months later we obtained our immigration documents from the American Embassy and flew to Boston on January 1974, leaving behind abundance to recall. After graduating from South Boston High School, I moved to New York City to study cinema at the School of Visual Arts. In 1982, I received my bachelor’s degree in cinema and went on to UCLA’s graduate film school for a master of fine arts.

I signed up with Teshome Gabriel, who was teaching a course titled “Film and Social Change” about emerging cinema from the third-world. As he distributed the course’s syllabus, my classmates were in shock at the titles, the filmmakers’ names and their countries of origin, but I felt perfectly at ease, as I had seen most of them at Cinema al-Kindi. My challenge now was now to see these films as an adult.

One day he announced we were going to watch a three-hour long Cuban film and that we ought to be prepared for it. Before he could utter the title, I asked him if it was “Lucia.” He was surprised and asked how I knew about it. I replied that I had seen it years ago in Aleppo; I further commented that it was way ahead of Andre Konchalovsky’s “Siberiad,” which depicted the Russian/Soviet centennial and Bernardo Bertoluchi narrating Italy’s last century. An interesting discussion ensued until he mentioned Syrian filmmaker Nabil Maleh and his brilliant film “Al Fahd” (The Leopard). I asked if he had seen the Italian film “L’Amante di Graminia” starring Stefania Sandrelli and Gian-Maria Volonte, which inspired the The Leopard. He had not, and we joked about who was going to teach who.

Jersy Antczak, a Polish filmmaker, joined the UCLA film department in 1985. The short fellow with strikingly premature white hair was a dynamic man who thought us directing with the camera instead of through actors, dialogue, lights, props, or music. When we met for the first time, he wanted to interview students before accepting them into his class. I realized that I had seen one of his films in the al-Kindi cinema in the framework of Polish cinema. Most of the filmmakers were invited to attend and present their films to the audience with the comical absence of translators. He smiled in his unpolished heavy Polish accent and said, “I vil tel to yu sumtting, van of the Polish men vitout translator in Damascus and Aleppo vas me!” The formality of student/teacher vanished at once as it had with Teshome. Jerzy taught us how “organic camera movement” can be a director’s supreme tool.

In 1999, I visited Aleppo for the first time since my departure in 1974. I quickly went to visit the cinemas that were still there, but none were as they used to be. Not a single one was screening a decent or a recent film, proposing instead F-class films like “Turkish Hamam” or “Women’s Jail,” featuring exposed female flesh. The population of the city had changed drastically and downgraded. Cheap kiosks, sandwich shops, and vendors selling pirated CD and audiocassettes had replaced all the high-profile restaurants, cafes and bars. The streets were garbage-laden and al-Kindi’s facade panels carried posters of old Egyptian films, while stills of half-naked chubby women fighting each other with long finger nails, their nipples and bottoms blackened with black ink, adorned the creepy entrance. Socialist Syria’s mission had degenerated to lower depths. None of the cinemas where I had spent my youth fulfilling my love of the seventh art could stand witness to those glorious days now gone for good. With tearful eyes and much loathing, I observed the government’s neglect of culture. The aging regime had shipped the learned Aleppo population back to illiteracy. The city’s wealthy cinematic and cultural heritage, which once hosted Pierre Paolo Pasolini and Maria Callas to film “Medea,” and the Nadi al-Cinema, my source of pride at UCLA, were forever relegated to my memory, while I made one last effort to learn about the origin of al-Kindi.

Abu Yusuf Y’aqub ibn Ishaq ibn Sabbah ibn Omran ibn Isma’il al Kindi was born in Iraq, hailing from the Yemenite Kindi tribe. Although known as a Muslim scholar, every single one of his names suggests a Jewish heritage: Yusuf is Joseph, Ya’qub is Jacob, Ishaq is Isaac, Omran is the same, and Isma’il is Ishmael. I guessed he must have converted to Islam without changing his name. Al-Kindi (801-873) was known to be the first peripatetic Arab-Islamic philosopher with 240 books to his credit, ranging in philosophy, astrology, cosmology, chemistry, cryptography, mathematics, medicine, music theory, and optics. His was a giant mind that introduced Greece’s scholarship to Islam. His later rivals, al-Farabi and Ibn Sina (Avicenna), belittled his accomplishments.

With the Islamic revolution in Iran, the new government established a state-run centralized cinema foundation called al-Farabi. There is a sinister irony to the idea that pan-Arab nationalist, socialist Syria uses al-Kindi and the conservative Islamic Republic of Iran uses al-Farabi—two rival scholars who lived in Aleppo—to oppress filmmakers, while they represent two of the brightest and most enlightened minds of Muslim scholarship in the 9th century and beyond.

“La Comparsita” remains engraved in my memory from the years of frequenting al-Kindi; it found its way to the opening sequence of my film “Chickpeas” as the only non-original music. Unfortunately it didn’t catch the attention of any journalist or film critic who interviewed me around the world. Had anyone asked…

And so it goes.

What a beautiful piece, Mr. Bezjian! I was born and raised in Aleppo too, my guess is that we are close in age (per IMDB). I remember al-Kindi all too well. In fact I remember also seeing some Robert Altman, Charlie Chaplin and other movies over there.

In any case, now I am curious to see your movie, Chickpeas. I’ll be looking for it.

Best, Fuad

Nigol, very interesting on how you are reviving the past in details, as i read , i am living with them, and i do remember those Al-Kindi club movie nights, and how we would get out and do our own critics.

Another lovely memoire, Baron Bezjian. Maybe someday you’ll make a film about it. :-)

Fascinating article. I was born and grew up in Iran, now live in the U.S. but so many things in your narrative brought back memories of my growing up years, and some of the cultural similarities, and differences, of us Armenians living in friendly Middle Eastern countries.

I already e-mailed your article to several people.

I’ll now look for Chickpeas.

Thank you dear Fuad. CHICKPEAS is sold in USA on VHS.

Parev Nigol aghpar : Skanchelli paner kradz es Halebi masin.Yes al koo hedet Haygazian katzadz em(dghotz pajin,jidadeh.1968). Urakh em te amen pan lav untanum eh kez hamar. Lav Maghtanknerov Vicken Derderian . ( Toronto)

Dr. Vicken. Just last week Matig Eblighatian and I went to the street on which you lived and remembered you so well…

Hi Nigol nice to hear from you. few classmates are in toronto : Sarkis Ghazelian,Kourken Mangasarian. Anto Hotoyan . Raffi Mirzoyan & Apkar arzoumanian live in Montreal.

Good luck cary on brother. Matogin Parevner