LA Times War Correspondent Talks about Kosovo and ‘Promised Virgins’

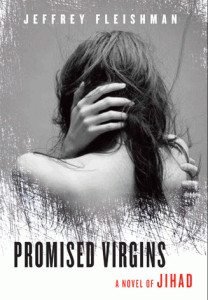

WATERTOWN, Mass. (A.W.)—On May 14, Jeffrey Fleishman, the Los Angeles Times Cairo Bureau chief and former Philadelphia Inquirer war correspondent assigned to the war in Kosovo from 1999-2000, spoke to the Weekly about his debut novel Promised Virgins: A Novel of Jihad (Arcade Publishing, February 2009) set during that war, and his experience covering it as a journalist.

“I tried to make it say something that was unique in a new way,” said Fleishman about the novel and the sense of authenticity it brings readers of war correspondent culture and interactions. “There are scenes in the novel in which the seed or root of a character has been drawn from a composite of my experiences with other journalists over the years.”

Asked how autobiographical the novel is in its narrative and portrayal of the protagonist, war correspondent Jay Morgan, Fleishman said, “Well, there’s one mention of a trek across the Himalayas with Tibetan monks, and I actually did that.”

Of one of the novel’s most emotional scenes, which occurs in Beirut, Lebanon during the civil war there, Fleishman said, “I have been to Beirut but I didn’t cover it during the civil war. I covered the Pope’s visit there in 1997. He delivered his speech from the shore of a beach that had been extended using ground up buildings and wreckage from the war, and the impact of that has never left me.”

Fleishman spoke to the novel’s driving notion of Islamic fundamentalists crossing the border into Kosovo during the war to recruit suicide bombers from the Balkans in the lead up to September 11. “There were some guys who came in from the U.A.E. during the war before NATO got there who tried to radicalize the KLA [Kosovo Liberation Army] and the local Albanian Muslim populations, but it never really took hold there. The Kosovar Albanians are too European.”

He recounted of the war, “I remember an occasion talking to a Serbian judge in his courtroom about the subject. He had maps and showed me the location of where some of these U.A.E. radicals were in the mountains. The Serbs were actually hoping to use their presence as a propaganda strategy in their favor. But they [the fundamentalists] were never there to the level fictionalized in the book.”

The KLA has since been integrated into the Kosovo government as the Kosovo Security Forces (KSF). Fleishman spoke to me about his interactions with their fighters and commanders. “They were an interesting strand. A lot of the fighters and money of the KLA came from Europe from the Albanian Diaspora in Switzerland. Another journalist I was with deemed Kosovo the ‘Waiter War’ because so many KLA fighters had been waiters in Switzerland and Belgium when the war broke out.”

“I remember a meeting in Geneva, by Lake Geneva, to meet an Albanian businessman and interview him about those that were sending money to the KLA in the diaspora,” he said. “It was surreal because there were all these blonde-headed little Swiss children playing around us and here we were talking about gunrunning and money to fund a guerrilla war.”

Yet, what is greatly exaggerated, he said, is the notion that the KLA was all funded by Albanian drug money. “Much of the money simply came from the Albanian Diaspora. But this changed when many of the Kosovar Albanians crossed into northern Albania. … Suddenly there wasn’t the same sense of the solidarity and friendship. Kosovar Albanians and Albanians from Albanians are very different kinds of people,” he noted, of the Kosovar refugee crisis that flooded the Balkans and southern Europe after the war ended.

“Kosovo, everyone figured, would be the bookend of the Balkan crisis that occurred in Bosnia,” he said of the war’s origins. “You knew it was going to happen. I was there in ‘98 and I remember that the KLA were these very young guerrillas.”

“After one uprising, it livened and regenerated the young that ‘We can’t do it the Rugova way anymore.’ And it mythologized the KLA in the minds of the people.”

He explained, “It was a very weird war. Within 18 months you had an uprising, a rebellion, a guerrilla war, and a NATO intervention bombing campaign, followed by a refugee crisis. It was just all these torrents of history, but in such a small period of time.”

He agreed with the notion that Kosovo could be deemed the first “Sound Byte War.”

There’s widespread support today among many young Kosovars for the U.S.’s role in Kosovo’s reconstruction and independence, yet there’s frustration as well over the feeling that Kosovo exists as a U.S. political pawn and client state. “As soon as the war was over you had a very strong love affair with the U.S.,” Fleishman said, “whose soldiers were viewed as liberators by the Albanians, which was the complete opposite of what happened in the Iraq war where within days U.S. soldiers were viewed as occupiers.”

He continued, “In Kosovo there was this euphoria about U.S. involvement, with people throwing flowers as the NATO tanks rolled in—even the German ones, which was a little bizarre to see. … Parts of the KLA and the nationalists used this period to regroup and start up small-scale attacks against the Serbs still living in Kosovo.”

But, Fleishman said, “What people didn’t seem to understand is that it was really all to do with Milosevic’s manipulations. He went from being a communist banker to a leader that found the power of Serb nationalism and then exploited it.”

NATO’s intervention in the conflict was, according to Fleishman, a way of making right its hesitant interventionism in the previous genocide, which took the lives of roughly 32,723 civilians during the Bosnian War.

Of Bosnia’s impact on the outcome of the Kosovo war at the time, Fleishman said, “It’s amazing what a TV image can do. The international community didn’t want the same thing in Kosovo as in Bosnia and knew Milosevic was getting more and more volatile after he flooded the Macedonian border with [Kosovar Albanian] refugees. Europe also learned a lot between Bosnia and Kosovo when it came to ethnic cleansing: ‘Let’s get in there and stop this while we can.’”

Of the Armenian claim that the 2007 independence of the Republic of Kosovo sets an international precedent for the legitimacy of the Nagorno-Karabagh Republic, Fleishman stated, “I think Kosovo has drawn that blueprint that if you are an oppressed majority in a troubled enclave, you could end up with that prize of government. The question is, ‘Are we [the U.S. and international community] interested in redrawing maps right now?’”

Fleishman also talked about his reporting from Cairo, and of Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s January walkout from the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in protest of Israel’s Gaza assault on Palestinians. “People here [in Egypt] are dying for a strongman. They haven’t had that since [Gamal Abdel] Nasser. What Erdogan did at Davos was a major PR coup in favor of Turkey in the Egyptian press. Unfortunately, you have a country here that technically is still under emergency martial law [sporadically since the Mubarak government took power in 1981], while having this democratic veneer.”

I asked if he foresaw any changes in U.S. Middle East policy with the new administration. Fleishman stated, “I think Obama’s strategy is still being worked out but I think there is a change of tenor in Egypt that’s looking to occur and the Egyptian people are thrilled that he’s coming to address Cairo soon. But there will also be many disappointed people in the human rights community if he doesn’t bring up those problems in Egypt.”

Asked if he gave any credence to journalist and radio broadcaster David Barsamian and cyberpunk author William Gibson’s notion that oppressed peoples and enclaves could be globalized in their guerrilla campaigns by technology and were now no longer limited in their activism by geography, Fleishman responded that in the end geography is what really matters as a finite end.

“I suppose it’s possible, but when you print up the t-shirts for the revolution you don’t want a cyber logo on them, you want a real estate logo. And most people are still very concerned with real estate.”

Of his future projects, Fleishman said, “I’m working on another novel. It’s about memory, how we view it, and our relationship to it. I’m hoping to have it done this summer.”

Kosovo, everyone figured, would be the bookend of the Balkan crisis that occurred in Bosnia,” he said of the war’s origins. “You knew it was going to happen. I was there in ‘98 and I remember that the KLA were these very young guerrillas . Thats funny because the state department stated that the kla were terrorists in1998,so what were you doing with terrorists mr Fleishman?The Un and even US generals such as Charles Boyd,stated that the albanian exodus started after the nato bombing started,so the “humanitarian war” rally cry is a lie.No matter how you try to paint it,nato’s actions were by world law criminal. Its also incredible that you say milosevic’s manipulations but do a piece on biden.Maybe you should explain why biden,tom lantos,joe dioguardia lobbyed so hard for the albanians(cash).Joe biden also said all serbs should be in concentration camps,very human of him.God bless Serbia.