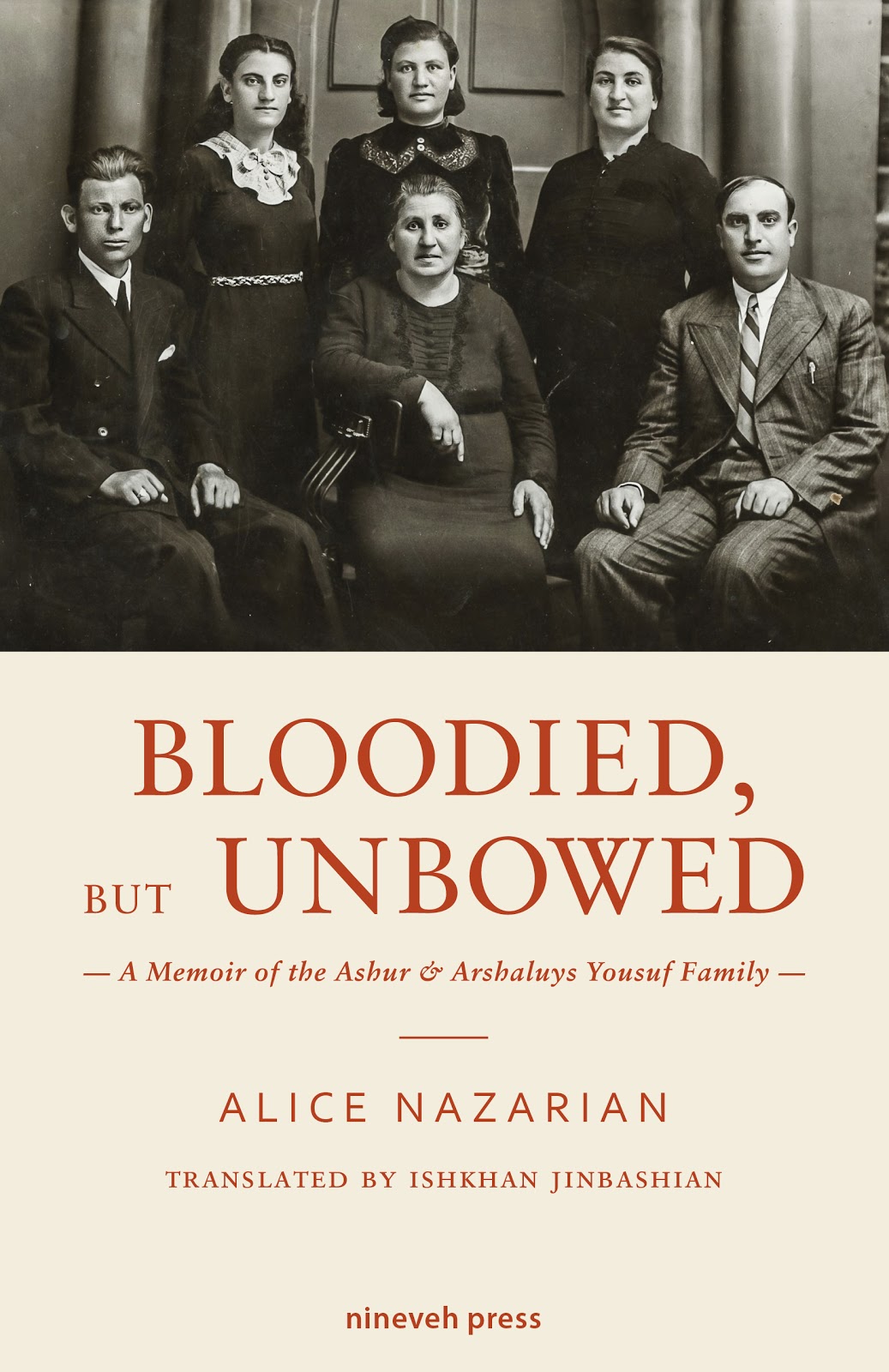

Bloodied, but Unbowed: A Memoir of the Ashur & Arshaluys Yousuf Family by Alice Nazarian

Bloodied, but Unbowed: A Memoir of the Ashur & Arshaluys Yousuf Family by Alice Nazarian

Translated by Ishkhan Jinbashian

Edited by Arda Darakjian Clark

Nineveh Press, Mölndal, Sweden, 2018

425 pages

Ashur Yousuf (1858-1915) is a legend among Assyrian nationalists. He was one of the first Assyrian intellectuals to embrace the idea of a unified Assyrian people that would transcend denominational divisions. As a victim of the Ottoman genocide, he is honored as a martyr. Yousuf was a teacher at Euphrates College in Kharpert and married to an Armenian woman, Arshaluys. In 1965, their daughter Alice Nazarian published a book in Armenian about her parents which has been translated into English and is now published together with some other material by an Assyrian publisher. It is an interesting story well worth reading.

In the first part of the book (pp. 21-220) Nazarian tells the story of her mother. After her husband was killed, Arshaluys Yousuf took care of their six orphaned children in Kharpert. In 1917, she became the director of an American orphanage and after moving to Diyarbakir two years later, she took up the same post at the Armenian Evangelical school there. In 1921, the family moved to Lebanon, where for some years Arshaluys worked in different orphanages. Four years later, she became the principal of the Evangelical school in Homs, and two years later, the family moved to Aleppo, where she continued to work for different schools. During the repatriation, she relocated to Soviet Armenia.

Arshaluys Yousuf was a hardworking, dedicated teacher and caretaker of orphans. The death of her husband was not the only tragedy in her life, but she overcame them all with a strong will and faith in God. In 1957, however, upon receiving the news that her son and grandson had been exiled to Siberia, she died of a heart attack.

Nazarian dedicates the second part of the book (pp. 221-352) to her father. As she was only five when he died, this part is not based on her own memories, but on other sources. Unlike in the first part, the editor has made several editorial comments and additions.

It is good to speak well of one’s parents, but the praise Nazarian heaps on her parents is sometimes panegyric. Her mother is said to have been “angelic.” There is frequent talk of her “tender smile,” and she is described as an “extraordinary talent.” Nazarian claims she was respected and loved by all her students, although she admits that her mother believed “in the effectiveness of the cane.” Ashur Yousef is described by his daughter as having had an “extraordinary intellect.” Assyrians have likewise praised him highly, depicting him as “the star that once shined upon the black firmament of the Assyrian people” and as the “greatest of all Assyrians.”

Ashur Yousef worked as a teacher at both Armenian and Assyrian schools in the Kharpert region. After coming into conflict with arch-conservative Assyrian clergymen, he left the Assyrian school in 1895 and joined the faculty at Euphrates College, where he taught Armenian, religion and psychology. In 1909 he founded the magazine, Murshid Athuriyon (Spiritual Guide of Assyrians), which he hand-wrote in Turkish with Assyrian letters. In it he advocated the cultural, spiritual and political rebirth of the Assyrian people without, however, supporting independence, as he feared it would give the Turks the perfect excuse to perpetrate massacres.

This part of the book also contains poems by Yousuf, originally written in Armenian and Turkish, and three articles. “What is behind the cultural stagnation of the Assyrians?” has legendary status among Assyrians who generally find the analysis still relevant today. With the article, “Some means for the eradication of alcoholism,” Yousuf won third prize in a competition for the best essay on fighting alcoholism.

The book ends with an appendix (pp. 353-425) containing a family tree, pictures, endnotes and bibliography.

Bloodied, but Unbowed is informative and factual about dates and events, thereby managing to clear up a mystery. On the Internet, including Wikipedia, one can find erroneous claims about the death of Ashur Yousuf and even references to a fictitious farewell letter. It turns out that these inaccuracies first appeared in an article in which the author describes a dream he had of returning to his hometown of Kharpert. Ashur Yousuf was not, as the writer claimed in his dream article, imprisoned on April 14, 1915, and hanged the following day, nor did he write a farewell letter. He was arrested on May 1 of that year and deported to an unknown fate on June 22.

There are, however, issues that this book does not clarify. One is the religion of the Yousuf family. Despite constant conflicts with clergymen, Yousuf was a committed Christian. That he was a Protestant is mentioned only once, in passing, in a letter his wife wrote in 1934. Arshaluys herself was the daughter of an Evangelical minister and later worked for institutions run by both the Evangelical and the Apostolic church. So in what church did the family worship, in Kharpert and later in the different places where they lived? Nazarian does not say.

The Yousuf family was both Assyrian and Armenian. Like other Assyrians in Kharpert, Armenian was Ashur’s mother tongue. He also mastered Turkish, spoke English and, according to one source, “toward the end of his life” he learnt Syriac. His wife Arshaluys was from an Armenian background, but in a letter to an Assyrian magazine in 1920, she talked about the Assyrian people as “our nation.” There’s no doubt that she identified with the people so dear to her husband, despite the family being fundamentally Armenian. They spoke Armenian, gave Armenian names to their children, worked in Armenian institutions, and, at the end of her life, Arshaluys and two of her children moved to Armenia, where her oldest son was already living.

Nazarian is silent about how the Assyrian heritage was preserved in the family. Once she writes that her mother “installed and nurtured in her children respect toward and interest in her educator husband’s beloved people, the Assyrians.” Unfortunately, she says no more about this, about how it was “installed” or how the respect and interest was expressed.

It is interesting to note that one of the founding fathers of Assyrian nationalism was in fact as Armenian as he was Assyrian. Several of the early Assyrian magazines in the US were published in Armenian. This was true of the organization called the Assyrian Five Association, which in 1919 published a booklet in honor of Ashur Yousef. The booklet, The Incomparable Assyrian Torchbearer, was published in Armenian. The story of the Yousuf family, therefore, is yet another witness to the close bonds that link the Armenian and the Assyrian people.

congratulations for writing this story so no one can ever forget