BELMONT, Mass.—Somehow, a photo of Robert Aram Kaloosdian standing before Mount Ararat answers a definable cause.

It’s as if he were built into the infrastructure, following a lifetime of public service to the Greater Boston Armenian community and the diaspora at large.

He’s practiced law for more than 50 years and has devoted much of his life to the recognition and study of the Armenian Genocide.

Add the fact he was founding chairman of the Armenian National Institute and a founder of the Armenian National Assembly, and you may not have even scratched the surface. Maybe touched it.

Of particular note in this Centennial year, Kaloosdian participated in defending a school curriculum guide against genocide deniers in federal court. If it wasn’t the genocide, it’s been his connections with Armenian independence, the Apostolic Church of America and many, many ties with the political elite both here and in Washington.

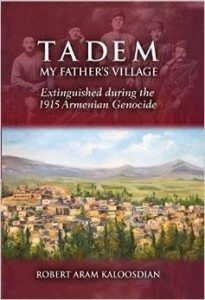

Finally, after all these years, go ahead and add “author” to his resume. His one and only book is a remarkable and proud testament to his father’s village in Ottoman Turkey, called Tadem.

It’s a place that bore the brunt of massacre and hardship during the 1915 assault by the Ottoman gendarmes. The book has been a mission in waiting, ever since Kaloosdian’s younger days. He wanted to share the truth with his world, but more important, to give closure to that moment in his dad’s history and the 270 others who were butchered inside this locality.

“It is difficult to understand the extent of the horror that befell such a small farming village by not only its government but also by its neighbors and friends who unquestionably obeyed their government and religious leaders,” Kaloosdian points out.

In all, 250 Armenian homes were burned, leaving another 100 wounded. His two trips to Tadem have remained etched in his mind. Pathetic yet poignant.

A grandfather of five, Kaloosdian documented the collective memory of anyone and everyone he could reach who lived in this specific region.

“The example that Tadem presents teaches us what a destructive weapon religious hatred and prejudice can be,” he says. “The destruction of a people does not rely on orders coming from a central authority.”

In his research, Kaloosdian discovers there were people who jumped at the opportunity to terrorize and murder the Armenians of Tadem. He found the origin of the “Armenian problem” not to be the sultan alone—but, rather, the locals who were given positive cover by the Ottoman authorities to subjugate the Armenian population.

The author tells the individual stories of these Tadem villagers and their extraordinary efforts to survive the genocide that exterminated the majority of this community.

Through descriptions of his father’s arduous journey from his ancestral homeland across Siberia to Japan, then to Seattle and America’s East Coast, Kaloosdian describes in detail individual choices made by his father as well as other Armenians, Turks, and Kurds.

In doing so, Kaloosdian effectively clarifies what genocide actually details. It’s a book anyone who knows or doesn’t know Armenia’s history would get to appreciate.

The jacket pulls the reader inside, showing the village of Tadem in remarkable clarity, done in color. A mere look would entice any reader to consider a possible visit.

Over the next 300 pages, you get an overview of life in this town, its people and its history. It is not Erzurum or Van, Bitlis or Dikranagert. It is Tadem, and you may not have heard about this place had it not been for Kaloosdian’s dad Boghos. He dedicated this work to his beloved “Hairig.”

Covered inside the contents is a rich repository of information that puts the reader right into the thrust of history, beginning with a Tadem childhood to its Educational Society, the deportation of women in this village, and the massacre of remnants.

It continues with Boghos’s journey to America, a retreat through chaos and revolution, and hits upon life in America—the early days, the foundry where he worked, the club he frequented and the people he befriended.

You’re about to revisit that devastating hurricane in 1938 that uprooted Watertown where he lived, and finally, a postscript of the destinies of Tadem survivors.

It’s a crossover between East and West—immigrant to citizen. Maps, testaments, and interviews make this a poignant read. It’s a work that probably wrote itself with Aram’s initiative.

One striking section of the book is about the women who survived the July 1915 deportation. I was particularly enamored by the immigration struggle; they were like so many others who came to America and cultivated a dream.

Out of it came a son named Robert Aram who was encouraged to get an education and found his way to law school and ultimately success. We owe our survivors a debt of gratitude for their sacrifice, foresight, and resilience. Education was their mantra.

We owe the Boghoses of the world our survival, our success. This book is about Tadem. In fact, it’s about any village facing a cloud of despair and seeing the sun shine through on a tragic history that has since turned notable.

We applaud such an inspiring book.

Be the first to comment