This was the title of Dr. Khatchig Mouradian’s talk, presented at NAASR on Thursday, November 14, 2024. In it, he explored the houshamadean, memorial book, as a literary genre, art and artifact. His research was in-formed and re-formed by nearly two dozen trips to the sites that these books memorialize: the “lost” villages of Western Armenia. In 2017, I accompanied Mouradian on one of these pilgrimages.

But this journey begins backwards.

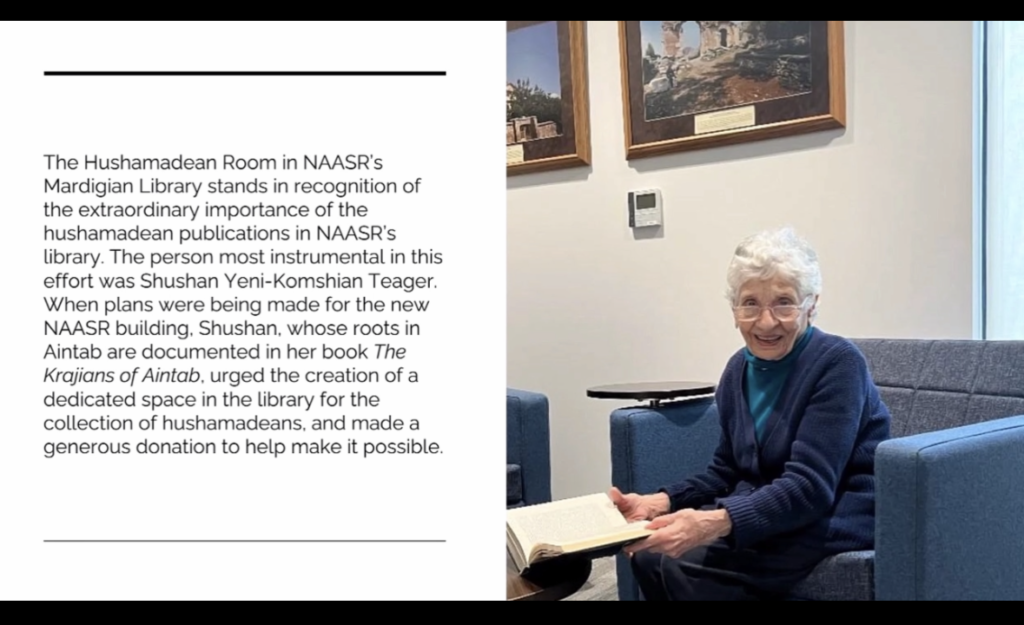

Mouradian’s talk is lifted from the title of a paper, in an upcoming special issue of Wasafiri Magazine dedicated to Armenia. NAASR Director of Academic Affairs Marc Mamigonian found it the perfect homage to the late Shushan Yeni-Komshian Teager, who played a vital role in NAASR’s collection of housahamadeans. Mouradian’s talk was dedicated to Teager’s memory — a memory book as memorial.

In his introduction, Mamigonian described Teager as “an unofficial ambassador to assist researchers.” I recalled our one interaction, at the old NAASR building years ago, buried in a collection of poetry. Teager kept me company, rattling off story after story, a consummate raconteur. Her son, Daniel “Dan” Teager, inherited her ebullience. After adapting Armenian sacred music to the trumpet, he performed his mother’s hokehankist (requiem) service with a brass choir. “She would’ve loved it,” he smiled.

This, perhaps, encapsulates the re-creation that Mouradian described. The melding and blending of the old with the new. Houshamadeans were the survivors’ way of preserving their “lost” villages, until they would be found again — perhaps only on the page, but a memory nonetheless, for future eyes to inherit.

Houshamadean itself was a word born of necessity. A combination of housh, “memory,” and madean, a manuscript that denotes distant or lost times, as defined by the team at Houshamadyan, a website that recreates Ottoman Armenian village life. Though no films or books have been created based on the stories contained within the memory books, the website resembles a computer game — a virtual holding ground for the worlds salvaged from destruction and (re)created in the books.

Housh is memory, but oush means late. There is an element of memory that feels like catch-up — like being hit unconscious and waking up after your entire village has been decimated. We run back (in)to a clock that wishes to shed old skin.

Then, of course, there’s the Armenian expression, oush lini, noush lini. “Let it be late, but let it be good.” Oush lini, housh chlini. “Let it be late; let it not be a memory.” Except in a book.

“This whole genre of literature is a product of something that was lost,” Mouradian explained. He described similar genres that came out of the Holocaust and the Nakba, among other tragedies. These world-building and sanctifying endeavors have not been given the importance and careful examination they deserve.

To this, Mouradian said, “There is a great world history of memory books that waits to be written. This is an opportunity to explore what home means to human beings and [its] transformative power.”

Similarly, when asked during the talk why this work was ignored for so long, Mouradian explained that much of genocide scholarship has focused on the legal aspects, “to prove” that the crime happened. Less energy has been spent on re-aligning the scattered seeds — a losing strategy everywhere, we’ve learned. Oush lini, noush lini. Like the clock turning inward, hindsight is foresight.

But the nature of memory is fickle, lending itself to many interpretations and re-constructions. Mouradian shared that some villages have multiple memory books, because somebody did not like the way that their village was represented, so they commissioned a new one — in their image. There are as many truths as people, or as the old adage goes, “two Armenians, three opinions.”

When describing any book, one must examine the spaces between the lines. And for the plethora of voices in the memory books, there remains a huge gap.

Mouradian mentioned the lack of female accounts, noting the example of two midwife sisters in Aintab, who together delivered over 8,000 Armenian, Turkish and Kurdish children until the Genocide, then more in their exiled homes in Syria. “Their [male] relatives are everywhere in the record, but they are totally left out,” he lamented.

The other day, I mentioned to my friends that a relative had prepared our family tree, dating back to my great-great-great grandfather in Sasun. The branches, hand-drawn, build upon each other. But the women become leaves. Their line does not continue. Mine stops at my mother.

The complicated legacy of this work is that women don’t get a name to carry into the tree, into the book. Memory becomes half-complete, kis-a-housh. In 2002, Teager published an article titled, “Armenian women lost to history” — lost, like a home-land — not even a footnote on the maps.

Here, Mouradian quoted another leaf, Joan Didion: “A place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically that he remakes it in his image.”

Re-made in his image. It’s hard to not read the Biblical implications. Indeed, some houshamadeans represented an idyllic Eden, the beauty before the rupture. Others held truer to a more realistic, perhaps even gritty, depiction of Ottoman Armenian life. In one example, one re-member-er describes the smell of his village outhouse. But even in the foulest of memories, there is no doubt to whom the place belongs — if even only in housh.

Mouradian discussed how compatriotic unions banded together in the diaspora to commission memory books on their villages, often hiring a professional editor or historian to oversee the work. “This is the biography of a city, and let me do everything possible to make it come to life,” Mouradian explained. Sometimes, they weren’t professionals, and they knew that they were collecting and recording information for the future historian to have a housh to turn to.

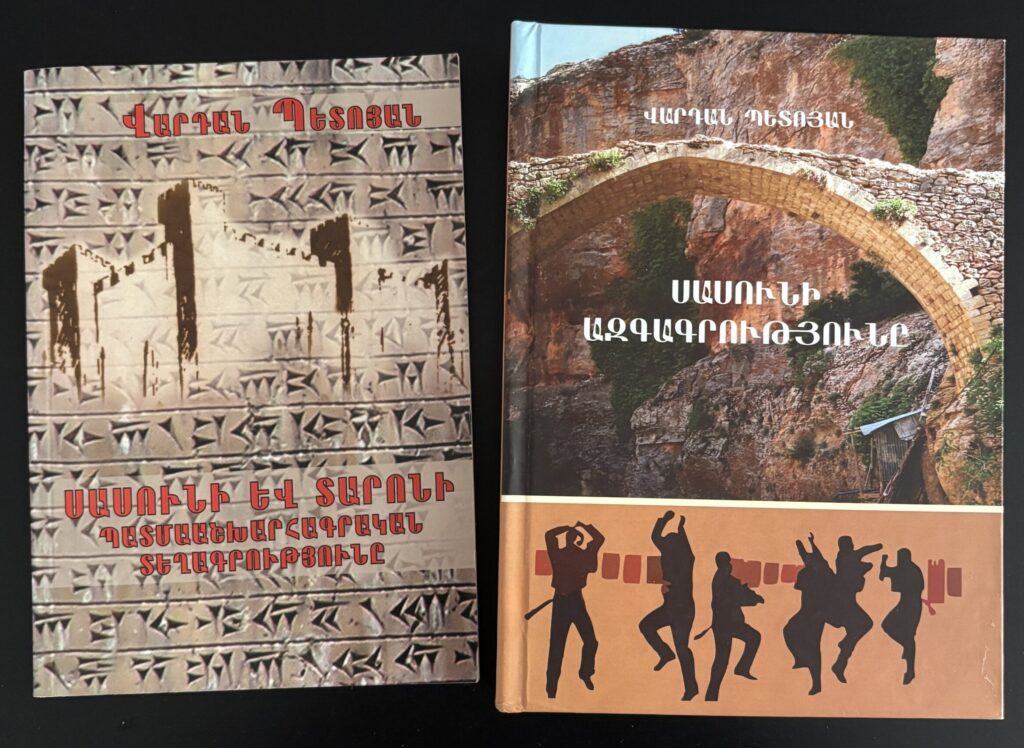

He mentioned how villages were reconstructed in Soviet Armenia. Among them, Nerkin Sasnashen, is the village that my mother’s grandparents, refugees from Sasun, co-founded. In an earlier talk given at Columbia University, I asked Mouradian about the memory books that were published in Soviet Armenia.

While memory books flourished in the U.S., Lebanon and France from the 1920s until the start of World War II, in Soviet Armenia there was no room for memory under Stalin’s fist. But our village is a type of memory book-come-to-life. Even today, one can trek up and down our mountains, hear our dialect and get a little disoriented: is this the real Sasun or a memory re-enacted?

Mouradian answered my question by saying that the memory books came later in Soviet Armenia. “Most were produced from the 1970s and 80s and were highly censored,” he explained. In one of my memory books from that period, the Russians are portrayed as super-heroes, the saviors of my people. They were so grateful that they decided to settle in Russian Armenia.

The world war brought the production of the memory books to a grinding halt. But in the 1950s and 60s, publication ramped back up again, partially driven by the 50th anniversary of the Genocide. Mouradian described how the memory book on Sepastia (Sivas) took 32 years to reach completion. In the introduction, the author writes that “he must have survived the genocide for this purpose.” Mouradian added, “It must have been his way of coping with survivors’ guilt.”

Guilt is a loaded word often confused with shame, “amot.” I began by noting that this journey moved in reverse.

In Western Armenia, I saw the after — what was not contained in the books — before even reading the stories. At the time, I had just discovered that my great-grandmother was from Garin. Walking the streets of “Erzurum,” I did not recognize anything — no bodily familiarity that could have resembled a housh of any kind.

Some months ago, Mouradian sent me a pdf of a memory book on Garin. I’ve been making my way through its 300+ pages — a daunting endeavor. But even more daunting is the imposter syndrome. Re-membering Didion’s words, I still don’t feel like Garin is mine to claim, even in memory.

After the author’s introductory note, my eyes jumped back to a familiar spot, like that table at NAASR and the leaf beside me, narrating the wind. Page 70, on Garin poetry.

The first poem was titled “Menis,” from Ancient Greek, meaning “wrath of the gods.”

Neither home nor garden do I have,

Only problems do I have —

Just like the birds of the sky,

No place to rest do I have.

Oush lini, noush lini. Page by page, line by line, I felt a thawing.

Dr. Khatchig Mouradian is the Armenian and Georgian Area Specialist at the Library of Congress and a lecturer in Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies at Columbia University. You may view a recording of the talk described in this article on NAASR’s YouTube channel.

Be the first to comment