In the basement of the Hairenik Association in Watertown, Massachusetts, more than a century of history lies safely tucked away. Here, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) Bureau keeps the party’s archives, with material spanning from its founding in 1890 until 1992. George Aghjayan, who has been director of the archives since 2017, guided me through a tour of the ARF Archives, some new acquisitions and ongoing projects.

History permeates every level of the Hairenik building. Prior to the descent to the basement, a part of the archives is stored on the first floor, which houses the Armenian Weekly office. In a small storage room, four-page spreads, entirely in Armenian, are bound into massive tomes by year, dating as early as 1899. Their digitized versions are available in the Hairenik Digital Archives collection. As the books grow older, the pages grow yellower and more delicate, the covers loose and faded, until they are too risky to flip through for fear of damage. Those nine decades of storytelling rest next to the computers housing the stories of today. The 90th anniversary of the Armenian Weekly is approaching next year, along with the 125th anniversary of the Hairenik newspaper, and decades from now, this week’s paper may sit on those big shelves in a tome, waiting to be rediscovered.

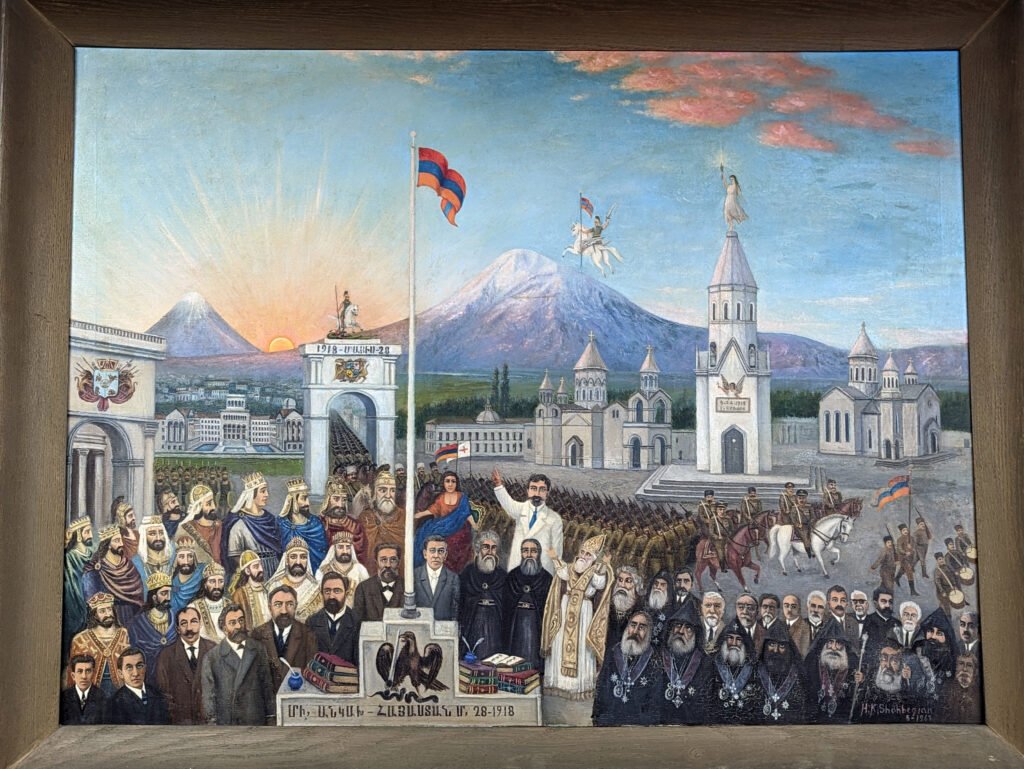

The first floor also houses a painting revering Armenian history and culture: Spirit of Armenia, painted by Haroutiun (Harry) Shahbegian. Shahbegian was born in 1889 in Kharpert and fled to America at age 17 after the Turks issued papers to have him hanged. The family he left behind did not survive the Genocide. He volunteered as a Freedom Fighter during the Genocide and was well regarded by the generals for his skill. He married and had three children, to whom he passed down his Armenian values.

Spirit of Armenia represents Shahbegian’s love of Armenian history and culture, as well as his belief in Armenian independence. The piece was completed on May 28, 1963, on the 45th anniversary of Armenian independence, and honors those who aided the Armenian cause. Depicted are Armenian Kings, President Woodrow Wilson and the founders of the ARF. Shahbegian also paints Soghomon Tehlirian, a personal friend of Shahbegian’s whose impacts on Armenian history have recently been expanded upon in the ARF Archives. Though self-taught, Shahbegian’s work reflects the memories of his homeland and his dreams of Armenia’s independence, and it watches over the staff of the Armenian Weekly as they write for and about the Armenian people.

Down in the basement, every piece of paper from 1890 to 1926 has been cataloged, microfilmed and organized into 27 chronological volumes of catalogs. The documents from 1926 to 1940 are organized by theme or subject, and materials after 1940 are split into 225 cataloged boxes. “The archives also include the archives of the First Republic of Armenia, including the 1918 Declaration of Independence, and continuing past the fall of the Republic to the Diplomatic Mission in France and the Paris Peace Conference,” Aghjayan shared while he and his colleague Mary Choloyan were busy cataloging documents in the archive.

The archive’s current project reflects the time after the Republic fell, when Armenia’s government was acting in exile, and Armenians had no citizenship in any country, similar to other post-WWI refugees. The League of Nations, an international organization resolving post-war disputes, created the Nansen passport in 1922 to aid refugees, but Armenians were not added to the program until 1924 and could not travel. In response, they applied to the Diplomatic Mission in France. Aghjayan’s grandmother “came to the United States in 1928 on a passport issued by the Republic of Armenia in 1928. There had been no Republic of Armenia for eight years at that point, but the United States Government still recognized and honored that passport, and she was able to enter the U.S. on it.”

The archives hold 20,000 of these passport applications. Each one features “a photograph of the person, their name, where and when they were born, the father’s name and the mother’s maiden name,” Aghjayan said. Also collected are letters attached to the applications and some actual passports, stamped and signed in swooping cursive on large stationary sheets, edges perforated as they were torn out of a register book. These applications are a significant acquisition. They may be the only pages containing so much genealogical information about these Armenian communities. Aghjayan’s team hopes to have the passport applications entirely cataloged and available online by the end of the year. The first 2,000 are already accessible on the ARF Archives website, arfarchives.org.

Alongside the passports, Aghjayan’s team is completing high-resolution scans of thousands of historical photographs, housed in over 30 boxes. They span a wide range of themes and years, and they are being cataloged and uploaded to the ARF Archives website.

With the archive’s current work explained, it was time to venture into the vault for a peek at the passports and alternate acquisitions. Beyond the basement’s working room lies a large vault. Stepping up into the sealed, temperature-controlled gray room, rows of ceiling-high shelves boast small charcoal boxes. Walking across the room is like a chronological walk through history, each row of shelves preserving a different block of years. Here lie some of the ARF’s great treasures.

The vault stores letters to the editors of Hairenik’s monthly magazine, which ran from 1922 to 1970, including content that was never published; private papers from influential Armenian figures; and copies of a book celebrating the 100th anniversary of the ARF, filled with photographs and history.

Aghjayan stopped near the entrance to the vault to point out an unassuming box. Inside lies a collection donated by the grandson of Manoug Hampartsumian, the editor of the Hairenik newspaper from 1914-1916, with documents detailing his life and work. Several of the correspondences are on Hairenik letterhead from the time. The collection also contains letters from his time at Anatolia College in Merzifon, including correspondences to the woman he would later marry while she was at Euphrates College. An active member of the party, Hampartsumian wrote several political letters in the 1920s and 1930s. He was later appointed as a delegate to the World Congress in the 1950s, from which the archive retains his postcards detailing his journey through France, Switzerland, and Cairo, Egypt. The collection is a portrait of his life as conveyed through postage.

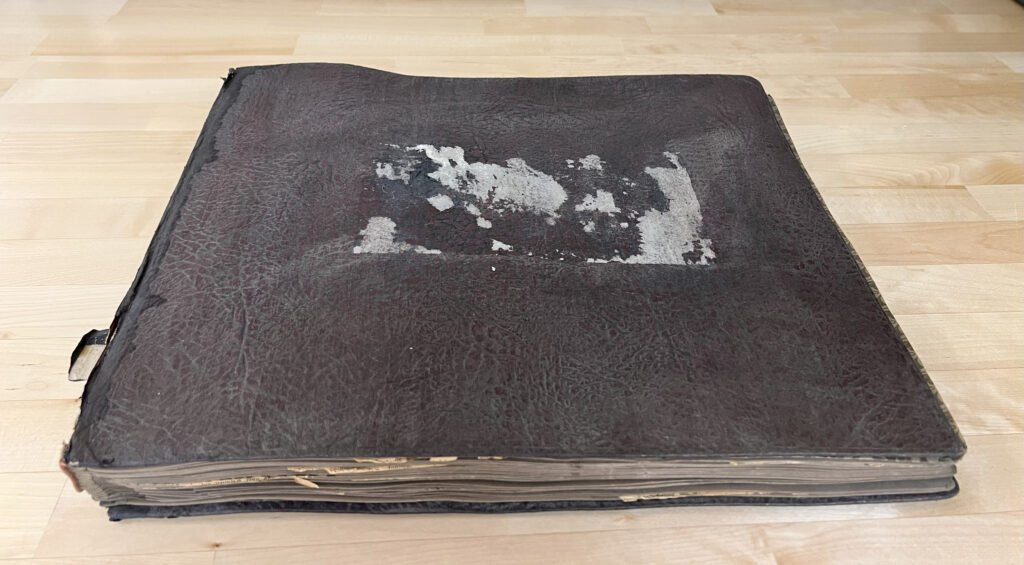

Additionally, Aghjayan recently purchased a scrapbook compiled by someone in Germany during the trial of Soghomon Tehlirian. Tehlirian was found not guilty and freed after assassinating Talaat Pasha, the former Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire, in Berlin in 1921. The scrapbook contains news clippings detailing the assassination and trial. It is believed that Shahbegian, the artist behind Spirit of Armenia, gave Tehlirian the Luger pistol used to assassinate Talaat. Tehlirian’s story and his friend Shahbegian’s painting are now housed under the same roof.

Last, Aghjayan presented a metal box donated by the Mike Mugerditch Paloulian family of Worcester. The tarnished box is small enough to fit in the palm of a hand, with a keyhole in the center. The rest of the center plate is engraved with the ARF name and logo. This box was used for collecting money to buy bullets. There is a hole to insert bills on the left side and a coin slot on the right. Among boxes of paper records, this box is a unique artifact addition to an archive dedicated to preserving Armenian history.

The ARF Archives are ever-expanding. The next addition is a recent acquisition of Hunchak material, expected to arrive soon. After that, the Archives will continue to collect and preserve Armenian culture.

Consider supporting the archives and its projects preserving history through a donation. Please reach out if you have any ARF documents or photographs that you would like to share.

Be the first to comment