I am Vahagn Khachatrian, a young journalist from Artsakh. I am writing this while in blockade. Can you imagine it? Artsakh, this free and independent republic that’s home to 120,000 people, is like a prison today. A group of so-called ecologists decided that they can wake up one day and close the only road to mother Armenia, trapping thousands of people.

These are “ecologists” in whose hands the symbol of peace — pigeons — suffocate. These are “ecologists” who cut off the supply of gas, food and medicines to Artsakh under such cold conditions; who don’t allow the transfer of critically ill patients to Armenia; who deprive thousands of children of the right to education; who don’t allow children to return home to their families and the relatives of the deceased to come to see them for the last time.

Since the only thing I can do is wander in this prison, I’ve decided to visit my birthplace Ashan to see how people there are managing to survive this humanitarian disaster.

My first interlocutor is Raisa Tadig. I spent much of my childhood at her home. Raisa is 75 years old. In her life, she has witnessed and overcome many challenges. She took part in the Artsakh Liberation Movement and the emergency session on February 20, 1988.

According to her, at that time it was very difficult to get to Stepanakert as the Azerbaijanis used to throw stones at the Armenians’ cars.

That momentous day, however, changed the course of our history.

Now, she says that we are toys in the eyes of the Azeri and regrets not driving them up to the Kur River.

“How are we bothering them today? We aren’t eating their food. We aren’t drinking their water. How are we disturbing them? We aren’t affecting their livelihood. So, what is this situation? Our people live on a very small land, because they occupied 75 percent of our territory and won’t even let us live on the 25 percent that’s left. There are children and elderly who live here. As if that’s not enough, they cut off gas and are forcing us to use a wood stove,” says Raisa Tadig.

She calls on the world to make those people open the road. A survivor of three wars in her lifetime, Raisa’s only wish is peace.

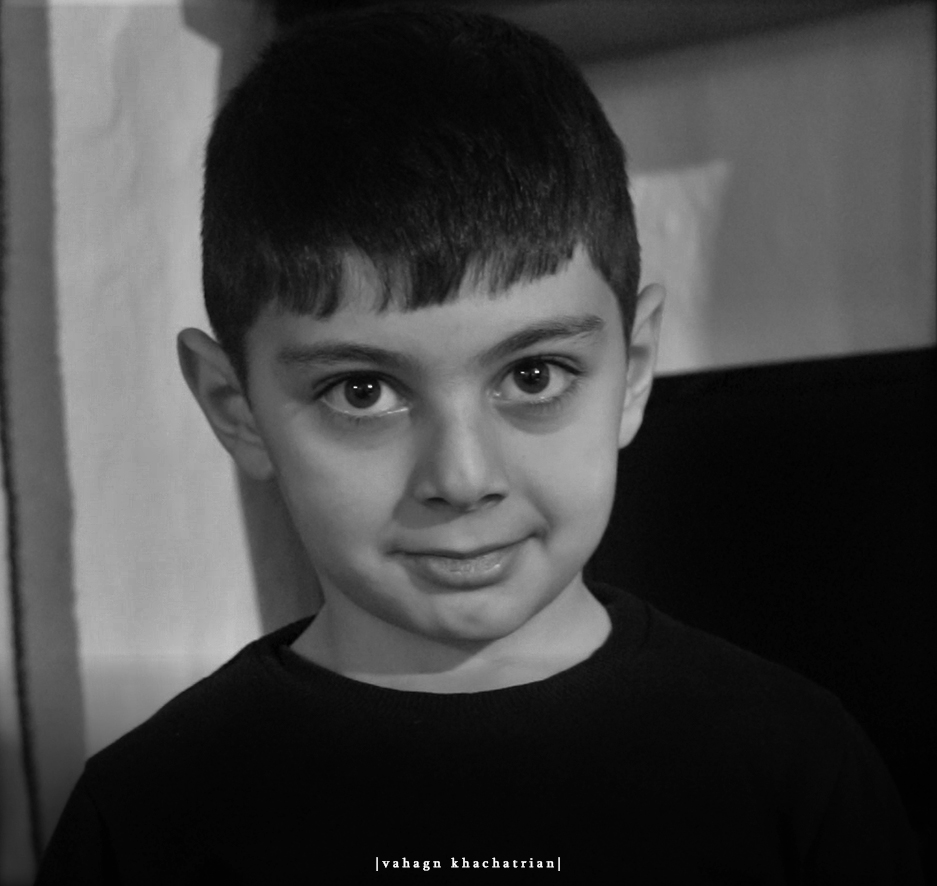

Martin is six-years-old. He is a student at Anita Hovsepyan Secondary School in Ashan and likes to read rhymes. His favorite rhyme is about peace, homeland and people. He knows that our world is a home for everyone, and all the people in the world are a big family. But, Martin can’t understand why the Armenians aren’t allowed to live in their homes peacefully.

“As the Azerbaijanis cut off the gas, I can’t go to school,” says Martin, adding that he loves his classmates and wants to go to school every day and study well so that the Azerbaijanis don’t occupy his village Ashan.

One of the oldest shops of the village is Tigin Gohar’s shop. It has been supplying villagers for years. Villagers could find anything they wanted in this shop. The shop is empty now. Gohar Kocharian doesn’t sell New Year’s presents like she used to this time of year.

She describes her shop with one word: emptiness.

According to her, there is no problem with the supply of bread yet, but cigarettes and other goods imported from Armenia are running low. If the blockade continues, they will obviously run out of everything.

“We are rationing goods in order for everyone to receive a share, and we will survive with the little that we have. It’s important for the road to open, for people to come to their senses,” says Kocharian. “It’s wrong to allow such actions to take place in the 21st century. We have to be able to defeat evil, to think with our minds and not with our stomachs. But we can endure this, so long as there is no war. As our forefathers would say, it’s better to eat stale bread but have peace.”

Arman Sevumian, who also had many dreams and goals, lost his home in Shushi in 2020. He got married and moved to Ashan to live here with his family. He says that even after the war they still wanted to live in Artsakh, but they were faced with a very sad situation.

“The world doesn’t respect human rights. It ignores the people,” says Sevumian. “This blockade isn’t scary for me, but it is shameful. The road must open because many children are away from their families, and they must reunite.”

Sevumian calls on the world to recognize Artsakh because he and his compatriots refuse to leave the region.

“If I have to die, then I’ll die here as an Artsakhtsi,” says Sevumian.

Ashan is home to a small clinic. One of the nurses, Gohar Avagyan, is concerned about the blockade and its tragic consequences. She reports that there is enough medicine for their patients for now, but the supplies are exhaustible.

She also mentioned the problem of transporting patients to hospitals due to the shortage of petrol.

“Our building’s heat is electric, but the school and kindergarten have gas heating. If they shut off the gas again, it will cause serious problems for education. In this season, diseases spread immediately, and the medicine is running low. We hope that this situation won’t last long and the road will soon open,” says Avagyan.

She recalled that they have been in this type of a difficult situation before, especially during the 44-day war, but they never lost hope.

They still have hope. They would never imagine leaving Artsakh no matter how long the enemies keep them under siege.

Satenik Grigoryan is one of the lucky ones who was able to fulfill her biggest dream. She was waiting for a baby for eight years until the miraculous birth of her daughter Astghik. But today, Astghik, who was born just after the war, is at risk of starvation because baby food, necessary medicine, creams and diapers are all imported from Armenia.

Grigoryan never considered leaving Artsakh even after the war because all her dreams are connected to Artsakh. “I want my children to be raised in Artsakh. We have earned the right to live in Artsakh,” says Grigoryan.

She says that her family is often stressed because of ongoing problems which are passed on to their children.

Dear reader, this is what life is like in blockaded Artsakh. The cries of our people are inaudible for most countries.

Despite all these difficulties, life continues. Since the day of the road closure, 26 babies have been born in Artsakh.

In the 1990s, Artsakh was blockaded as well, but under worse accommodations. There was no gas, no electricity and no food. The towns and villages were being bombarded all day long, but the people continued to live, study and grow their families.

The people of Artsakh and authorities have made their choice not to make any concessions to the enemy. We are united. The right to live on this land is inalienable. We will live because we owe it to all those boys who sacrificed their lives for the freedom and independence of this country.

Recognize Artsakh’s right to self-determination.

Be the first to comment