Sitting in his reclining chair with a checkered sleeveless sweater and a white mustache that practically spells out “quintessential Armenian dede,” Amo Hovan calmly greets me, “Ahlein Kegham.” Television remotes are studiously stationed on the adjacent coffee table. To his left, there’s a wide spanning brown cupboard with framed pictures of family and a collection of VCR and DVD recordings, ranging from the 1953 biblical epic The Robe to Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo: First Blood.

“Inchbes filmuh ge hedtseneyir?”

Hovhannes Bedrossian, eyes closed, instinctively motioned the technique used on the Gaumont-Kalee GK20 film projector: “filmuh veri aniven, vari anivuh.”

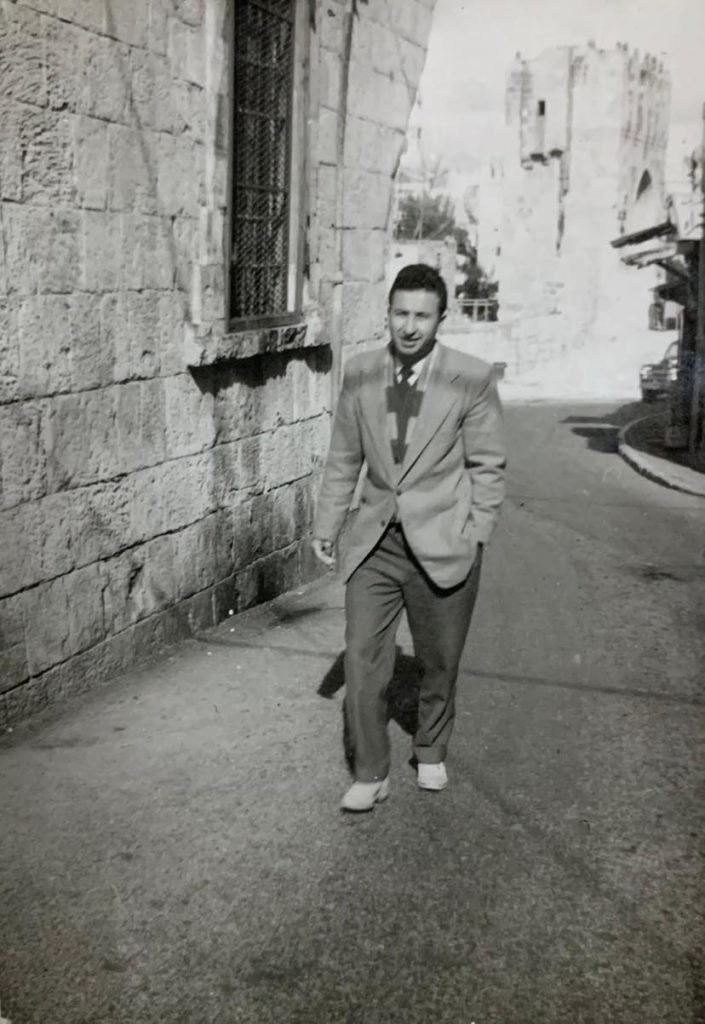

Born in 1935 in Jerusalem to Nuritsa Bedrossian (neé Juvelekian) and Bedross Bedrossian, Amo Hovan always had a passion for cinema. “Shad ge sireyi. Yev or muh goozeyi operator elall, yev yegha, hachoghetsa,” he said.

A first-generation Armenian, post-genocide, his father from Ourfa, his mother from Aintab, having found each other at the entrance of the welcoming Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem, along with thousands upon thousands of other refugees. Their lives were saved, but far from easy: a household, basically a mere room, contained at times 10 to 15 refugees, from different families, taking turns with sleeping on the available mattresses, as well as sharing communal lavatories within the confines of the St. James Armenian Convent located in the Armenian Quarter atop Mount Zion—a large gate insulated within its walls our heritage and future, our boys and girls, soaked in pain and hope, struggling to emancipate the latter from the former; a gate that to this day adheres to a curfew which prompts it shut come 8 o’clock and reopens at 5 in the morning [the curfew has since moved to midnight].

In 1948, the Arab-Israeli conflict erupted following the end of the British Mandate of Palestine, which led to the establishment of Israel and the division of Jerusalem into East and West under Israeli and Jordanian rule, respectively, adding more pressure to the already strenuous lives of the traumatized survivors.

In 1953, funded and established by the investment company Massayef, Cinema Hamra, or The Red Cinema (not to be confused with Al Hambra Cinema in Jaffa, or with any Soviet connotations), opened its doors to the first mixed movie theater in East Jerusalem, with predominantly American and English movies on display, provided by the Hashemite Jordanian Kingdom. Amo Hovan had his sight set. An institution for much-needed merriment had finally arrived. “Amen dessag martig ge kedneyir,” he said. “Hayeruh shad gertayin?” I asked.

I hoped, with a pinch of Armenian pride, for a resounding affirmation, to even be mocked for asking such a question. “Voch,” he firmly said. The curfew placed by the Armenian Convent made it impossible for most to enjoy after-work screenings, so only Sundays were possible, and to my pleasant surprise, the historic St. James Armenian Printing House was charged with printing Armenian flyers for Armenian spectators on that day of rest, but it was hardly a restful environment. With its 319 seats complete with balcony boxes, The Red Cinema was a veritable hub for controlled chaos; from the billowing cigarette smoke that clouded shirts and dresses alike, with rummaging busboys, leather-straps slapped on the back of their necks, macheteing their way through the near-orchestral undulations of popcorn, seeds and whistles in perfect staccato nic harmony. The drunk having bought an entire balcony, to drink, self-deludedly, from prying eyes; the escapist seeking a break from family; the delinquents hiding from the Jordanian National Guard, to avoid recruitment.

“Kezi chi darin?” interjected Tantig Vartoug, Hovannes’ wife.

“Indzi yete daneyin, operator cher menar!”

“Pari pari ge nesdeyir?” I asked.

“Che!” replied Tantig Vartoug and Amo Hovan in unison, the latter with a nostalgic twinkle in his eye. Stereophonic sound didn’t exist at the time, so any adjustments had to be made manually. He would at times wait and wait for silence to take hold of the theater, for the perfect moment, with tension gripping the audience, before abruptly raising the volume! “Deghernen ge tsadgeyin!” he added. Tit for tat.

“Meguh gar vor mishd gookar?”

There was Noubar Arsenian, son of Hagop Arsenian, the famous owner of the Grand Pharmacy of Jerusalem, whose Gomidasian journey from his native village of Ovajik through Aleppo all the way to the Holy Land, was marked by trials that would stifle the soul of any man [check out the book Surviving Massacre: Hagop Arsenian’s journey to Jerusalem 1915-16, written by his granddaughter Arda Arsenian Ekmekji]. According to Amo Hovan, Noubar was an impressively pleasant person and always present whenever there was a screening on Sunday. As a distributor of Old Spice in the region, he would sometimes give samples to young film enthusiasts and ticket holders. A room full of ungodly fumes and stenches, but, here, have an Old Spice. Kusturica is clearly smiling somewhere, I’m sure.

“Inchbes eskesar kordzi?”

Amo Hovan started working at the cinema in 1959 as the cashier. He eventually moved to ticket control before becoming a full-fledged operator in 1960.

“Ov sorvetsouts kezi?”

There was a man by the name of Mohammad from Jaffa who was the operator. A young Hovhannes used to watch him diligently. “Tideh, sorvir.”

“Oorish Hay muh kider operate enel?”

Haroutioun Arakelian operated a cinema in Nablus, some 70 kilometers away from Jerusalem.

“Amen inch ge tskeyin? Censor cheyin ener?”

Amo Hovan smiled: “Gark muh paner ge tskeyin, payts yeteh chapeh antsner, ge haneyin, yev hedo ge ghergeyin tebi Yerousaghem.”

“Kani garjer meg ticketeh?”

Twenty ghouroush for the balcony box, which contained four seats (pricing per seat); 15, 10, eight, and six for the rest of the nine remaining rows [A B C D E F G H I]; 10.5 ghouroush for students. “20 ghourousheh kots mkhrakouyn, 10-eh gabooyd, teghineh oot.” He even remembered the color of the tickets.

“Hech tsri ge medtseneyir martots, martots vor bedk ooneyin?” asked Tantig Vartoug.

“Yeteh jash pereyin!” chuckled Amo Hovan. His wife would prepare him a meal which friends of his would clamor to take in order to get a free entrance!

“Inch jash gar cineman?”

“Amen inch gar, chocolatner, good, sandwichner, dalakh,” he replied casually.

“Dalakh? Cineman dalakh ge dzakheyik?” I asked, barely containing myself.

The caterer in charge of the buffet would prepare dalakh sandwiches once a week and serve them to moviegoers! In a twist of fate, poetically, today, Amo Hovan ranks as probably the best dalakh maker in Jerusalem.

“Film muh ga vor aztets shad amenoon vera?” I asked, hoping, again, to coerce him for a glimpse of Armenianism.

“Sangam by Raj Kapoor,” he answered immediately, referring to the 1964 Bollywood romantic movie.

“Inchbes ge tarnayir doon yeteh vankin toorin curfewn antsneyir?”

He would climb the length of the 10-meter wall adjacent to the entrance of the Armenian Convent and cheekily wave at the angry doorman for having disrespected the rules, albeit for work, nothing else.

Amo Hovan stopped talking, took a pause and continued: “Meg film muh gar, Aryoonabard, Sarky Mouradianin. Mer an jamanagin Tarkmanuh [Chief Dragoman, aka the person responsible for day-to-day affairs within the Patriarchate, as well as serving as an interpreter for visiting dignitaries], Hayrig Srpazan, anchap vor houzvetsav filmen, hraman devav vor vankin tooreh pats mena ayn orere vor an filmuh guh khagha.”

A Debt of Blood starring Sarky Mouradian is based on the book by prominent ARF revolutionary Avetis Aharonian. It told the tale of Bardo, a young farmer who unwittingly betrayed a group of young fedayis who sought nourishment only to be ambushed due to the protagonist’s cowardice. His father ashamed and his family cursed, he eventually manages to redeem himself by taking the life of the Turk who had broken him.

Eureka!

“Kani dari ashkhadetsar iper operator?” I asked.

“1960 minchev 1965,” he said with pride, and even further pride when announcing that the reason for this decision was because of the birth of his daughter. One day on his way back from work, he climbed that very same wall, but only a meter high, slipped and fell on his tailbone. The following day, he handed in his resignation.

“Inchoo chi medadzetsir Ameriga yertal sharunagel?”

“Jagadakir.”

Thank you Kegham and Hovhaness for bringing old memories of my childhood, The Sunday afternoon trip to the movies was our greatest joy. Often a group of Eight or Ten of us will gather at the entrance of the Convent and go as a group. Hovan or other Armenian employees would let us in first to avoid the shoving and pushing at the entrance door of the theater. We sometimes ventured to attend the late afternoon shows, and climb the different water pipes to get back into the convent.