In the spring of 1915, Nigoghos Mazadoorian and his father Garabed came across an early ripening mulberry tree while walking through their orchards in Ichmeh, a village in the Ottoman Armenian province Kharpert. As per the traditional way of collecting mulberries, Nigoghos climbed the tree and shook the branches, and the father and son gathered the fruit that fell to the ground.

“We have tasted the first mulberries of the season. We shall not die this year,” Garabed prophesied.

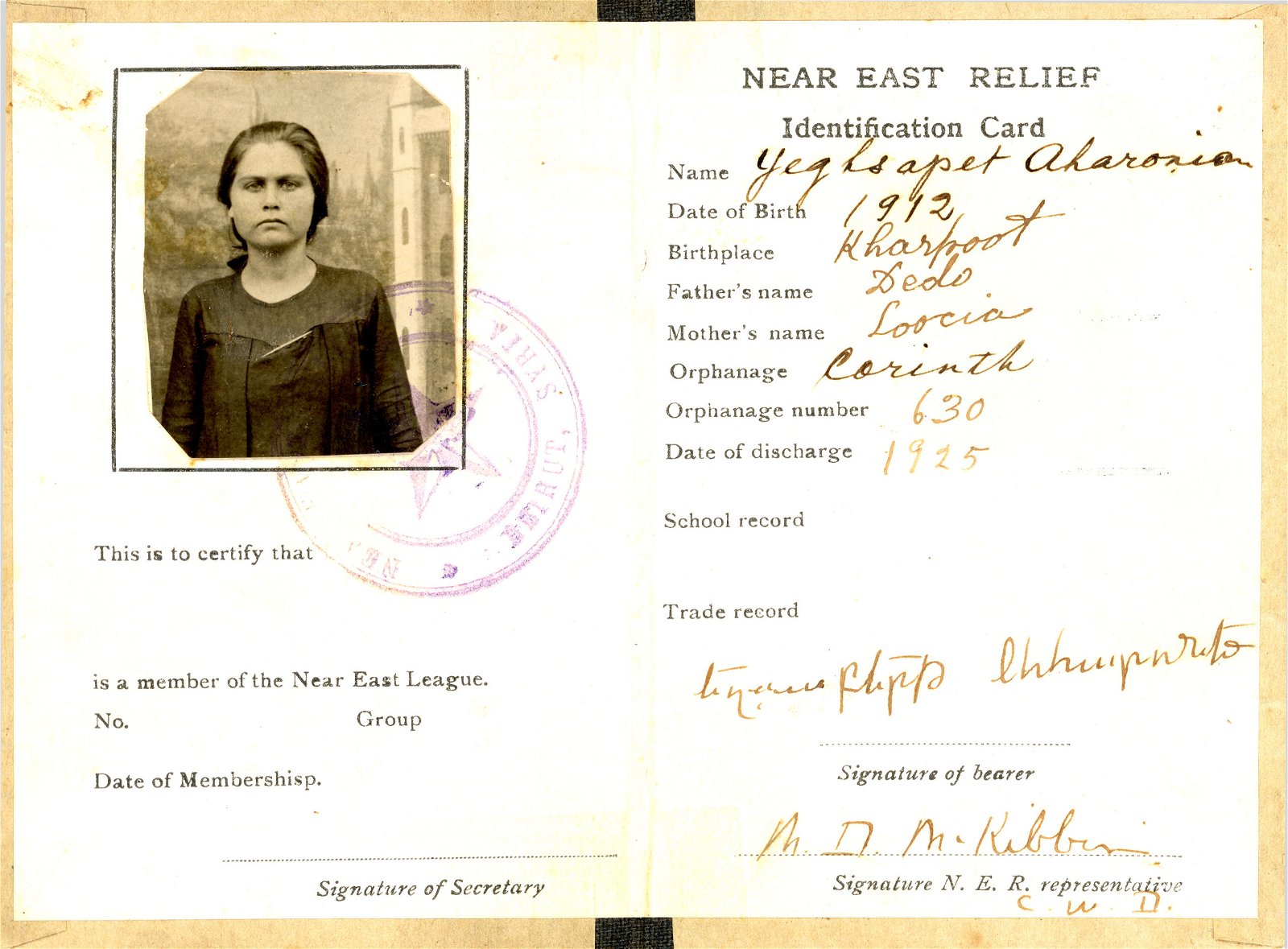

This is one of many family stories Harry Mazadoorian has shared with the Armenian Memory Project. His grandfather Garabed was imprisoned that year in Soorp Nigoghos Church and later massacred. Mazadoorian’s parents, Nigoghos and Yegsa Aharonian, survived the Armenian Genocide and resettled in Connecticut.

“My father remembers taking clean clothes to my grandfather while the men were imprisoned in the church,” Mazadoorian told the Weekly. “You can’t think of a crueler violation than to imprison the men in the church where they worshiped.”

The Armenian Memory Project is a visual storytelling initiative at the University of Connecticut that documents the histories of descendants of the Armenian Genocide. The project brings students into dialogue with members of the Armenian community to preserve the memories of the crimes committed against their ancestors and narrate their personal histories of trauma and survival.

The project was initially conceptualized by members of UConn’s Norian Armenian Programs Committee and Community Advisory Board in collaboration with NAASR, Project Save and Armenian Historical Archives in 2017-2018. Under the purview of the Human Rights Film & Digital Media Initiative at UConn, students created a short documentary film in a March 2019 course taught by Professor Anna Lindemann using archives from family historian Armen Marsoobian.

“Part of the mission of the Norian Armenian Programs is to educate the University of Connecticut community and broader community about Armenian history and culture and provide forums for Armenians and Armenian Americans to share knowledge and traditions,” said Zahra Ali, director of Global Partnerships and Outreach at the Office of Global Affairs.

In fall 2020, Marsoobian and filmmaker Catherine Masud guided students to produce a documentary film using materials from the Dildilian family archive and an oral history interview with Marsoobian. The students created graphics, animations and sound treatment to narrate the history of the Dildilians and recreate the Armenian community they lost to the Genocide using photographs and documents.

Marsoobian inherited his family’s vast collection of over 1,000 photographs and glass negatives, as well as official documents, letters, paintings and other artifacts. His family members worked as professional photographers in the Ottoman Empire, establishing a photography business in the Anatolian town of Sepastia. Their oeuvre crosses geographies and time spans, encompassing images of Ottoman Armenian life before the Genocide as well as images from their subsequent work in Greece and the United States.

“Members of my family lived more than a lifetime of these kinds of world historical events. They did a lot themselves to preserve material. When they write about it, they’re trying to preserve the story for the future,” Marsoobian said.

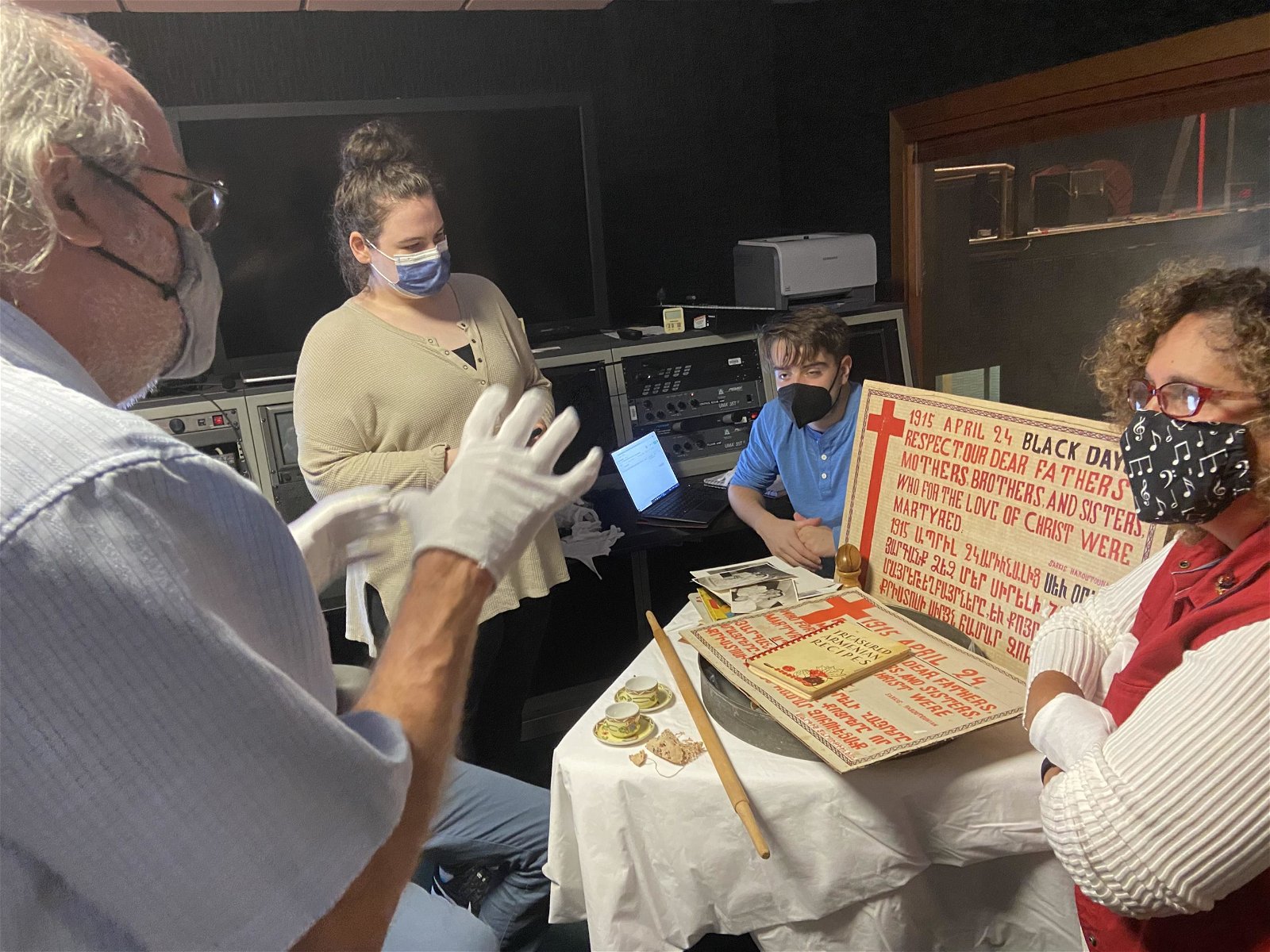

In the fall semester of 2021, students undertook the curation of a new archive of the history of the Armenian Genocide. During the course, students conducted and filmed oral history interviews with community members about their family stories. Community participants contributed family artifacts, such as photographs, government documents and personal belongings, which students digitized to create a collection of visual and audio testimonies.

By engaging with community members, students in the course apprehended the history of the catastrophic event through individual stories of suffering and survival. None of the students who have participated in the Armenian Memory Project so far have been Armenian. While students spent the first part of the course studying academic scholarship on the Armenian Genocide, they forged personal connections with this horrific history through the formation of a community archive.

“Many times I was taken aback by details I was being told about atrocities community members’ families faced,” said Jarred Reid, one of the students from last semester’s class. “To hear: my grandmother died on a death march, my great-aunt was taken and forced into marriage; to hear them with the personal connection highlighted or made real what we were learning from the textbooks.”

The oral histories and artifacts gathered by the students testify to the suppression of the history of the Armenian Genocide in official archives and expose the ongoing injustice of denial, according to Masud. Even when eyewitnesses to the event have passed away, the artifacts inherited by their descendants serve as evidence of their story.

“These personal histories, accounts and testimonies are a countervailing force in that attempt to erase or destroy a community or a history of a people,” Masud said.

Some of the community members participated in the Armenian Memory Project in order to preserve the memory of the Armenian Genocide. Mazadoorian said he feels an “obligation to those who endured the genocide, obligation to our current generation of Armenians and non-Armenians” and “obligation to future generations” to contribute his knowledge of his family history to Armenian Genocide scholarship.

“A genocide forgotten is a genocide continued. The last stage, the final and permanent stage of genocide, many people have said this, is when the genocide is forgotten. Then you might say the genocide is complete,” Mazadoorian said.

Indeed, according to Marsoobian, the story of the Armenian Genocide has not concluded. He hopes that storytelling initiatives like the Armenian Memory Project contribute to combating injustices around the world, such as the current conflict in Artsakh between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

“In Artsakh, they’re being portrayed as the aggressors, colonists and settlers. They’re not seen as the indigenous people of the region. Their culture is being destroyed. Their history is being rewritten. All of this is a continuation of the nationalist racist ideology that propelled the genocide in 1915, that continues to this day,” he said.

The Armenian Memory Project also narrates the psychological impacts of the Armenian Genocide on the descendants of its survivors. During oral history interviews, students discovered that the memories of human rights abuses transmitted across generations inform the identities of Armenians today.

“It’s almost as if it’s imprinted in your DNA. You may have lost some of the specifics. There may be a little embellishment that happens over time, but the essential memory remains in its impacts,” Masud said. “Silence is also evidence of witnessing, because the trauma may cause us to suppress that memory. We don’t want to talk about it, and yet it is felt by family members.”

The indelible effects of history on present generations motivate initiatives like the Armenian Memory Project that study and document family stories, according to Marsooobian. He has dedicated himself to excavating and curating his family archive for this very reason, since, in his words, “We are, in many ways, our history.”

“It’s reflective of a growing desire by people to understand their own identities, their own place in the world,” he said. “Who you are, where you came from, what your ancestors have gone through, all makes you a better person to be able to cope with the things that come up in your life.”

Students currently enrolled in the course are developing documentary films using the oral histories and artifacts collected in the fall semester as well as the Dildilian family archive. The films they produce will contribute to ongoing scholarship on the Armenian Genocide through a unique combination of digital technology, video testimony and family artifacts.

“There’s been an avalanche of materials produced about the genocide. You put that together with your family stories. There is a haunting story that emerges from it,” said Mazadoorian.

Editor’s Note, February 14, 2022: Information about the Armenian Memory Project’s early beginnings and notable collaborators was added per a request from UConn’s Global Partnerships and Outreach team.

Hi Lillian, I so appreciated reading this. My grandmother was from a small village just outside Kharpet, so I appreciated the mulberry tree story, in particular. But yes, I can think of something worse than being imprisoned in a church. My grandmother and some of her siblings were at school, in the next village. They arrived home to find all the men from the village were locked in the church and the church was set afire.