With the number of daily confirmed cases of COVID-19 continuing to rise––and with that, the death toll––calls on the government to reinstate draconian lockdown measures have grown louder. Still, the Prime Minister, who himself has tested positive for the virus, has resisted doing so. Instead, Pashinyan has kept his faith in strict adherence to social distancing protocols, which includes the wearing of masks in public spaces, the washing of hands and avoidance of large crowds.

But critics blame the authorities’ mismanagement of the crisis for the recent spike in cases, with specific accusations being lax enforcement of April’s lockdown (which the authorities have since tacitly acknowledged), and then lifting it before the pandemic was properly contained. Pashinyan repeatedly rationalized the decision to roll back most restrictions on May 4 as resulting from a pragmatic decision to walk the line between public health and economic recovery after it became clear that the global virus could not be contained before a vaccine became widely available. With WHO experts expecting COVID-19 to become a permanent part of life, it became clear that containment was no longer realistic, leaving mitigation to be the only remaining viable option.

Armenia, which was pegged as one of the better-prepared countries to deal with a potential pandemic before the current crisis began, has seen its social safety net stretched to the limits as it shuffled to provide emergency unemployment assistance to over 1.1 million furloughed and jobless people in the middle of the worst global recession since the Great Depression. In all, Armenia is estimated to have spent over $200 million in assistance since April – or almost three percent of its national GDP. They also managed to stabilize the currency, avoid stagflation and the sort of price gouging on essential items witnessed in many other Western countries.

Still, no country is equipped to freeze its entire economy indefinitely. As a small developing country, Armenia could simply not afford to continue the lockdown–or deal with the resulting social issues–according to Pashinyan. In early May, the Prime Minister explained his government’s new strategy as necessitating adaptation to live with the virus since, “I’m sure you’ll agree, the prospect of life under lockdown for the next year is not a realistic one.”

Needless to say, the government’s reliance on the general public taking on some agency in their own health by abiding by basic hygiene and social distancing protocols has been derided by opposition groups as an attempt to load off responsibility for an impending public health disaster.

While there is no question that Armenia is facing a severe stretching of its healthcare capacity as the coronavirus pushes more and more critically ill patients into overflowing ICUs, it isn’t clear just how lockdowns could curb the infection rate at this point.

With most estimates suggesting that the real number of infections in Armenia (based on extrapolations from similar cases across the world) is at least twice as high, at this point, the daily confirmed rate is no longer an appropriate indicator of the situation in the country. In fact, the higher rate is directly proportional to the number of tests conducted, meaning that more cases are now being registered simply because more cases are being found through better testing.

Thus, if a strict lockdown were called tomorrow, we wouldn’t be able to gauge its effectiveness for at least the next week. This would come at a time when the results of policies on mask wearing and stricter enforcement which have only been in force for a week start being felt. Moreover, it would likely only delay the pandemic rather than halt it.

At the moment, the vast majority of countries on the planet have opted for a variation of one out of two strategies for dealing with the pandemic: containment or mitigation. However, as the virus continues to spread across the globe, it’s increasingly clear that countries which have been successful in containing the virus have several commonalities: they are smaller, relatively isolated (on islands or peninsulas), and/or have extensive prior experience with pandemics. The latter is particularly true of New Zealand, South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam, all of which are in proximity to China, and thus, have been hit hard by previous outbreaks of H1N1, swine flu, SARs and so on.

For all other countries, whether it’s publicly stated or not, the strategy is mitigation. This means that public health authorities are trying to control as much as possible the rate of contagion in order to keep the hospital system from being overwhelmed until the virus either loses potency or mass inoculation takes place (either through a vaccine or herd immunity).

That’s what Armenia has been doing. As I have previously mentioned, the purpose of the lockdown in late March was not so much to eradicate the virus, but to momentarily slow the contagion rate enough for the healthcare system to cope with the expected influx of new cases. And over the weeks that followed, Armenia pulled off a truly remarkable achievement in re-purposing not only its entire medical network, but every institution in the country to buttress the effects of the virus. The Health Ministry made good use of that respite to retrofit 16 medical centers across the country and retrain thousands of medical personnel to treat infectious diseases. An entire state-of-the-art hospital was erected from the ground up to accommodate more patients. Combined, these efforts helped boost capacity to manage from several hundred cases in early March to over four-thousand by the first week of May.

And this sort of race to expand care capacity continues. Every time Armenia is near the brink, new professionals are trained, new hospitals are built or new wards inaugurated. This isn’t to downplay the seriousness of the situation. Armenia is in need of more medical equipment and trained professionals now as much as ever. But one way or another the virus will take its course.

As for the effects of stricter or longer enforcement of lockdown measures – that would only be relevant if the virus could be totally eradicated. But data from around the world shows that no amount of enforcement has successfully done so. Furthermore, infection rates are creeping back up even in countries which had successfully “belled” the curve. The question wasn’t “if” but “when.”

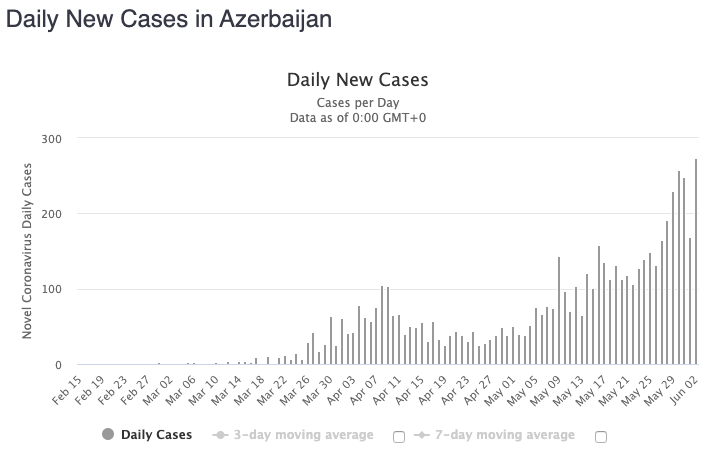

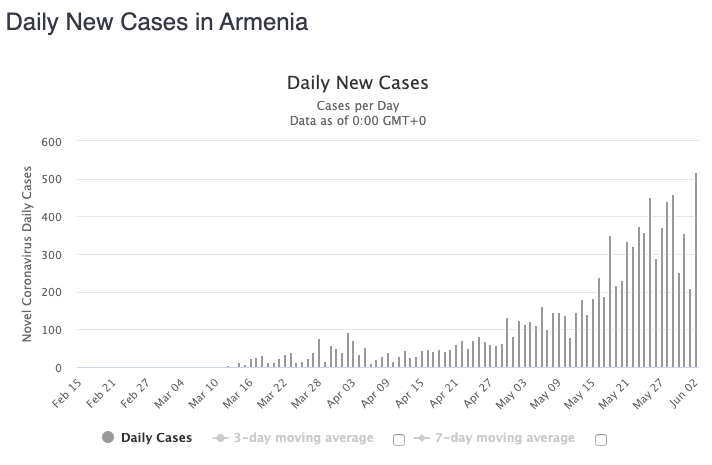

Since many critics have (unironically) cited Azerbaijan’s dictatorial use of police state tactics as an example of successful lockdown enforcement, it’s worth comparing the situation in that country.

As these two graphs of daily confirmed COVID-19 cases show, Azerbaijan briefly overtook Armenia in terms of cases in mid-April. Both countries saw “flattenings” of their curves at around the same time, but because Armenia lifted restrictions a week earlier, the numbers started creeping upwards, while Azerbaijan’s actually decreased.

But numbers for late May and early June suggest that Azerbaijan is catching up pretty rapidly in terms of new cases, with about a week’s delay––corresponding somewhat neatly with the date at which they reopened their economy.

I don’t pretend to be a statistician or an epidemiologist. However, there seems to be a pretty obvious observation here: so long as people move around, the virus will continue to spread, no matter how harsh or long the lockdown enforcement is. The only variable here is time.

Still, it seems quite clear that the current social distancing guidelines haven’t been enforced strictly enough. It’s certainly likely that had the government better prepared the population for social distancing before the lockdown measures were removed that the number of cases would not have surged so drastically, and faith in public compliance vindicated. Maybe enforcement could have kept some infected people at home who would have otherwise contributed to the infection. But as the Prime Minister has suggested, there aren’t enough cops to keep every single person in their homes. Ultimately, any critical analysis of government response here shouldn’t confuse this with holding back an enemy army: it’s more akin to holding back the tides.

I’m also not in a position to predict whether another lockdown at this point would do much to alleviate the situation in hospitals or cut the infection rate. It likely would, for a time. Maybe it could give the authorities time to set up more proper social distancing enforcement mechanisms? But I do know that when the next lockdown is eventually lifted, we’ll be back to where we are now: debating whether it’s appropriate to expect people to wear masks and refrain from gathering in large numbers until a vaccine becomes available.

Be the first to comment