The Opening

Over the course of ten months in 2014-2015, I traveled to Turkey three times. I went to reconnect with the land where my grandparents had been born and the places they had fled—my grandfather after the Adana Massacres in 1909 and my grandmother after the Armenian Genocide of 1915.

In 2008, Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) passed a law that allowed for the return of church and foundation properties. The medieval Armenian Cathedral of the Holy Cross on Aghtamar Island, Lake Van had been restored and opened as a Turkish national museum in 2007, but other buildings were being given back to the control of the Armenian Patriarchate and other organizations. In 2011 the Surp Giragos Church in Diyarbakir was re-consecrated after an extensive renovation. In March 2013, the Turkish government and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) announced a ceasefire, and in the summer of 2013 the popular uprising at Gezi Park added to the optimism about Turkey’s future. This was a period when many Armenians were traveling to Turkey, exploring their family histories and lost home places. It felt as though a door had opened for us.

During this time, Diasporan Armenians built relationships with like-minded people in Turkey as we came to terms with our shared communal history. For me, the Armenian Genocide—its mass violence, dispossession, exile, the efforts towards recognition and for redress—is a living history. It is alive also in the current predicament of the Kurds of Turkey. On more than one occasion I was told, “They had you Armenians for breakfast, and they are having us Kurds for lunch.”

I encountered the connective tissue of this history in the city Armenians call Dikranagerd, the Kurds call Amed, and that is labeled Diyarbakir on most maps. It is the unofficial capital of Turkey’s Kurdish region, or Northern Kurdistan. Names matter. What this place is called has been determined by a politics of domination and erasure. There is a long and ongoing struggle over which flag should fly from its ancient ramparts, and it seems flags are part of the problem.

An Occupied City

When our Armenian Heritage Tour bus drove into Dikranagerd in June 2014, we passed an enormous, fortified military installation and saw tanks parked in intersections along the road. Onno told me that a few weeks earlier, a masked young man had jumped over a fence at the local airbase, climbed the flagpole and pulled down the Turkish flag. This incident was widely reported, and the young man who had “assaulted” the Turkish flag was denounced around the country. There were calls for his execution, and at a demonstration against him in Ankara, people were shouting, “Turkey will be the graveyard of the Kurds.”

The entire city seemed to be filled with Turkish military installations, barracks, soldiers with guns, police with guns and private security guards with guns. It reminded me of the Palestinian West Bank, which I had visited a few years earlier. As we entered the old city, in addition to the markers of occupation, we saw young, unaccompanied kids roving the narrow streets. We were warned about beggars and pickpockets and were told we would have a security detail with us as we moved around the city. It was unclear to me what or who we needed to be protected from, but I didn’t ask.

We walked from our hotel in the historic Sur District accompanied by an armed guard, to the nearby Surp Giragos Church. Long wooden tables had been set up in the courtyard for a dinner prepared by local Armenian women. We were told this was the first Armenian church to be re-sanctified in Turkey since the end of World War I. Many Armenian churches around the country had been re-purposed as mosques, museums, banquet halls and other secular community spaces, but this was the first time an Armenian church had been re-consecrated for its intended use. We were also told that the neighborhood we were in was the old Armenian quarter, now the home of mostly poorer Kurds. It was called Gavoor Mahallesi, or Village of the Infidels.

Surp Giragos

Hirant, whose father had been a metalsmith in Dikranagerd, was on the team that negotiated with authorities and raised money for the reconstruction of the church. It was a political and legal coup that required a good measure of finesse, a great deal of money, and, according to Hirant, the distribution of many iPads and iPhones. The restoration of the church, which had long fallen into disrepair, cost around three million dollars. Amed’s Kurdish mayor had contributed one million dollars, and the other two million were collected from Armenians in Istanbul, the US and Europe.

On Sunday morning we walked from our hotel to Surp Giragos for the badarak, a long church service conducted in classical Armenian. The Acting Patriarch, who had flown in from Istanbul, presided. Vartan told me that after the sermon two converts—Armenians who had been Muslims for several generations—were going to be baptized, and a marriage would be officiated.

The church’s wooden pews were full, and the courtyard was bustling. People drifted in and out of the sanctuary during the service. The precincts were filled with a busload of tourists from Armenia, a folkloric dance troupe from Yerevan, a host of Turkish-Armenians who had flown in from Bolis and an assortment of Armenian Diaspora travelers, among them members of our Heritage Trip.

After the service everyone gathered in the courtyard for the dance troupe’s performance. When the musicians cued up a Dikranagerd folk song, lots of people jumped up to join the dance. It was a jubilant moment, but for some reason, it made me cry. I looked up to see some Kurdish kids observing us from a rooftop overlooking the church courtyard. One boy moved perilously close to the edge of the roof as he danced a little jig in time to the music.

Hirant’s House

After the performance, our group went to visit the vacant house where Hirant had lived until he was seven. He and his cousin Sevim were born there. The family had relocated to Bolis in the 50s because life had become too difficult for the few Armenian families who had survived the Genocide and remained in Dikranagerd. We opened the wooden doors, entering a courtyard where a tall tree still stood at the center. Hirant and Sevim reminisced about the old fountain and what each room had been used for when they lived there. On the second floor, we found a dove trapped in one of the bedrooms. People pulled out their cameras to get a picture of the bird as it sat above the barred window. Then I opened the window, and as the dove flew off, Mari, Hirant’s younger sister, and her daughter Christina began to weep. This was one of the strange effects of our trip—we could never predict what might bring one or another of us to tears.

Dikranagerd was our final stop; the next morning, we flew to Istanbul and then to our home countries from there.

The Destruction of Sur

I went back to Istanbul for a week in September 2014 with Columbia’s Women Mobilizing Memory Workshop and then returned to join Armenian Genocide Centennial events in April 2015. The solemn commemorative vigil attended by several thousand people on Istiklal on April 24 was a moving experience that deepened my profound, if conflicted, sense of connection. When I flew home, I had Turkish liras in my wallet and the idea that I would visit again soon.

But after the results of the June 2015 elections, when Erdogan’s AKP party lost its parliamentary majority and the pro-Kurdish HDP party made major gains, the political situation in Turkey turned ugly. The truce with the Kurds was broken, Kurdish cities and towns were put under strict curfew (which was a euphemism for brutal military incursions and lockdowns), and academics, among them some of my new friends, who had signed a peace petition were persecuted and prosecuted. It felt as though the door had slammed shut. With the July 2016 coup attempt and subsequent state of emergency, the situation grew only more repressive as tens of thousands were purged from their public sector jobs, and many were relegated to social death.

In the meantime, the Fortress of Diyarbakir and its gardens were designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in July 2015. In August 2015, Kurdish youth in Sur, allied with the PKK, had declared their region an autonomous zone and erected barricades to keep the security forces out. In September, the Turkish government issued a curfew. In early December, Turkish troops went into Sur’s narrow streets with tanks and assault vehicles. Tens of thousands of Sur’s residents were displaced. Military helicopters flew overhead, and when the tanks patrolled the streets at night, it was reported that their loudspeakers blared out anti-Kurdish and anti-Armenian slogans. One of them was, “You are all Armenian bastards.”

When the fighting was over, while the ancient ramparts were still standing, much of Sur had been flattened. Surp Giragos, which was reportedly used as a Turkish army base during the conflict, had been heavily damaged, but its walls and roof were intact. Rumors circulated that Turkish army personnel had pillaged the interior of the church when the fighting ended. Someone slipped into the church with a camera, and photos of the desecration appeared in all the Armenian newspapers. When I asked Hirant about his family’s house, he said it had been destroyed.

The Fate of the Church, The Fate of the Region

Turkish government statements suggested that Sur had been cleansed of terrorists and that it would be the site of a great urban renewal project. In reality it was a gentrification program aimed at changing the demographic reality of the old Village of Infidels. While Surp Giragos had been spared the worst, there were fears that what little else there was of historical value in Sur and six nearby districts that were also placed under curfew had been wrecked. The area was slated for modern “villa” homes that would be out of reach of the impoverished Kurds who had been living in the area. In 2018, the military curfew was changed to “a ban on entry to the construction zone.”

The chairman of the Surp Giragos Parish repeatedly requested the Turkish Interior Ministry pay for the repair of the church, the cost of which was estimated to be 700,000 dollars. After the bellicose destruction the area had suffered, it was unlikely that private donors would be interested in underwriting such a project. As of six months ago, the Interior Minister had agreed, the work has been undertaken by the same builder who did the original restoration and is either ongoing or stalled, according to two different reports from the area. An Armenian friend in Europe sent me some original photos of Sur taken from afar during his recent visit to Dikranagerd in October 2019. Sterile townhouses were being constructed over the razed neighborhood.

Meanwhile, also in October, the Turkish Army and its mercenaries, abetted by the current US administration, invaded northeastern Syria to create a so-called “security zone.” This dubiously named “Operation Peace Spring” was a campaign of ethnic cleansing against the Kurds of the region. The US had betrayed the Kurds, who had successfully battled ISIS and lost as many as 11,000 of their fighters in the process.

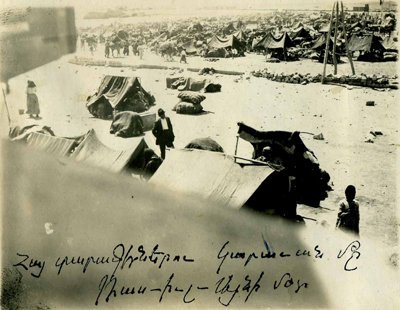

During the first days of the Turkish incursion, when the Syrian border city of Ras al-Ain was mentioned in news reports, I heard my grandmother’s voice: “We were thousands of starving orphans in a camp in the desert. I asked someone, ‘Where are we?’ And he said, ‘The name of this place is Ras al-Ain.’” On November 11, an Armenian Catholic priest and his father were murdered as they were driving from Qamishli to check on a church in Deir ez-Zor. The Deir-ez-Zor camps in the Syrian Desert were a major terminal destination of the deportations and the place where tens of thousands of Armenians perished. Within hours of the death of the priest and his father, ISIS released a statement claiming responsibility for the killings. For Armenians, over 100 years after our great disaster, even long after we were driven from and to these places, we are still there, joined now by the newly persecuted, the newly dead.

Nancy, thank you for the great article on the rarely reported events of the past few years and especially the “Sur Gentrification” photo. Of course, destroying the armenian neighborhoods erases evidence of our existence and is a continuation of the Genocide. Please shed further Sunshine on the destruction of Dikranegerd

Thanks, Garbis. It really is heartbreaking for Armenians and for Kurds. This article in the Guardian from 2016 has more photos of the destruction. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/feb/09/destruction-sur-turkey-historic-district-gentrification-kurdish

Wonderful report, Nancy. Among other things, it tied together accumulated rumors that had been confusing to me. So this is where Dikranagerd/Diyarbekir/Amed stands these days… Thank you.

Thanks, Markar. As I mention, there are varying reports about what is happening with Sourp Giragos right now. The area is still a “closed construction zone.”

Thanks, Nancy, for your excellent essay on the destruction of Sur. It’s even more painful because there had been a short period of hope in Dikranagerd before the crackdown and the leveling of the ancient neighborhood. The U.S. government’s continued resistance to recognize the Armenian Genocide has aided and abetted Turkey’s ethnic cleansing of the Kurds.

Thanks, Judith. There was a motto at Occupy Wall Street that comes to mind: “All of our grievances are connected.”

What a great article indeed. My eyes are leaking like the titanic. I met many survivors from that part of the world, and they told me about their childhood days. Stories, not happy but sad. Real stories and not fictions. They recalled the years of 1890’s and the early 1900’s. I am sure whoever reads this article will be reconnected to his/her roots because while fire turns to ashes your narrative turns ashes back to fire.

I am proud to know that we still have great Armenian authors like you. God Bless you.

Thanks, Michael, for the kind words about the writing. And what you say

about the sad stories reminds me of an Armenian proverb: Hayastan, vorpastan. (Land of Armenians, land of orphans)