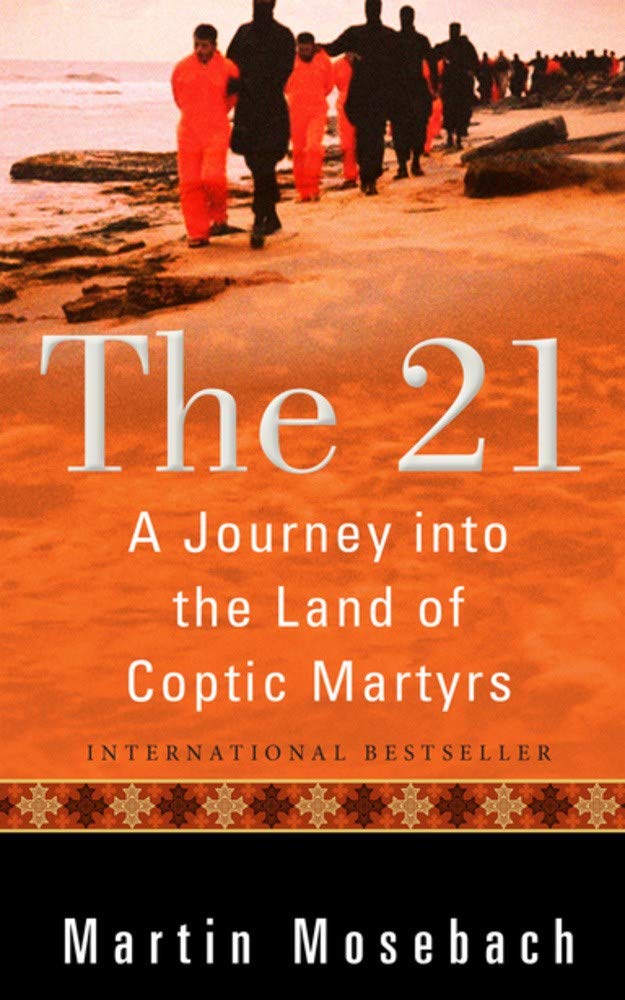

The 21: A Journey into the Land of Coptic Martyrs

The 21: A Journey into the Land of Coptic Martyrs

By Martin Mosebach, Translated by Alta L. Price

Plough Publishing House, 2019

272 pp.

$15.00 hardcover

On February 15, 2015, militants of the Islamic State (ISIS) beheaded 21 migrant workers on a Libyan beach. The scene of defenseless men in orange jumpsuits paraded to the sea became an instant symbol of many things: the cartoon-villain brutality of ISIS, the pointless destruction of Libya’s civil war and the ongoing persecution of Christians outside the West.

For how far the images of the 21 have spread, very little is publicly known about their lives. In The 21: A Journey into the Land of Coptic Martyrs, German journalist Martin Mosebach sets out to change that. In doing so, he brings to light a Christian community often forgotten by the rest of Christendom, the Copts of Egypt.

The 21 is a hagiography in the most literal sense—the 21 martyred migrants have since been named saints by the Coptic Orthodox Church. (Twenty of them were born Copts, and the last apparently converted to Coptic Orthodoxy a short time before his death.) In fact, the massacre of the 21 may be the first-ever televised martyrdom of any saint. In light of the significance of the event, Mosebach could not just write a conventional journalistic retelling of the events of February 2015. His book is a work of journalism, history, philosophy and theology, all rolled into one.

Mosebach’s reporting takes the reader through a kaleidoscope of scenes in Egypt and beyond. The vast majority takes place in el-Aour, the heavily Coptic hometown of the majority of the martyrs—a rural landscape of adobe houses that double as stables, concrete-domed churches and photoshopped icons of the town’s newly-canonized sons. Mosebach also weaves in scenes from the beautiful cathedrals of Samalut, the ugly migrant barracks of Libya, the majestic oasis monasteries of El Mohareb and the “garbage city” of the Coptic zabbaleen atop Mount Mokattam overlooking Cairo. As he concludes with the posh, sterile shopping malls of New Cairo, it’s clear Mosebach has had the modernizing Germany of his upbringing in the back of his mind the whole time.

The author wears his affiliation as a traditionalist Catholic on his sleeve. Mosebach pines for the days when Catholics took their liturgy and miracles as seriously as Oriental Orthodoxy does today. For the Copts he meets, the memories of Roman-era saints are as fresh and present as the memory of February 2015.

Mosebach’s assertion that “early Christianity is alive and well in their midst” seems to veer towards Orientalism. But the point he is making—and only a traditionalist Catholic could make it so well—is that Christian martyr culture predates the division of the world into “the East” and “the West.” Westerners could find it in their own tradition, if they bothered to look. Martyrdom is an organic part of the overlapping Egyptian and Christian worlds, just like the Copts themselves.

The military dictatorship in Egypt looms constantly, like the government soldiers and Islamist guerrillas who circle the cloisters of El Mohareb. The author hints at many Copts’ (and perhaps his own) attitude towards the Sisi regime and Muslim Brotherhood throughout the book, before finally revealing it in the voice of an anonymous Coptic hotelier. Even then, he is not just summarizing modern Egyptian politics, but telling the timeless story of any community trying to survive as a minority in an authoritarian system.

Looking from the perspective of an often-forgotten minority, The 21 avoids the clichés that journalism around ISIS often falls into. Neither Mosebach nor his sources are very interested in the topics du jour of Middle Eastern politics. Coming from a community that has never had a state and that had been under threat since the beginning of its existence, the co-religionists of the 21 martyrs can only afford to look at the bigger picture. Their discussions with Mosebach cut straight to the faith, resilience and memory that make us human.

Be the first to comment