Vocalist and world musician Khatchadour Khatchadourian is honoring his ‘mother tongue’, while reviving everything that Armenians have ever known about the sacred tradition of the soulful lullaby in his latest album Oror ou Nani.

“I wanted to liberate lullabies,” said Khatchadourian in an exclusive interview with the Armenian Weekly. “I’m showing the world that Armenian music not only has its own traditional aspect, but a deeply-rooted earthly, meditative aspect.”

Khatchadourian’s presentation of 13 Armenian lullabies is nothing short of a captivating and inherently divine experience. “These are sacred songs,” said Khatchadourian on the meditative roots of these ancient folk selections from the storied villages of Kessab, Moush, Van and Talish. While many Armenian lullabies are traditionally sorrowful reflections of a generation grappling with the immeasurable trauma of genocide, Oror ou Nani offers a more prayerful and spiritual space to recover. “Music is a way for me to understand the complexity of human emotion, to express it and to help it come to graceful, merciful, peaceful states,” said Khatchadourian on the meditative nature of his fifth album, which includes original compositions, unearthed 19th century poems and sounds from nature.

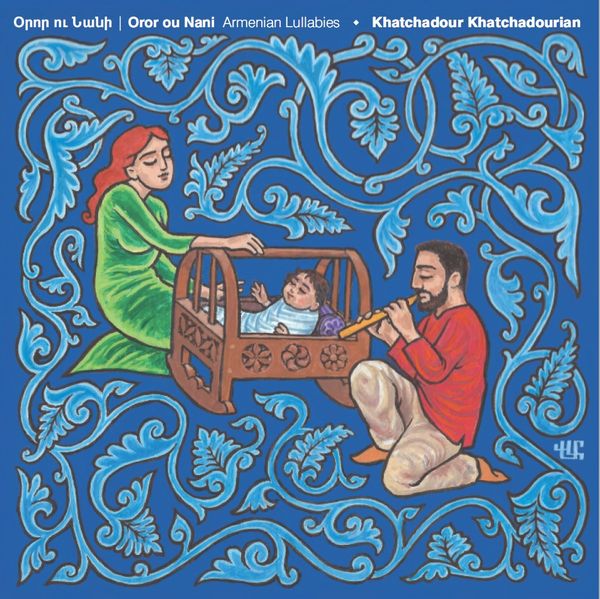

What makes Khatchadourian’s Oror ou Nani so unique, however, is that it is creating room for a man’s voice in a lyrical realm that has traditionally been dominated by women. “The best way to be partners in this world is to be actively participating in it,” he said on bridging the gender gap and creating the first modernized lullaby album performed by a male vocalist. Khatchadourian says this album is his way of encouraging males in the Armenian culture to relate to their children, to be more present in the daily ritual of bedtime and to explore their unabashed feelings of softness. Even the album cover illustration by Martin Vaneskeheian of Argentina made an important visual statement about tradition and family, unlike Taline’s Oror album which only depicts a mother with her daughter. “It showed where the father should be,” said Khatchadourian on Vaneskeheian’s beautiful and vibrant deliverable. “They’re in the picture together to partake in this sacred process of raising a unique being who is going to be crying all the time,” he added laughing.

Born in Lebanon, Khatchadourian grew up singing in the Armenian Orthodox church, which should not come as a surprise once you hear the sound of his voice. His God-given talents have the power to resonate with the faithful. Khatchadourian’s family eventually moved to Syria, where for seven years he performed with the Syrian-Armenian children’s choir Karoun. In 2001, he immigrated with his family to the United States, and shortly after, he started his studies at the University of California Berkeley. It was during this time of transition that Khatchadourian’s voice found some rest of its own as he was navigating the inner turmoils of the immigrant experience.

Ultimately in 2007, Khatchadourian would realize the healing properties of sound and develop a deep yearning to connect to his roots, compelling him to rediscover his voice with an incredibly mature and spiritual instrument. “The duduk brought the voice back,” he recalled. “Music was calling me. The duduk, the voice of the duduk, the sound of the duduk was very attractive, because it spoke to the level of emotions that we carry as a culture.”

The duduk brought the voice back

The indigenous Armenian instrument played a central role throughout this musical journey. In track one, the duduk serves as the familiar tune for Komitas Vartabed’s Kaqavi Yerq against a lively electronic background of bird sounds. We hear Khatchadourian play the duduk again halfway through track eight’s medley of Taroni Oror ou Anoush Qnik, an ethereal adaption of a folk lullaby from the region of Kessab.

Khatchadourian’s heartfelt lullaby renditions are soft and pronounced, a seamless and calming sequence that has been carefully arranged to follow a rather mysterious and even scientific demonstration of the sleep cycle. Khatchadourian says he was incredibly tuned into the order of the album’s tracks after spending a great deal of time researching sleep with his team. The tracks were ultimately organized to transition from a pair of lively songs to more meditative and calming selections.

Oror ou Nani was a humbling project in many ways, said Khatchadourian, who had to bring himself to a certain state of awareness in his distant understanding of parenthood and imagine the love of a parent-child bond that’s strengthened at bedtime. During studio recordings, he said he pretended that he was cradling a baby and moved his body accordingly. “If my body is tight, the voice will be choppy,” he explained. He worked closely with his producer Todd Boston to ensure these moments did not feel rushed and that they maintained the softness of the track.

Oror ou Nani also aligned the visions of several important people in his life—two of them happen to be women and Khatchadourian’s “equals.” His girlfriend of several years Hasmig Tatiossian along with new mom and dear friend Sirouhi Torkomian were instrumental in not only convincing Khatchadourian to lend his voice to meet this need for a special set of lullabies in the Armenian Diaspora, but also insisted that the team adopt a Kickstarter campaign to garner support from the Armenian community and beyond. The fundraising platform generated interest from more than 200 financial supporters and a loyal online following (@dudukwhisperer).

As for me and my family, Oror ou Nani has been part of my daily routine with my three year-old son Alik for several months now. We have found that the lullaby album is not strictly tailored for younger audiences, which was one of Khatchadourian’s aims. Everyone deserves rest, making this a universal journey for anyone willing to seek it. “We are far more complex human beings than office work,” explained Khatchadourian. “To rest is to be able to get to the realization more regularly that you are a beautiful being. You are complicated. You are a vast being,” he added.

Oror or Nani also inspires listeners to remember. When I heard Khatchadourian’s initial keyboard notes in track six Qoun Yeghir Balas, I was overwhelmed with gratitude and instantly transported to indelible childhood memories with my paternal grandmother Eveline, whom I call Nani—an ironically common sound that denotes ‘lullaby.’ When she would sing that specific song, she used to make us cry with her melancholy rendition. Today, decades later, I have shared Khatchadourian’s modernized composition with my grandmother, who fondly recalled those tender moments as well. “This was my song to all of you,” she said to me in Armenian as she sang along.

Khatchadourian says his album projects are not just musical presentations, but they also bring people together. It’s part of a communion, he says, that supports integration and connection in an increasingly noisy world. “I’m doing this to generate certain states of awareness, but not to tell the person what to feel…to tell them they should and they’re invited to feel intensely, but to let them process whatever they process.”

This summer, Khatchadourian will be studying in Armenia for a voice and duduk intensive. He believes in allowing sound to be his teacher, giving rise to the nature of the duduk and the unique way it works the human body and builds an unmatched capacity for sustained singing. “Sometimes, something draws you in and you don’t know what it is until you follow your heart and then you untangle the reasons.” Khatchadourian tells the Weekly he has plans for an Armenian meditations album, as well as a possible tribute to Komitas Vartabed on the 150th anniversary of his birth.

So how do we purchase?

Khatchadour’s website is linked in the article…

khatchmusic.com

“Khatchadourian’s family eventually moved to Syria, where for seven years he performed with the Syrian-Armenian children’s choir Karoun”(Aleppo). The conductor of the choir Karoun, was Boghos Abadjian. “Kez Hamar Hayassdan Souriahay Ganants Hantsnakhoump” of Aleppo, adopted the choir & took care of all the necessary needs (costumes, selling tickets of the performances, watching the children during the rehearsals & the concerts etc.. Khatchadour may remember the ladies of the committee, who even took care of the children during the picnics organised as a reward for their year long “hard work”. 🎶