This article is the first in a two part series written by Armenian Weekly columnist Lalai Manjikian. Part II will be posted tomorrow, March 25. To read part two, click here.

It is that autumn season again in Montreal when fallen leaves brighten the city. Nothing burdens me right now, as I feel the earth’s cold moisture spread across my knees, staining my newly washed jeans. Instead, I form abstract clusters of yellow, red, and brown as I collect the leaves on the ground. This act soon becomes the free rearrangement of dampened earth colors on a grass canvas against the brisk November wind.

Time slows down only when I kneel on the earth’s surface in such close proximity to the humid grass. I am reminded of a gentle pace, the solid entrenchment, and the idea of a connection. My mind begins to trace a map of the roots and the routes that brought me here. I think of these journeys every time there is work to be done in my father’s urban garden miles away from his ancestral village of Karadouran near Kessab, Syria, where he learned to work and reap the land as a young boy.

I watch as my father methodically turns the soil so that, come springtime, he can plant new roots. He works with a serene seriousness, unmistakably carrying the physical traits and movements of his own father of whom I have but a few distinct memories from my visits to Kessab as a child. These images of baboug, my grandfather Hovsep Manjikian, are beginning to fade, barely kept alive through photographs that still leave many things said, heard, or felt outside the frame.

Those childhood visits to Kessab left a lasting impression on me. I can recall the fragrances of boiled quince or grapes on burning wood, playing on the swing under the shade of vivacious grapevines, and long walks through the apple orchards. Most particularly, I remember how baboug would put his transistor radio up to his ear to listen to the news with the volume at its highest setting. Because he was hard of hearing, my father had sent him a hearing aid from Canada, but it still required full volume on the radio. After baboug passed away in 1994, my father inquired about that hearing aid, hoping that someone else in the village could make use of it. It then emerged that my grandfather had been buried with the hearing aid – a literal posthumous union of technology and body.

Baboug loved tomatoes. Watching him chew fresh tomatoes with such appetite has left an imprint in my mind. I remember how he would eat a simple dinner, consisting of a tomato and cucumber salad, toneer-ee hatz (village bread) and oghee (ouzo). The distinct scents of warm hatz and potent oghee filled the kitchen and veranda of the ancestral home. As he ate, small beads of sweat would trickle through the finely drawn gorges of his sun-kissed face. Why did he perspire, I wondered, despite the cool gentle breeze that rarely stopped blowing through the veranda?

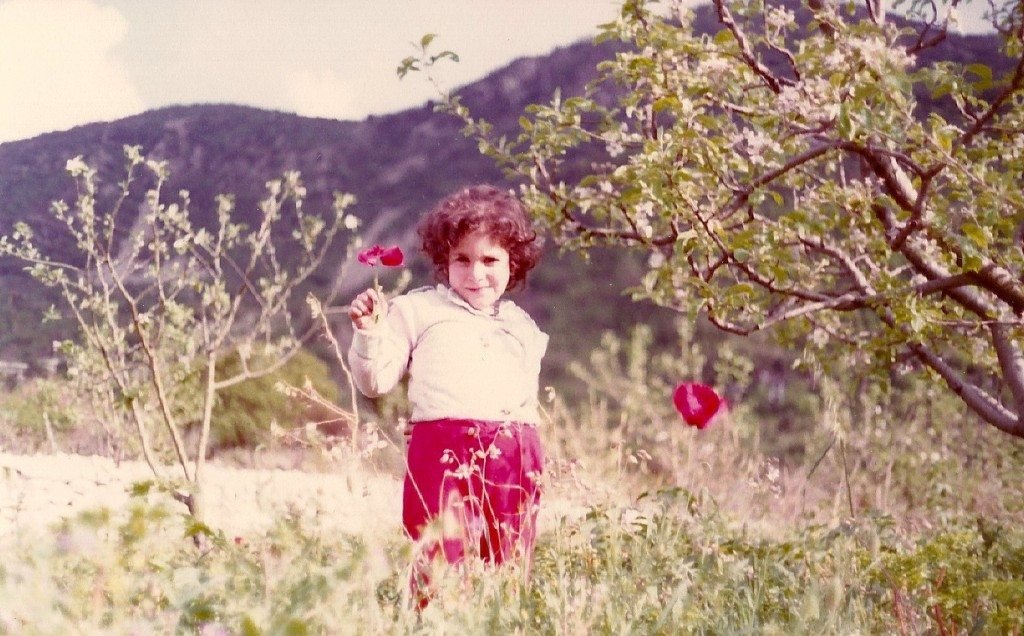

The village of Karadouran is where, as an infant, I learned how to walk. A grainy photograph shows me in a red-and-white polka-dot dress. I was holding my older brother’s hand, as I practiced how to take one step at a time. Now I think back on that reality and I am comforted to know that my first steps in life were on land where thick roots grew deeply. Shortly after those first steps, I would be flung, like many Armenians, amid the unceasing flows and unfixed realities that living in the diaspora entails.

To this day, Kessab and its surrounding regions retain a significant Armenian population. A drive down a narrow, winding road through towering mountains leads to my father’s village of Karadouran, which is located close to the Mediterranean Sea. The previously untamed, mountainous backdrop is now being populated with modern villas alongside ancient stone houses.

The most valuable resource in the area is the fertile land. Villagers have subsisted mainly by selling their harvested produce from that land, initially with non-mechanized and rudimentary processes. Baboug worked on that land all his life, at first growing tobacco to fulfill the Syrian government agricultural quotas, and later harvesting and selling apples.

Karadouran is also where my grandmother, Kalila Yaralian-Manjikian, lived until she quietly passed away on November 2011 at the age of 104.

I was fortunate to have visited Kessab in October 2007 to celebrate my grandmother’s 100th birthday. As an adult, I was able to form new memories from listening to her wisdom, laughing with her, answering her questions, hearing her answer my own questions that I had about her life, and hugging her. I enjoyed her sense of humor and inquisitive mind first-hand. I was in the presence of a century lived, and Kalil nene inspired me profoundly with her strength and resilience.

She was unquestionably the doyenne of the village. Visitors, friends, and family, from near and far, would always make the mandatory stop to see Kalil nene, to receive her blessings, to answer her questions of what they were up to and where they were in their life—and this, until her very last days. Even outsiders were taken by her degree of lucidity and her life trajectory. Foreign filmmakers who managed to reach this remote area sought to preserve her and her words for posterity.

When I last saw her, I was amazed by her self-sufficiency and mobility at her advanced age. Her level of awareness, her intact memory that recalled the finest of details, her sharp and curious mind, and her wit were all remarkable. At times, she had critical words to offer and was very categorical about what she wanted. Most of the time, she would just voice her opinion and then let it go with a simple “Eh, took keedek” (you know best). She always knew the whereabouts and status of everyone in the village, and those who had gone abroad.

Named after the Biblical Galilee, Kalil nene was born in Karadouran in 1907. When she was about one year old, her family was forced to flee the village during the time of the Adana massacres. In 1915, her family was forced to flee again during the Armenian Genocide. They made their way to Damascus on foot and then joined a caravan to the Salt and Mahas regions in Jordan. It was in Mahas that Kalil nene’s father passed away.

In 1918, when the British army entered Jerusalem, her family relocated there. She bore a tattoo with a cross and the year 1918 as a memento of her time in Jerusalem.

Later in 1918, her family moved yet again, this time by train, to Port Said in Egypt to join other displaced Armenians from Kessab, Musa Dagh, and other regions. It was in Port Said where Kalil nene learned the Armenian alphabet.

At the beginning of 1919, the Armenians residing in Port Said began either to resettle in other regions or to return home. Kalil nene’s family was taken by train to Aleppo, Syria, where horse-drawn wagons took them to the region of Antioch. From there, they made their way back to Kessab, and then finally to Karadouran on foot. The Armenian population of Kessab that survived the mass killings and deportations was then able to begin rebuilding their destroyed homes and villages.

In 1927, Kalil nene married my grandfather. Over the next few decades, they raised three children while another World War ensued, and the Middle East experienced numerous upheavals. Life continued in rural Karadouran at its usual pace however, with small doses of modernity gradually infiltrating their everyday existence.

When Kalil nene turned 100 years old, one of her grandchildren asked her, “What is the secret to living so long?” She replied simply, “Lead a clean life.” There is a multitude of ways one can interpret this eloquent statement.

During her 100th birthday celebration, she refused all assistance. On her own, she climbed down the 10 stairs of her home, and then walked quite a distance from the car to reach the “honor table” in the restaurant where her birthday was held. Everyone watched admiringly as she took one solid step after another using her two wooden canes.

She was a member of the Armenian Relief Society for 80 years and received official recognition for it. She was also a supporter of Armenian schools in the Kessab region. She even attended the opening of a new school building not long before she passed away, having been a contributor to the funds for the school.

How did she live such a long and healthy life? Was it the clean mountain air, her genetic make-up, the years of arduous physical labour in the village, or the fact that she was a strict vegetarian and preferred to eat grains such as bulgur and lentils? Perhaps all of these factors, combined with her overall positive and healthy outlook on life and her sense of humor, contributed to her longevity.

Kalil nene witnessed the beginning of the unrest in Syria in early 2011, but she passed away before the crisis intensified. I wonder what nene’s reaction would have been had she continued to witness the bloodshed unfolding in Syria. She was fortunate to have avoided yet another – a third – forced displacement. Her death was timely in that sense. How do you displace elders who have spent a lifetime building their dwellings, stone by stone, day by day?

During the ongoing upheavals in Syria, countless citizens, including some Armenians, have bravely salvaged what they can and have sought to live a semblance of a “normal” life, given the difficult circumstances. Many have fled or may be forced to flee from their homes, which could deprive Aleppo, Damascus and Kessab of a rich historic Armenian presence. Those who are displaced may be forced to endure the challenges of establishing a new life, and the uncertainty of whether they can return home again. In the meantime, they will inevitably grow new roots wherever they find themselves.

As the crisis continues in Syria, indiscriminate killing and violation of human rights are becoming as accepted as breaking bread. Syrians of various cultural, religious, and political backgrounds face dispossession on far too many fronts – the loss is unimaginable. Amid this anguish, the story of the Armenian diaspora also continues to be written as long-standing communities suffer and bleed. Armenians are like nomads who are condemned or blessed to carry real and figurative pieces of their homes, in order to re-build new ones, amid the unrelenting movement of people around the globe by force or free will.

Despite being forcefully displaced twice, Kalil nene had still succeeded in returning to the ancestral land, where she was born and raised. She tirelessly worked that land and was buried there after reaching the milestone of a century. Life came full circle for her. Living within a diasporic reality—to be born and raised on, and to work and die on one’s ancestral land close to one’s roots—is indeed a rare gift.

Back in Montreal, time slows down again for me momentarily as I stare out at my father’s garden. I watch as the painted leaves are pushed by incessant whirlwinds across the fence into the neighboring yard. The autumn sun warms my face as I continue to contemplate my Kessab origins and daydream of visiting that land once again…

Lalai Manjikian holds a PhD in Communication Studies from McGill University (2013). She currently teaches in the Humanities department at Vanier College in Montreal. Lalai writes and teaches in the areas of human migration, refugee social exclusion and inclusion, the ethics of migration, media and migration, intercultural communication, and diaspora studies. She is the author of Collective Memory and Home in the Diaspora: The Armenian Community in Montreal (2008). Lalai writes a monthly column, titled “Scattered Beads” for the Armenian Weekly.

Dear Lalai,

Thank you, it’s very touchy, impressive and learning subject.

God bless you, your Dear family and your mission.

You have different feeling and love towards human being.

When love is missing than the devil taking place.

Respectfully,

Bedros Zerdelian

Dear Lalai,

I was terribly touched by your expression

of love for your ‘Nene” and Kessab. You have

Described just what so many of us have

Experienced with our sheltering and encouraging families. “Nene” and you are

Living examples of our village and familial

Past, combined with our New World sensibilities. You came from a tree with deep

Loving roots. I hope Kessab will always be a

Part of you. I hope Armenians will return and

Believe in their lands, and they will never experience the slaughter house again. I pray

For peace.

Julie Barsoumian

Superbe article Lalai. Merci! J’ai hâte de lire la suite.

A few years ago I enjoyed another trip to Syria from Jordan, where I worked as an American archaeologist. I asked our guide, a professor friend of mine whether I might leave the group to visit Kessab, where my former husband’s family originated. In his 90’s Grandpa Sam Giragosian had talked about Kessab time and time again. I was wished a safe trip. and I set off in an SUV driven by the son-in-law of our Syrian guide. I searched for a church where Sam had been pastor. One churchyard was locked, so I went to the adjacent house. Two elderly women greeted me and told me a Giragosian family lived next door! I was welcomed into the Giragosian home. My host did not know Sam, but he opened a book next to his telephone and showed me the name of my former husband and the names of our three children! I was amazed that in this small village in Syria I would find the names of my children! I took photos of the Giragosians and the village to share with relatives back in the States. What a fabulous memory I have of that day in Kessab. May all the Kessab families find peaceful lives today and in the future.

I am a physician and public health practitioner from Armenia, a decent of Kessabtzis-my grandparents and parents moved to Soviet Armenia from Kessab in 1947- but hence, I feel the deep connection with Kessab from the stories of my grandparents and parents and always had been cherishing the dream that one day I will visit our home…It is so much difficult to express what I feel now- almost a feeling similar to what we all feel about 1915. Thanks for a beautiful and touching article, Lalai.

Abris Lalai

I am so proud of you.It is exceptionally well written .

Lalai you write with such eloquence. You have documented your Nene’s life so beautifully! Thank you for sharing this heartwarming story with us all.

Dear Lalai,

Part one,Part two,2 beautiful articles. Written with eloquence, love and soul. Subtle humor, sensitivity .You touched our hearts with your unique way of expression and filled us,Kessabtzis or not, with Hope and Faith.

Thank you,looking forward for your next articles!!!

Lalai,

I just wrote a poem about what is happening in Kesaab, and I want to use your childhood picture to illustrate it.

Thank you for writing this.

Poem below:

Don´t show me

the coffins of children

with that deafening

orchestral scoring

My sadness

doesn´t need a soundtrack

What do you want from me

masters of montage

and emotional chord

strikes

Don´t let me hear

the Armenian tongue

of my school days

from the mouths of children

displaced

bombed

their lives

forever raped

the familiar words

Vah

Tbrodz

A sound,

deadly,

Are you afraid of the bullets? The filmmaker says

But you still go to school

Nods from the two girls

in my tongue

in my words

that I have

forgotten

though they live inside me

Syria

my grandmother´s cradle

before she sailed on

the Atlantic

My flesh and blood

The people with the names

I do not know

The churches

that turned to rubble heaps

The prayer

we used to sing at school

it makes me cry

though I am not religious

and our god

is not mine

The prayer

Lord in Heaven

protect us

bring your kingdom to us

Our Kingdom lost

and April is coming

It will be

a hundred year soon

A hundred years

and nothing has changed

Someone´s grandmother

in Syria

has been born

and her mother

is smuggling her

right now

to save her life

and cross oceans perchance

so that I

can have

my blissful life

in a quiet place

somewhere

Syria

Syria

Syria of my heart

hurt over the scar

the pillaging

childslaughtering

the Deathland

over the Genocide

Chère Lalai

Vous m’avez tellement émue surtout de ce qu’arrive à notre cher Kessab, à ses habitants, il faut que le monde entier lise, sache qu’il y a un peuple qui ne demandait qu’à vivre avec sérénité dans son pays natal, ils sont persécutés, harrassés. Merci Lalai de votre histoire je souhaite que vous puissiez continuer à écrire, merci à vos parents de vous avoir mise au monde et de vous avoir élevée dans la norme des valeurs humaines.

Sossy Piloyan

Than you for writing this article, you make me proud as a Manjikian. I also visited kalil nene back in 2007, in kaladouran. She was in good health then. God rest her soul.