Special for the Armenian Weekly

The following quote contains what reportedly happened to Fatma Tokmak, a Kurdish woman from Sirnak in Turkey’s Kurdistan, when she was arrested in 1996: “They blindfolded me when they put me in the police car. I was holding Azad in my arms. The police officers sitting on my left and right beat me on the way to the Anti-Terror Branch of the Istanbul police department. I was exposed to torture and sexual abuse for 11 days there. They gave me electric shocks many times.”

Tokmak was 21, and her son Azad was two and a half years old when they were taken to the anti-terror branch of the Istanbul police department. The police covered Tokmak’s eyes while they interrogated her. She was stripped naked, beaten, sexually abused, and threatened with rape. Fatma Tokmak said her tormentors hung her from a hook and gave her electric shocks.

She was tortured ferociously while under arrest, but that was not enough for her torturers; they also tortured her little son Azad in order to pressure her to speak.

A huge problem that the state authorities ignored was that Tokmak could not speak Turkish when she was arrested, nor did she know how to read and write in any language. The police forced her to put her thumbprint on testimony that she could neither read nor understand.

Young Azad was also stripped naked and forced to touch his mother in unseemly ways. The torturers extinguished cigarettes on his hands and back. He was kicked and sexually abused, as was his mother. All these torture marks were documented by the Turkish Foundation for Human Rights and the Istanbul Chamber of Medicine.

Tokmak said that her greatest torment was watching the police torture her child and then take him away from her.

Fatma Tokmak was born in 1974 in the Kurdish province of Sirnak in Turkey’s Kurdistan. Having lost both parents as a child, her sister raised her. She got married very young. Her husband was continually pressured by the state. She was seven months pregnant when her husband finally joined the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Tokmak named her son Azad, which means “free” in Kurdish, hoping that he would be free one day. But when the house where she was staying as a guest in Istanbul was raided by special police units, her life came tumbling down.

“I understood Turkish but could not speak it. They thought that was the attitude of a PKK member, so they tortured my son before my eyes. They extinguished cigarettes on his back, neck, and hands. The child screamed in pain. Every time he screamed, a part of me died. They said, ‘Azad is not your son. If he were, you would speak.’ They lay me down on the ground naked and stripped my son naked, too, and threw him on my body as they swore at us viciously. Then they threw us into a cell,” she said.

“I had been tortured so badly that I was not able to take care of my son. My son needed to be fed, and his diapers had to be changed. He was in such a bad situation that the torturers said that if he died at the anti-terror branch, he would be a propaganda tool for the PKK. They tried to force me to change his name and give him to a child protection institution. When I refused, they tortured me even more. The police beat me and forced me to put my fingerprint on my testimony. When I was taken to the Besiktas courthouse, I could hardly stand. I was arrested and put in the Gebze Women’s Prison for being a member of the PKK and recruiting members for it.”

Much of this shattering narrative we know because Zeynep Kuray, a journalist who was staying in the same prison in 2013, interviewed Tokmak there and brought her story to the world. Kuray also reported that Tokmak had difficulty breathing, could not climb stairs, and stayed alive only because of the medicine she took daily.

Eren Keskin, Tokmak’s lawyer, said that she found Azad at a child protection institution and struggled for a month and a half to get him back to his mother. Keskin said that when she saw Azad, she understood that the bruises on his soul were deeper than those on his body. The lawyer did everything she could to return Azad to his mother.

Tokmak developed a heart condition as a result of the physical and mental trauma she endured in prison. She was eventually released pending a trial in 2006 because of the medical reports on her health after 10 years of incarceration.

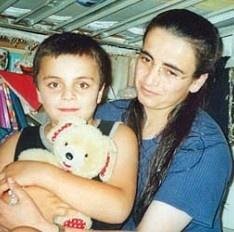

At last, Azad and his mother were reunited. Tokmak started working at a public institution and settled down to make a life for herself and her child. For the first time in their lives, it seemed that the future might not be so terrible for mother and son.

But Tokmak’s trial dragged on for four years, and she was sentenced to life imprisonment for “impairing the territorial integrity of Turkey”—whatever that means! The prosecution had no concrete evidence against her of any kind. Tokmak is still in jail today. She suffers from very serious heart illnesses. Her two cardiac valves no longer function. Tokmak must be released to a hospital to undergo an operation, but the authorities refuse to release her from Istanbul’s Bakirkoy Women’s Prison.

Azad is 19 years old. He had to drop out of school when his mother was rearrested. He now lives with an aunt. Azad is doing his best to save his mother’s life. He launched a campaign to demand the release of his mother by sending an open letter to former Turkish President Abdullah Gul demanding her release.

Eren Keskin submitted a petition to the Forensic Medicine Institute whose opinion is required to obtain the release of a sick inmate from prison. Although the institute gave a report documenting Tokmak’s illnesses, it also stated that she could survive life in prison. Tokmak, therefore, continues to languish in jail.

The insistence of the Turkish state on not solving the Kurdish problem by using democratic and peaceful means, as well as the inhumane decisions handed down by the biased Turkish judiciary, have stolen the life of yet another Kurdish mother and child.

Fatma Tokmak’s life embodies the horrible mistreatment Kurds have had to endure by the Turkish state: denial of rights, violence, torture, unlawful arrest and detention, and unending humiliation. The government might also have killed her instantly, just as it has murdered thousands of other Kurds, but instead, Tokmak has been forced to experience a slow death in prison—for the crime of having been born a Kurd.

‘In the 1990’s, every Kurdish woman who was detained was sexually abused and tortured during interrogation. That was the kind of treatment that the Turkish state thought the Kurds were worthy of.’

Tokmak is not the only Kurdish woman exposed to appalling torture in jails in Turkey. “In the 1990’s, every Kurdish woman who was detained was sexually abused and tortured during interrogation. That was the kind of treatment that the Turkish state thought the Kurds were worthy of,” Keskin said.

Now, about two decades later, Turkish jails are still filled with Kurdish political prisoners. Between 2009 and 2012 alone, hundreds of Kurds, including politicians, activists, and elected mayors, were arrested.

Contrary to the overall misperception of western politicians, the issue of Turkey’s Kurdistan is not an issue of “Kurdish terrorism.” If anything is to be condemned as the root cause of this problem, Turkey’s treatment of the Kurds, which has included massacres, prohibitions against the use of Kurdish, forced assimilation, and displacement, should first be condemned.

It has been 18 years since Tokmak was first arrested. During all this time, her torturers have been enjoying their freedom with impunity, while she is decaying day by day in a prison cell.

To watch Al Jazeera’s interview with Eren Keskin and Fatma Tokmak, visit www.youtube.com/watch?v=mdPzS-dI8WM.

Tokmak’s case as well as as other documented cases of Kurdish women sujbmitted to torture, forced assimilation ands other inguman treatments, must be brough to UN tribuabls,namely, the Committee against Torture, Amnesty International and other Women’s Defense Conventions. I think Turkey is sigantory of these treaties.

aline dedeyan (Geneva)

It is a human tragedy like many others caused by the “Democratic, freedom loving, peaceful and Turkish Republic”. A “Secular country that can be used as an example for other Moslem countries” according to the official US Government. I don’t think that this article/story belongs in an Armenian newspaper. We Armenians know more than enough about Turkish “civilization and culture”. This and similar articles belong in US and European papers so that their public knows more about Turkey, a country that many want to see join the European Union. Something that if it happens will mean the end of Europe and its civilization as we know it. Europe, America and the world, wake up and know who real Turkey is.