Many historians and genocide scholars have regarded the 1915 Armenian Genocide as the model for all subsequent genocides in the 20th century. It is critical to examine the strategies used by the Ottoman Empire to massacre Armenians in the early 1900s, as we can recognize identical patterns three decades later in the Palestinian Nakba.

Cultural annihilation

The Armenian Genocide went beyond a campaign of mass, indiscriminate murder; it was a complex plan to eradicate all vestiges of Armenian culture, identity and traditions. Sultan Abdul Hamid II, the 34th sultan of the Ottoman Empire, played an integral part in advancing the frequency and severity of cultural erasure of Armenians. He was hyper-fixated on eradicating anything related to Armenians in his empire. He gave strict orders to prohibit the usage of the word “Armenia” in Ottoman newspapers. He additionally abolished Armenian schools and prohibited the introduction of books about Armenia. He even went so far as to rip out the maps in a Bible owned by Clarence Ussher, an American physician and missionary, since these maps recognized Armenia (Balakian, P. 2009. The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America’s Response. Harper Collins).

Another example of Armenian cultural erasure was the forced conversion of tens of thousands of Christian Armenians to Islam. Abducted Armenian children were inserted into Muslim families, while others were given the option of conversion or execution. Christianity is central to Armenian national identity, and the Ottomans deliberately sought to eliminate a portion of culture that has preserved Armenia in the face of vast empires for millennia.

Cultural erasure was also a central component of the Palestinian Nakba in 1948, with the destruction of over 530 towns and villages by Israeli forces (Pappe, I. 2007. The ethnic cleansing of Palestine. Simon and Schuster). This widespread demolition went beyond physical loss; it systematically erased the cultural, historical and social fabric of Palestinian communities. The villages, each holding centuries of history, embodied unique traditions, dialects and memories that connected families to their land. By eliminating these villages, the Nakba obliterated spaces of cultural significance, targeting the collective identity and cultural continuity of the Palestinian people. Mosques, churches, schools and cemeteries — core places of communal life — were destroyed or repurposed. The destruction of these 530 sites wasn’t merely collateral damage but a deliberate strategy to displace and disconnect Palestinians from their heritage.

Economic oppression

One devastating economic policy in the Ottoman Empire was the seizure of Armenian property. Through a legal measure known as the Abandoned Properties Law, the government appropriated homes, businesses and farmland that Armenians were forced to leave behind. These assets were redistributed to Turkish families or auctioned off, solidifying the economic marginalization of Armenians. Additionally, Armenian businesses were targeted for confiscation under various pretexts, especially during wartime when Armenians were accused of disloyalty. With the seizure and redistribution of Armenian-owned enterprises to Turkish citizens, the state effectively eliminated Armenians from economic spheres they had once dominated, from trade to skilled crafts (Balakian 2009).

Another burden imposed on the Armenians was the “Kishlak,” or winter-quartering obligation. This policy required Armenians and other non-Muslims to quarter Ottoman, mainly Kurdish, soldiers in their homes, imposing severe economic hardships on Armenian communities. Families carried the financial burden of housing and feeding soldiers, which often depleted their resources and disrupted their work and daily lives (Balakian 2009). This policy placed a particular strain on rural Armenian households, as it drained their agricultural resources and hindered their ability to sustain their farms.

Economic warfare also played a significant role in the Palestinian Nakba, contributing to the forced displacement and destabilization of Palestinian communities. A critical example was the enactment of the 1950 Absentee Property Law by Israel, which allowed for the confiscation of property from any Palestinian deemed an “absentee.” This law targeted the assets of Palestinians who were forcibly displaced in the Nakba, resulting in the mass seizure of Palestinian homes, agricultural lands, businesses and other properties. Entire neighborhoods and villages were taken over, and these properties were re-settled through state-sponsored settlement programs, permanently cutting off Palestinians from their primary sources of income and stability.

Another key policy that contributed to economic warfare was the Village Files project, which predated the 1948 Nakba. As part of this project, Zionist paramilitary organizations, notably the Haganah, conducted extensive surveys and spying missions to document the layout, economic assets and agricultural productivity of Palestinian villages. This information was later used strategically to target specific villages for depopulation, allowing for the systematic destruction of Palestinian livelihoods tied to the land (Pappe 2007). The loss of agricultural land and the restriction of access to economic resources left many Palestinians without the means to sustain themselves, deepening their displacement and economic marginalization.

Lessons for today

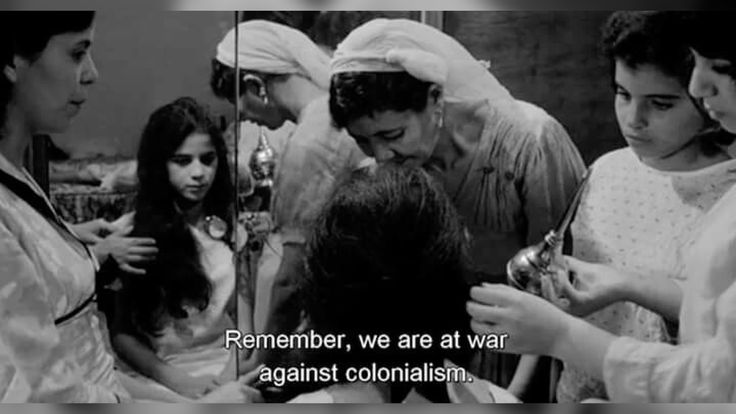

In drawing parallels between the Armenian Genocide and the Palestinian Nakba, we confront the disturbing continuity between genocidal tactics across different eras. These genocides aren’t events of the past — they are ongoing structures that persist today. The world saw another genocide of Armenians in Artsakh last year, perpetrated by Azerbaijan with the military support of Israel. Economic oppression was an integral component of this genocide, as the nine-month blockade of the Lachin Corridor set the stage for ethnic cleansing. Additionally, the ongoing genocide in Gaza is eerily similar to the Nakba in 1948. Both events involve systematic attacks on civilian infrastructure, from homes and schools to cultural and religious sites, intensifying Palestine’s long-standing anti-colonial resistance.

By understanding these parallels, we not only honor the shared struggle between Armenians and Palestinians, but also strengthen the call for justice, awareness and vigilance against continuous attempts to erase cultural identities and repeat history.

Be the first to comment