This article is the conclusion of her four-part series, exclusively for the Armenian Weekly, on the making of Encounters and Convergences: A Book of Ideas and Art by Seta B. Dadoyan.

Hard humanism ‒ After completing 10 drawings, I was tempted by the suggestions of animal and human forms in rock formations. The most primitive form of the head of a prehistoric being was symbolic of the soul of matter. It was a rock taking on a primeval life-force, a spirit and emotions [“Primeval”]. The concept took a spectacular expression and dramatization in the “Spirit of matter,” through a landscape of dry roots, branches, precipitating rocks and the emergence of a struggling horned creature on a hillside.

It is about how one becomes what one is out of sheer existence.

What I call hard humanism became manifest in the rock formation that evolved into “The thinker.” There is almost a complete head and eyes, squeezed between rocks but still focused and thinking, the most sublime of all human activities. I could think of no other means to describe the condition of someone in extreme encounters. It was being “human all too human.” This Nietzschean phrase is most expressive of human vulnerability and of the convergence of the act of thought and understanding, both in art and writing. It is about how one becomes what one is out of sheer existence. Beyond the various religious and cultural approaches to death and the dead, I see them as parts of the whole and always in the present time.

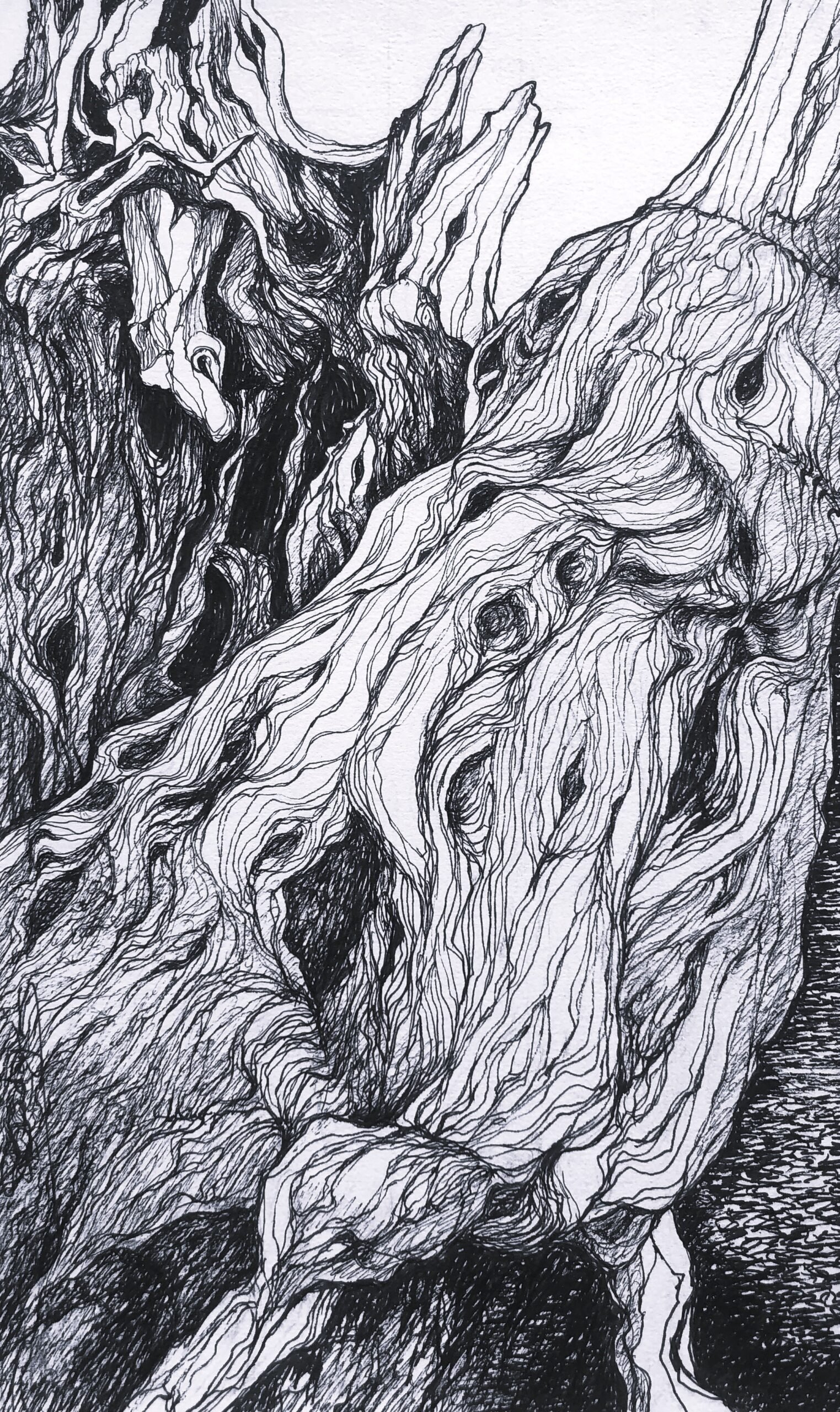

Of all the trees, I see the banyan tree as a tree with spirit, or the most expressive of the spirit of matter in perpetual motion. The unique forms and movements of the branches swirling, twisting, climbing and penetrating walls and pavements explore the endless potential of the life force. The banyan trees are also expressive of thought processes, events, experiences, encounters and convergences. As a student at American University of Beirut, and later a professor, I often sat by the banyan tree in front of the Assembly Hall with amazement, thinking of the many myths about it. Finally, in 1991 I made a drawing. While most of my memories of this institution and the people are mixed, the banyan tree stands as a “portrait” of a friendly place where I spent almost a quarter century [“Banyan tree of AUB ‒ A portrait”]. After over three decades I went back to the banyan tree and made seven more. Each drawing has its own story and world, and viewers will soon make theirs. The experience is as visual as it is intellectual and spiritual for both the maker and the viewer [illustrations #79 to #85].

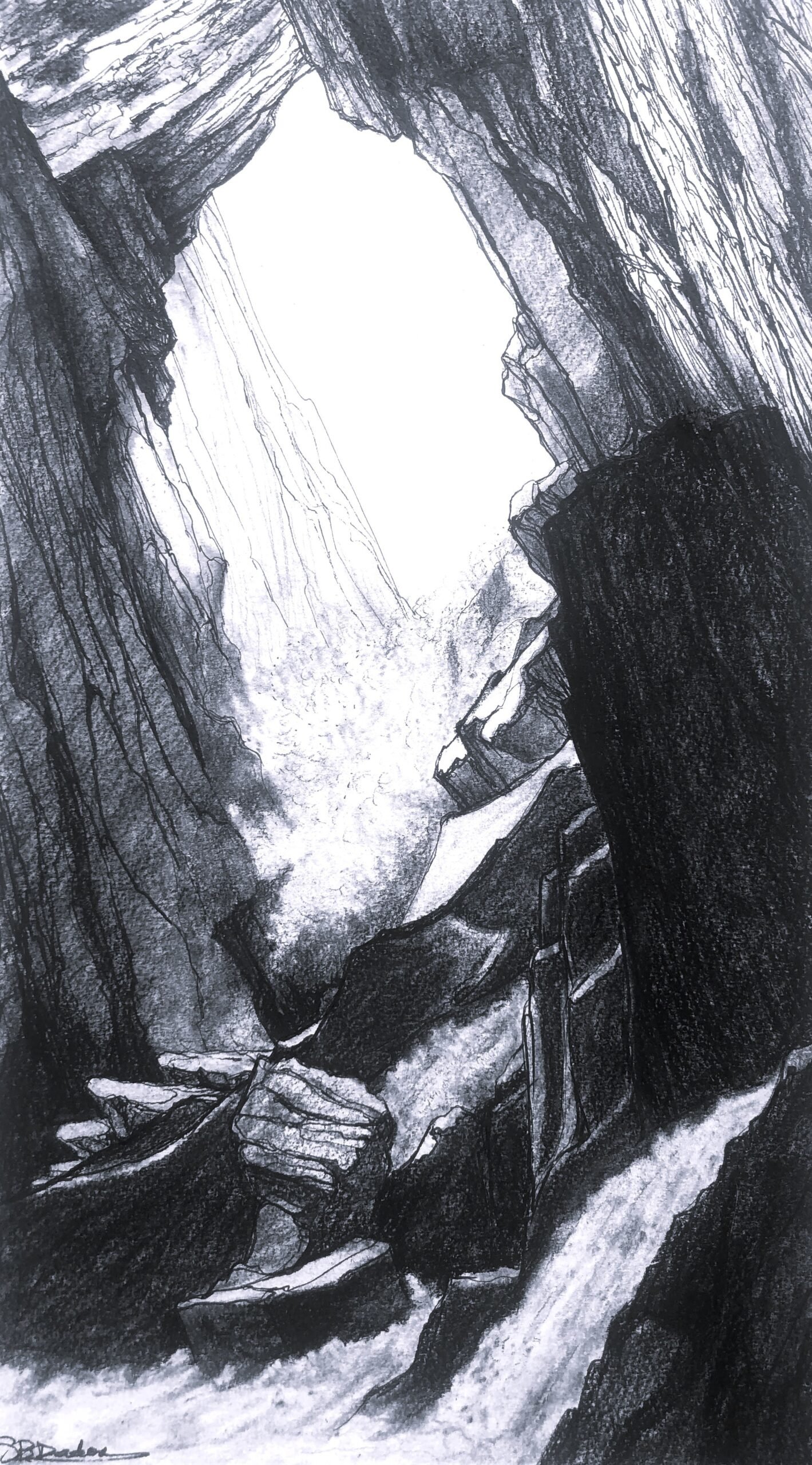

In my readings of the aesthetics of Heidegger and Gadamer, I was intrigued by the concepts of “concealment” and “unconcealment.” Both are about the truth-content of artwork. For Heidegger, artwork is the unfolding, the disclosure of a truth, or worlds of truth. For Gadamer, “Truth is an event or process in and through which both the things of the world and what is said about them come to be revealed,” and “converge,” in my term.

In “Concealment,” the dry roots and trunks “conceal” several crocodile-shape beasts of different sizes, with a central one in an upward diagonal thrust, frozen yet with open eyes as the soul of matter. The “Enterrement” (burial, #89) marks an extreme action of concealment. A conclusive work, of sorts, “The unconcealment” is inspired by a positive reversal. The view is from inside of a large cave, where water from a waterfall from a hill outside crashes in and turns into a calm river. On the lower right side, a dark rock-figure, with its back to the viewer, witnesses the “event.” The cave is a moment and a space of disclosure.

While I was preparing the cover design of my book, in the early morning of February 6, a massive 7.8 magnitude earthquake – probably one of the biggest ever in the region ‒ struck southeastern Turkey and northwestern Syria beyond the gulf of Alexandretta on the Mediterranean. Among many other cities, my father’s birthplace Ayntab/Gaziantep, very close to the epicenter, was mostly destroyed, my birthplace Aleppo was seriously damaged, and what was Armenian Cilicia, from where most survivors of the Genocide came, was devastated.

Homes turned into graves. Over four decades earlier, in 1982, the ‘Awkar building at Sana’eh, very near our home in Beirut, turned into rubble before our eyes by an Israeli vacuum bomb, as it was said, and became a grave for its inhabitants. Two years ago, on August 4, 2020, a near-nuclear explosion of a large amount of ammonium nitrate, unsafely and illegally stored at the Port of Beirut, exploded. Homes turned into graves, again. The motif of home/grave spontaneously inspired two sketches, “Resurrection,” perhaps of my “Thinker,” and “Homes and graves.” The episode also marked my return to the human figure.

In conclusion

The sequence of a dozen books over four decades and a selection of 90 artworks divided into two main phases, 1975-1991 and 2021-2022, reveal a pattern that sums up my scholarship and art of mind, spirit and vision. I have devoted more than twice as much time to my scholarship than to my art. Wartime Lebanon was a unique environment for encounters with chaos, strife and human suffering. My American-Armenian experience was another phase and produced its reflections. Both my scholarship and art were ways of encountering and converging in writing and drawing. If Wartime Lebanon triggered my art, my condition as an Armenian native of the Islamic World put me on a long and difficult path of research into unbroken grounds.

This pattern of unequal phases of writing and art is not common, because research is a most demanding dedication. The accumulation of over 50 wartime drawings in a relatively short time establishes the legitimacy of the two principles of my aesthetic and scholarship: encounters and convergences. Encounters led to the creation of contexts or “horizons” to understand and come to terms with my circumstances, through scholarship or art; convergences happened both in the artwork and scholarship. This is what I mean by my situatedness and the criteria for the truth-content of all my works, in writing and images. The objective of both activities was not capturing immutable truths or eternal beauties – there are no such things. All my works are statements that suggest deeper understandings for a more human and better world.

Finally, a cross-disciplinary look at my last drawings and my recent literature will immediately reveal their unity, even in style and the aesthetic of writing and drawing. The banyan trees penetrating the forest and breaking through brick walls, spiraling rock-bridges, steep stairs and rocks sprouting spirits are essentially images of confrontations and convergences, both in drawing and writing, about my experiences, and the historical experiences of an ancient and a small people in perpetual self-creation.

Bravo to Seta Dadoyan for her beautifully expressive ink drawings of Banyan trees. Apris!!