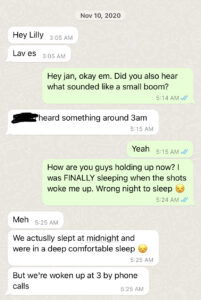

At 3 a.m. on November 10, 2020, I awoke to the sound of a pop.

Five minutes later, my friend who lived on the other side of Republic Avenue texted, “Hey Lilly, lav es?” (you okay?).

“Did you also hear what sounded like a small boom?” I asked. A gunshot, fireworks, a bomb. After 44 days of military planes flying overhead, we didn’t know what to expect.

In the morning, I learned that that was the moment when protestors stormed into government buildings, just blocks from my apartment.

The ceasefire was signed. The war was over. We were the losers.

Three days later, my friends and I ventured to the warzone. With a truck full of instruments (the musical kind), we intended to spend an afternoon singing in Dadivank, a 13th century monastery that would soon be ceded. What happened, instead, swerved us. A pop that lasted for three days.

The following is a collection of stories—reflections, memories, dreamscapes—of this journey from November 13-15, 2020—the immediate days following the 2020 Artsakh War.

***

Love stews in wartime. It cooks all that peace discards.

We’re on the cutting board. There’s no fruit—only rocks.

A friend picks up a helmet from the sidewalk.

“What rank do you think he was?” she asks, not lifting her gaze from the green shell.

A soldier without his helmet is a baby without a mother’s breast. We squeeze the skin and run our palms across smooth curves, but there’s no juice.

Her fruit had run dry.

In Karvachar, everyone is searching for their mother.

I wondered if the boy saw her when his head left his body.

I say nothing.

In Stepanakert, a soldier gives us his room, to sleep in his car. “I always end up there, anyway.”

At 10 p.m., he strolls in with a smile, carrying fresh matnakash – that finger-pulling bread – and a head of lamb. The smell made my stomach turn.

Haven’t we sacrificed enough?

A man stands inside what used to be his store.

“I burned it down,” he says, a stone marking the spot where a mother once held a face. “So that they wouldn’t have it.”

Later, when a woman’s hands strum a guitar and the milk pours out, his hands dig into the blade of a pocket knife, to cut the stream of tears.

His eyes are still burning.

Home exists in the sockets, which hold all they have ever seen—until the end. No timeline, no war zone.

Back to the cutting board, where a father buries hope in his hands, flanked by the sun.

The body is built on, above, under, inside war.

Time sneaks in and out of his walls.

How clever, Armenian is. պատերազմ | war.

Through him, a wall. (պատ | paat or baad)

War builds and tears—sifting sand and shifting tide because cliffs will not budge. Here, no one escapes the mountains. The soldier boys know this. I have read it in the tunnels of their eyes.

In a morgue, outside the hotel, a father scrolls through images of someone’s dead boy—but not his. “I don’t know which is worse—finding him here or never knowing.”

In Artsakh, our hands never skimp. We cup hope like balls of kufte—knuckles smashing against ribs, flicking water on lips—but her insides withered long ago. Only a green shell remains.

A seed is enough to hope, says peace.

What does she know? She’s never felt the tremors of a heart snap—or watched meat knead itself into a mountain.

Love in wartime is communion, not as play, but survival. Flesh and blood are not metaphor.

Love in wartime is driving off, to save the body, while dousing your soul in the flames.

Love in wartime is scoring bread into ashes, broken helmets, lost sons—because peace is greedy, and war wants love, too. At any cost.

Part I: Of orphaned flesh and land

Papik was a son of Sassoun who never saw Sassoun. The first generation after the Genocide.

What do you call the children of orphaned flesh and land? They’re not children. They’re a family in a child’s body.

His parents made him to prove they were still human. Papik was a mother, a father, a grandparent, a cousin, a sibling—a sapling placed in a child’s palm.

His mission—his calling, his destiny—was to bring that tree home, one day.

So, he became a carpenter. A carpenter with the cleanest hands.

***

The last time I saw Papik was on the night of the 12th. My uncle’s birthday.

In one room, cake, laughter, children blowing candles—

in the other, death slowly calling for an old man.

I made my way from one to the other—just 12 steps. I didn’t sleep that night.

A few hours later, I walked down the steps of my apartment. A lot more than 12.

Five young women on their way to a warzone.

Or what was left of it. I stopped counting the Russian tanks moving by us. The potholes my friend declared war on.

A young soldier on the phone with his mother, saying, “Don’t worry. I burned down our house.”

Civilians drilling holes in the walls of a 13th century monastery. Ripping out khachkars like babies under rubble.

Swerving to avoid falling in.

The ways we propel ourselves to safety. The contradictions suspended in this space, between life and death.

After hours of dutiful battle, our car gave up—and nestled in the pit. A tonir of bodies, calling for mercy. ողորմություն. vo-ghor-mu-tyun. A big word.

Տէր Ողորմեա՛ Տէր Ողորմեա՛ Տէր Ողորմեա՛

Lord have mercy—my favorite hymn of our Badarak, sung before confession.

Where we ask for healing for the sick and rest for the dead.

We came to say goodbye. To what or whom, I’m not sure. To land? To ghosts? To time?

We’ve been singing—praying—for mercy all our lives. Stewards of the tree with no home. Where death craves dignity and life craves light.

Karvachar—“a place for selling rocks.” In two days, this land would be ceded.

But today, we plant one final seed.

An Armenian soldier tends to our tires. Then, another joins. Soon, there is a man for every woman.

My friends empty the trunk and assemble their instruments. A small serenade to soothe the spirits.

I look around. Smoke, cranes, craned necks.

One man, hunched in the corner, pulls out his pocket knife. It digs into his palm. He doesn’t blink.

Before we leave, he picks up a rock and stands on a pile of ruins. “This was my store. I blew it up.”

No one says that war turns fields into mines.

He throws the stone back onto the ground.

Let the canaries deal with it.

Part II: We die with blades fashioned from our bodies

I wanted to see the once-store owner smile. To re-member the lines on his face he’d rather delete.

A book I could not read.

But when I snapped the photo, I saw (Kevork) Chavush. The man we all know from that one image. The fedayee my grandmother maintained was our ancestor. Her great-uncle.

When Chavush was wounded in battle, his comrades left his body under a bridge.

The next morning, a Kurdish chieftain found him. The last word to leave his lips was “water.”

I wonder if he said it in Turkish. What frees the tongue decomposes in the earth.

Armenia, land of stone, dust, tuff—pink and chalky, like our meat.

And our bones.

We die with blades fashioned from our bodies.

Chavush’s tongue, the store owner’s palm, Papik’s mustache.

We sharpen the grounds as the borders collapse around us.

In 2017, I stood where Chavush died—of pistol and thirst, eight years before the Genocide.

And where two thousand years before him, our gods would revel with us mere mortals.

The store owner knew his place in the timeline.

Ժամ (zham | time) is a Parthian word—an Iranian language that has survived more in Armenian than in today’s Farsi.

ժամ is a fossil, fueling our tongues.

ժամ has a different worth for those living in history.

What happens when the sun hits the page?

It molds. բորբոս (borbos)—origin, uncertain.

As we drive away, our ears fill with dust.

We’ve lost balance.

Part III: May this grief pass over you

I imagined the once-store owner’s hands, striking a match. His blown-up shell. Whirling feet smashing broken pieces. They would not reap a fallen harvest.

As we pulled into the complex, my eyes darted to the mass outside. Lined up, like a tour at Buckingham Palace.

We’re not known for queuing, but one too many blows create patterns. Sparked into order. A grove of trees, ready to embark on safe shores.

They’ve commanded our hens, laying eggs in their prisons. The babes are now grown. Gawking at our swollen tongues, lunging for seeds in the soil.

Inside, I clasp my fist. They’re drilling the walls—ripping out cross stones. Soon, those orphans will alight in a Yerevan museum. Another piece, ripped from the seams, to thrust into a drawer.

We’re good at “preserving” our skin.

In French, grenade means both weapon and pomegranate. The bomb is fashioned off the fruit.

Chicks throw the noor against a wall. Smash it clean. Count the seeds, splattered on the ground.

Let the air hit our swollen bellies. Fortune, they say. You will bear many children.

Papik was born in the final days of the Genocide. His mother’s dying act.

His grandmother hid the boy under her dress as they escaped to Aleppo. “Don’t make a sound,” she commanded.

This is the story that my family etched into our fruit—the one that would reach my ears, as I reached for a bite.

I was 17 when that miracle baby died. I never heard him utter more than a few lines.

Papik’s stepmother Arusik was a vindictive woman, says Tatik. “I was pregnant, and she left me out in the cold for hours—until my husband came home.”

That son in her belly died soon after alighting on soil.

Tatik named her third son after him, Hovhannes (John).

My dad, the middle son, asked why he was not given his dead brother’s name.

Tatik’s eyes shifted from the window to the chalky walls, as if to say, “This grief will skip a generation, so help me God.” She named him Matevos (Matthew), the first apostle to follow Jesus’ light.

That was the story she carved into our tree.

Then, her eyes said this: If I flip a coin, it’s not hate on the other side—it’s grief. Always grief.

Love, grief, grief, love.

There is no room for hate in the refugee’s pouch.

I look back at the man with the drill.

“May this grief pass over you,” he says, as the hands dig into Mother Mary’s ribs.

Part IV: He always calls

The second week of the war, a teen described to me the onset of the storm. “At the sound of the bombs, Mother bolted and broke her leg.”

All night, she bore the pain, in that basement bunker, as men dropped explosives into their neighbors’ homes.

In Stepanakert, shattered glass and perforated walls huddle faintly against abandoned puddles. Reminders of tempest, halted just two nights ago.

I count the storefronts with their limbs intact.

That night, I wrote a poem about the sapphire shards lining the pavement of a once-hotel. The silence after the shriek.

A white sheet blows in the breeze. Mother’s love is a clean bed in a dirty world.

Maneuvering through the lobby of “Armenia” Hotel, we soon realized that there was no staff, no food, and no clean beds in sight. Only men.

In the center table, journalists clamored in French, Polish, English—showing off drone footage of freshly occupied Shushi.

“We wanted to see the gorge where the action happened,” says the Italian.

action (noun): hundreds of bodies, piled atop one another in ‘no man’s land.’ Waiting for Putin’s thumb to send in ‘rescuers.’

“The Azeris kept shooting at us—despite our obvious PRESS jackets!” The tone was incredulous. His colleagues never lifted their eyes off the screen.

Mine darted to the back of the room, shrouded in smoke. Fathers of missing soldiers—some in uniform, having served in the First Artsakh War three decades ago.

Their once-victory, now, a white sheet, blowing in the distance. Silence that drowned out drones.

A thin line between fathers and foreigners, encroaching on Armenian territory. Drooling for the scoop.

Many of those reporters are now in Ukraine. Their eyes never shift from the lens.

From the battlefield to the mortuary—just three footsteps.

One father crouches on the corner of a sofa. His face, a shade of cherry. He hasn’t slept in three days, he says.

When the war ended, he drove straight here. To find out what became of his son, a 19-year-old conscript.

In the car, he tells us that he offered to pay a bribe, but his son refused. “It’s my duty to serve, Pap jan,” the boy insisted. He began his service in the summer of 2020.

“My son is very generous. Always lends his phone to friends to call home,” the father beams, sinking into his seat.

The civilian hospital was barricaded during the war, says the guard at the gate. So, we navigate to the military one.

Clouds drop to our level, heavy fog blocking the city view.

“This feels like a film noir,” I whisper to my friend. Her smile sifts through glass. Sand in a broken metronome.

Men whirl across the lobby. As chaotic as our hotel.

As we enter the exam room, the father turns to me and says, “I’m waiting for his call. He always calls.”

Part V: We don’t do grief

“You know how many of these we’ve seen?” the doctor muttered, rolling up his sleeves. The middle buttons were missing.

It was my first time in a military hospital. In the U.S., VA facilities are notorious for abusive practices and subpar care.

I wondered what the state of an Armenian facility during wartime must be like. It didn’t take long to find out.

“Just get him back and make sure he sleeps.” As the medic turned away, the green faded from his uniform. Like someone wrung out the water from his face.

I don’t recall the ride back. Only that, once we arrived, the father sat back on the same couch, in the same position.

At 2 a.m., my friends ran over. “We’ve found a room!”

They had wandered around Stepanakert, stumbling into hotels, trying to find a place to spend the night.

With no staff, they resorted to opening random doors. One was the room of the EVN Report crew, who had been camping there since the war began. A member of their team showed us the linen closet.

We eventually found a place. Recently abandoned. The pillows smelled musky. When I opened the closet, there was a military uniform.

“He’s not coming back,” said one of the girls, ripping off the soiled sheet of the mystery soldier.

Love is a clean bed in a dirty world. White fabric, sprawled on a lonely mattress.

24 hours before, I watched my uncle’s grandchildren blow out his birthday cake, steps from my grandpa’s deathbed.

A son buries his father. That’s the order.

But war doesn’t care—he blows it all up, leaving us to rearrange the pieces.

Time’s line drifts closer and closer.

The cherry face on the couch, the phone that won’t ring, the suit unclaimed.

A father burying his son, without body, without soil.

I didn’t sleep that night, either.

My friend and I returned to the other hotel. To find the father where we left him.

“He’s alive—I can feel it. I can’t explain it—but I just know it,” he says, as the journalists clear out, back to Yerevan.

“The Karvachar road is supposed to be handed over [to the Russian peacekeepers] today. We don’t want to risk getting stranded here,” the Italian tells me. The chatty man of the bunch.

What he really meant to say was, “There’s nothing left for us to see here. We don’t do grief.”

Another father informed us that the handover would be delayed by ten days.

Later that morning, he would have a private meeting with the President of Artsakh, to discuss the issue of POWs.

He asked us—four young (female) musicians + me—to stay. For emotional support.

The eyes on the couch, now as red-streaked as they were white, blinked softly.

We huddled around the fathers, asking for the names of their sons, their ages, when and where they were last seen.

A guitarist’s hands, now strummed the notes belted by the choir. Line by line, they cleaned up the mess of men with their guns and bombs and drones.

That white sheet was soon brought into Parliament, in what became the first of many meetings on the status of missing soldiers.

In the two and a half years since, hundreds of service ‘men’—boys no older than 20/21 at time of capture—are still languishing in Aliyev’s prisons.

As the journalists left the city, the fathers migrated across the street. “Action” means something different to those carrying sheets that bleed in black.

I wonder how many of them are still holding on to the uniform in the closet.

Part VI: Hope is a four-letter word

Everyone who risked staying the extra night gathered at the steps of the Parliament building.

Fathers congregated as their “leader” walked inside with the sheet of names. Momentarily brought back from purgatory.

“This not knowing is the truest torture,” said one of the fathers, the night before.

“No, it’s a hidden blessing. Hope as an ember,” said another.

Every night, a fresh batch of photos would arrive at the local morgue. The fathers would take turns going, sitting, watching. Image after image. Hoping and not hoping to see their son.

Hope. հույս. (huys) A four-letter word in both English and Armenian.

“It is impossible. Over 80% of them are deformed—missing heads, missing limbs. Unrecognizable.”

“Barely human,” said another.

Later, my friend told me that one of the fathers had asked us to accompany him. She refused.

“We will be here when you return—to provide whatever you need. But not that.”

For a young woman to be in this space, among grieving Armenian men, is high intimacy. But we also had to honor our boundaries.

Outside, I wandered between the groups, stopping to answer questions. Usually, about why I’m here, as an “American.”

One father told me to stop smiling—that there is nothing to be happy about.

A soldier approached, offering to show my friend and I where he was stationed during the fighting.

As we walked up the mountains, he ran, he crouched, he pointed, “I shot them from here,” “my friend got injured here,” and he continued like this. His energy building.

When we returned to the hotel, my friend revealed that she had audio recorded the whole thing.

I was furious at the breach of trust.

But not only. The father’s voice kept ringing, “Don’t smile.” I was ready to claw at the concrete.

Meanwhile, our other friends had gone down to the shops, and somehow, found coffee and soap.

Love is a clean bed in a dirty world.

For the next five hours, we channeled our anger in the way of our mothers.

By cleaning up men’s messes.

The sink of the lobby bar was in a locked cupboard, so we washed dishes in the vacant ladies bathroom—in our winter coats, with cold water.

The men’s room was next door.

As the fathers walked by, I smiled.

Part VII: A sticky waterfall on the tongue

Three days and the clouds didn’t part once.

Our ancestors believed that chaos was the boundary between heaven and earth.

That beyond the horizon, bodies rise like curtains, to reveal the sun.

Inside, we rise and rivet in rhythm.

One makes coffee while another brews tea, as the third picks up dishes for the fourth to wash.

The fifth glides from table to table, chatting with the fathers.

Word travels about an all-girls assembly line.

Customers queue up for Caffeine & Co.

A man approaches in combat uniform.

On the first night, he told us to stop singing.

“Sourj—black,” he grunts at the bread holder.

When we arrived at the hotel, it was barren.

He lifts the handle to find a warm loaf of matnakash.

“Akh, the presence of a woman!” the father beams. Sourced by sorceresses, another might have said.

Inside the ladies’ bathroom, hands turn the hue of the cherry-faced father. As I wash, he tells me stories of his son.

Later, while loading dirty cups onto a tray, he runs over.

“We just got a call from my son’s number! They didn’t speak Armenian, but they found his phone—he must be alive.”

“Lil, this is the best news,” he whispers, as we hug, for the first time.

That evening, his nephew arrived from their village.

Soap, water, rinse, dry. Reload.

I pick up the dishes and head to my station.

Order. We’re all looking for something to grasp.

Eyes shift, hands never leaving their pockets.

The boy didn’t seem to share his uncle’s enthusiasm.

On we went, like this, until nightfall. The hotel we stayed at the first night had lost electricity, and this one was full.

A soldier offers us his room. “I sleep in my car, anyway.”

Earlier, one of my friends picked up a soldier’s helmet off the pavement.

We take turns wearing it, imagining which position and rank the boy would have had.

Which position and rank we would have had.

At 10 p.m., the soldier strolls in with a friend, carrying a tray of lamb and bread. No one touches it.

Downstairs, the fathers are ready. My friends play, they sing, they laugh.

A body in fatigues plops down beside me. It spurts.

Broken engagement. Move back from Russia. Desire to live in the homeland—no matter who’s running it.

All three, just ten days before the war began.

“So, what’s your deal?” the soldier winks, between puffs of his cigarette. The lobby was now a smoke screen.

No matter how hard we tried to clean the soot off the clouds, the cups, the chords—men prefer a modesty patch.

The sun, shrouded in fumes.

After we left, the lobby decayed—we were told. No one thought to wash a dish for himself.

But for now, the “don’t sing” father belts out a revolutionary tune. It builds, as the smoke dances with my lungs.

“Are you single?” More puffs, penetrating eyes, nostrils, cracked lips. Hee hoo hee hoo.

Could no one else feel the flames?

“Here’s something sweet for you,” an arm reaches out as legs jump from their seat.

Hee hoo heeeeeeead leans against a car tire.

Buried inside a starless sky.

A sticky waterfall on the tongue.

Snickers was a lover’s mark during the war. Women would attach notes to the candy bars—sent to their beloveds on the front lines.

A clear stream tickles the throat. Wheezing ash into phlegm.

I eject the inhaler and walk upstairs, leaving the soldier’s gift on the table.

Part VIII: A death [of] order

The music stops, and soon, my friends join me in the room.

The fathers’ energy has lifted their spirits, momentarily, by a string and a piece of glass.

“We’re going out—are you coming?”

“No, you gals have fun. I’m calling it a night.”

“Did you hear about Nshan?” trails another voice.

Cinderella after the ball. Her carriage back to a pumpkin. Shards glint in silence.

Nshan, the cherry-faced father, whose relatives were now camped out at the lobby.

Earlier, he was describing his գյուղ | gyugh (village) to me.

“We have lots of fruit trees—apricots, apples, cherries. Please come with your friends. Stay overnight. My son will show you around.”

What a strange rooting, I thought. The cherry tree man with the cherry red face.

“They identified his son’s body today,” said the voice. “Everyone knows but Nshan.”

As my friends leave, I try to sleep, but can’t stop sputtering. Exhaust emissions, warming the mattress.

There is no word for a parent who has lost a child.

In the U.S., one professor has proposed “Vilomah”—a Sanskrit word, meaning “against the natural order.”

mah (մահ) means “death” in Armenian. Vilomah. A death of order.

A dirty cup, a shattered glass, a body lying in a gorge.

Hope is an ember, said one father.

Hope is order, another might say.

Hope keeps the string tethered. The glass intact. The cup pristine.

In the morning, I search for the man who clings to that four-letter word. And I fail.

Back to Yerevan.

We began this journey in Dadivank, to bid farewell to a place we never knew and now never will.

But this story was never going to be linear. Not in a land with broken lines.

Five young women over three sleepless nights in two abandoned hotels. In the center. Men on edge. Uprooted branches. Fallen borders. Fallen boys. Falling fathers.

As we leave the city, we say goodbye to the sons we never met and now never will.

A few minutes go by, and a white car chases us down. We pull over.

He gets out and walks towards us.

On the side of the road, we take turns hugging—in silence.

Then, he wipes that fruit-laden face, now ready to burst—and gets back in his car.

We watch him drive away, shrinking in the distance.

A white sheet blowing in the breeze.

Be the first to comment