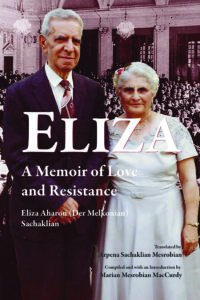

Eliza: A Memoir of Love and Resistance

Eliza: A Memoir of Love and Resistance

By Eliza Aharon Sachaklian

Gomidas Institute Books, 2021

210 pp.

Paperback, $23.50

As the saying goes—they don’t make them like that any more. This memoir of Eliza Aharon Sachaklian, devoted wife, mother and grandmother, is important on many levels. Eliza is a quietly determined figure who does not lose sight of her origins. She records calmly (and often without self-pity where others would have railed and wept), the stoical life of an Armenian woman—from girlhood in ‘Armenian Turkey’ to old age in America—at a time of great turmoil for the Armenian nation, and indeed the whole world, during the first half of the twentieth century.

She gives an often humorous account of small town Armenian life in Turkey in the early 1900s—details of traditions and cures which are becoming more and more remote and some which are already forgotten. All of this is told in the particular idiom of Aintab, faithfully translated without loss of flavor by her loving daughter Arpena. Those with Aintabtsi ancestors will smile as they recognize particular turns of phrase which others may find hard to interpret, and perhaps non-Armenian speakers will find it difficult to understand the full meaning of some of them. Men and women with extraordinary names make appearances: Khatchadour Bonapartian, a young Tashnag doctor (later an important Armenian Revolutionary Federation [ARF] official); Kuchuk Sarkissian Khatun Baji, Little Sister Sarkissian Khatun; Alte Parmag Zakar, Six Fingers Zakar.

Eliza was born in Aintab, where she grew up in its surrounding villages and later in Dortyol, in eastern Cilicia. Her family were good people with many clergymen among them. Her father became a kahana (married priest) at the behest of the archbishop of the area who needed someone educated to take care of some villages. Der Avedis took his task seriously and went off to minister to his flock, leaving behind his wife and young children who would later join him on his peripatetic existence—eventually settling in Dortyol.

Her description of the people of Missis, who scandalized the whole family with their crude, or rather vulgar, language is priceless. So bad was their language that the young Eliza was not allowed to associate with the village children, and only after Der Avedis’ patient coaching, did the people speak in a less shocking way. A rather sinister charlatan of a sheikh makes an appearance too, a sort of cut-price Gurdjieff, who turns out to be a Moslem Armenian. There are many suitors, some better behaved than others.

Eliza laments throughout her memoirs that she had not received a good education due to the lack of girls’ schools in the region. She had to make do with eavesdropping on the boys’ lessons at their schools. However she does go to an American mission school somewhere near Adana, and boards there for two years. She gives a vivid account of the small town Protestant school, where, “The second year my knowledge remained essentially at the same level [as the first].”

The bright young girl was encouraged by her parents, and her father in particular, to be independent minded and not to adhere to some of the more ‘backward’ traditions in their society, including the arranged marriage of very young girls. So, she writes proudly, she chose her husband herself; a young Armenian man named Aharon Sachaklian recently returned from America and proposed to her after having seen her only once. (Much later, when she visits some relatives in Beirut, she is shocked to see that they still expect the brides in the household to keep silent before their in-laws and the menfolk especially—a barbaric tradition which demanded the silence of young women.)

Eliza provides interesting details of the engagement and vows which follow. However, on his first proposal young Aharon kisses her in public, much to everyone’s consternation. Other than that, he is a thoroughly decent Armenian man. Some months after their marriage, they embark on their long and arduous journey to America, taking with them a nine-year-old relation of Aharon’s brother called Asadour. Poor Asadour turns out to have the dreaded eye infection (trachoma) and is denied a visa to America. The dilemma of what to do with the young boy and the time taken to get replies to their letters to America are dealt with in a few nail-bitingly tense paragraphs. That passage aptly illustrates the bravery of Armenians who set off on long journeys in those days—the adverse occurrences they had to deal with and the time it took to make a journey. (Even the relatively short distance between Dortyol and Aintab—some 116 miles—took several days as there was no direct route.)

Once in America, the young couple settle with Aharon’s older brother Stephen, who turns out to be rather demanding and not to Eliza’s liking. “This was a new life for us, especially for me … No language. The freedom I had in Dortyol was entirely gone.” She endured some time in the unhappy household.

Aharon was an accountant by training; he went to Boston where he got the job of installing an accounting system at the Hairenik and served as manager. Eliza follows him, and although free, the paragraphs describing her lonely life as the wife of a driven and conscientious man make sad reading. Eliza’s family had strong affiliations with the ARF, and indeed that is how she met Aharon (he had even been involved in a bit of gun-running when he visited Dortyol). He now became thoroughly involved in the relief efforts for Armenians, and after WWI, Aharon was present at the ARF convention in Paris. (Years after his death, Aharon’s family found out that he had been the finance and logistics officer for Operation Nemesis, a secret campaign to assassinate the Turkish leaders responsible for the Armenian Genocide of 1915 and who had escaped legal punishment.)

Thus, Eliza becomes acquainted with the leaders of the ARF and indeed entertains many of them at her home. The Armenian cause was ever-present in her life. Many of the First Republic’s high ranking officials are mentioned as friends in the memoir—General Antranig, Dro, Armen Garo and so on. Years later during her visit to Cairo, her daughter Arpena is treated for a fever by none other than Dr. Hamo Ohanjanian, the third prime minister of the First Republic of Armenia.

All this is told with a wry sense of humor. She comments on a Kurdish man who was not at home: “Who knows, he may have gone on a robbing or raiding expedition.” Years later, she visits an ex-beau of hers out of curiosity to see if she had missed out by not marrying him, and, thanking her lucky stars, she compares him to her husband: “Aharon Sachakliane oor, Minas Kassarjiane oor!” Or indeed her political aperçus on the occasion of the declaration of independence of Armenia in 1918: “What happiness and joy for the freedom-loving people, except for the Ramgavars.” And again, after the demise of the Republic: “The country fell into the hands of the Communists. The Ramgavars drew a deep breath.”

Did Eliza love her husband? In time, yes. She certainly never refers to him in any tone other than respect and pride. She was probably pleased to have left Turkey when she did, even enduring years of loneliness and garod for her mother and brothers. When writing her memoirs, after the death of Aharon, she signs herself in widowhood as Eliza Aharon Sachaklian, taking his first name as her middle name in the Armenian way. Through the memoirs, she refers to him as Aharon, then Aaron, then Hayrig (father), and sometimes as Sachak. Did she know of his involvement with Operation Nemesis? I would say yes, because when she writes about him, it is as if she is extolling his virtues but holding back. If she were speaking out loud about him, it would be in hushed tones.

Eliza’s granddaughter Marian Mesrobian MacCurdy provides a sweet and loving introduction to the memoirs of her beloved grandmother. She gives much-needed explanation of Eliza’s family history and tells the story of Eliza’s brother Mihran, who was killed during the Battle of Aintab in 1922. She explains in detail the immigration quotas to the United States in the years before WWI. There are good sections on Armenian history of the time, and the nascent ARF, as well as more information about her grandfather’s—not inconsiderable—involvement in it.

Excellent book report. Thank you Rubina. Can’t wait to read your upcoming book, The Long Shadow.

Hi Rubina, My name is Souren Sevadjian, and I wanted to share with you about my great great grandfather Bedros A. Sevadjian. My father Avedis and my grandfather Souren, told me the story on how in Africa Ethiopia he escaped with gold and jewelry around his waste belt. But if you know about him please let me know. You may contact me via cellphone at 7472424475 or email at CarLionMotorsportInc@gmail.com Thank you