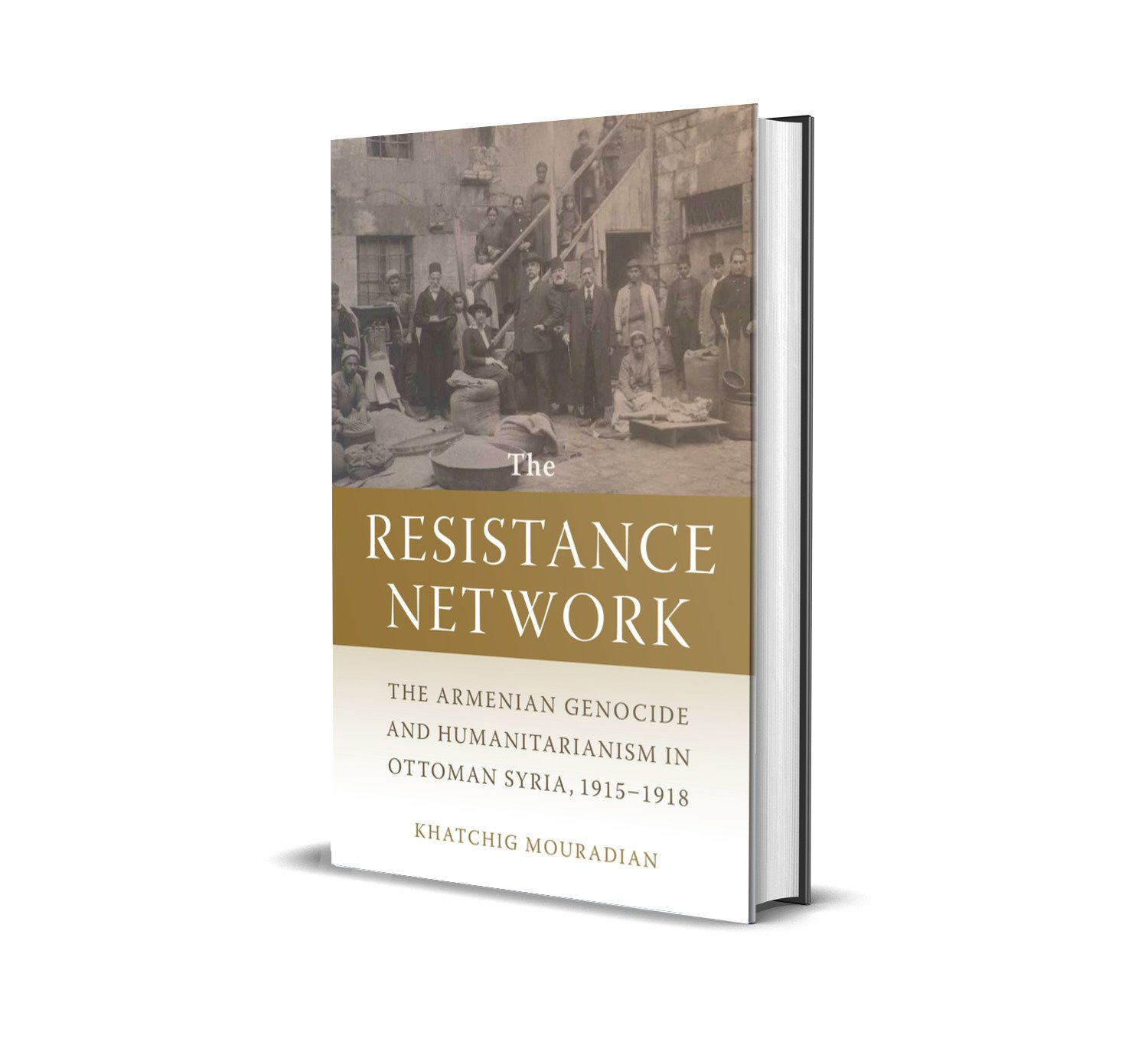

I reread “The Resistance Network” by my dear friend Khatchig Mouradian as soon as the book arrived from Amazon. Luckily, I preordered it. As of this writing, it is still “temporarily out of stock.” Why? Because it is THAT good. It is necessary reading even more so now than ever before. This is not another book on the Armenian Genocide. This labor of love that I was fortunate enough to witness the creation of throughout the years of our friendship and travels to Western Armenia and beyond is a touchstone not only for Genocide studies, but also should be recommended reading in the Inspirational genre.

I reread “The Resistance Network” by my dear friend Khatchig Mouradian as soon as the book arrived from Amazon. Luckily, I preordered it. As of this writing, it is still “temporarily out of stock.” Why? Because it is THAT good. It is necessary reading even more so now than ever before. This is not another book on the Armenian Genocide. This labor of love that I was fortunate enough to witness the creation of throughout the years of our friendship and travels to Western Armenia and beyond is a touchstone not only for Genocide studies, but also should be recommended reading in the Inspirational genre.

In what is probably the darkest and saddest winter in Los Angeles as the novel coronavirus rages like a tsunami across the Southland, the nation and the world, Khatchig’s book is an incredibly timely and necessary reminder of the most basic, perennial and unbreakable capacity of human beings – when pushed through the worst stages of hell, inferno and purgatory – to find among such atrocity and horror the will to resist in the face of the inevitable trauma and loss borne of man’s heinous inhumanity to man.

As we all do our best within our toolboxes to endure, survive and bid farewell to loved ones we lost in this brave new glowing world of social media in the era of the pandemic, “The Resistance Network” is a paean and a fully committed act of scholarship seeded in the human wherewithal for resistance in the face of the inevitable horrors perpetrated by the Ottoman Empire against the Armenians. In rereading the book, I found myself constantly nodding or looking up for a few minutes as the tales of these unsung heroes and lost souls braided together in the tapestry of the layered and focused narratives. After finishing the last pages and looking back on the stacks of legacies and tales encapsulated in the beautiful binding, the book is a testament to what the power of scholarship can do when it is ingrained with clear and precise prose. The book has that rare capacity to trigger multitudes of little bright epiphanies within the darkness of the era inside the mind’s eye of the reader.

There is no shortage of horror and pain that the Armenian people have tragically endured again in the wake of the heinous and cowardly war started by Azerbaijan and Turkey on September 27, 2020. Yet again, the Armenian nation was outnumbered fighting two Goliaths and the silence of the international community. And yet again, the past came to sadly remind us that above all, resistance and endurance remain intrinsic to the essence of what it means to be an Armenian.

I have never thought of any book on the history of the Armenian Genocide as inspiring. All of them have been illuminating and sobering to the core…except this one. Khatchig, in his passionate and clear-eyed commitment to his decades long study and heavy lifting, has taken the blue flame of the pain of the Genocide and churned it into an offering of hope and a sincere reminder to all who resist today and who will no doubt resist tomorrow. We need this book for our souls now more than ever. I hope that Khatchig’s scholarly torch will illuminate and inspire you when you read this masterful book.

Looking forward to reading this book!

This book fills a big gap in our knowledge and understanding of the Genocide. Congratulations, Khatchig, on your important contribution to the scholarship on this subject.

For primary source documentation, also read, “Resistance: a Diary of the Armenian Genocide 1915-1922,” by Misak Seferian, published 2015. This is a seven- year, daily diary, by a resistance fighter, that was written while events were unfolding before him, and as he participated in them. Misak Seferian’s diary-keeping began in 1915 when he saw his village invaded and his grandfather murdered. It is a firsthand documentation of Armenian resistance, from 1915, right up to the beginning of the Russian Revolution and Misak’s escape from a Bolshevik prison with the help of the underground resistance movement. Their methods are carefully noted.

There are many accounts of individuals who risked their own lives in order to save villagers. There is a very touching account of Armenian soldiers taking great personal risk in order to save terrified orphans hiding under a bed in a house. There is an Index listing hundreds of villages, and names of individuals, and several caravan routes. There is almost daily weather, the names of several murderers, the locations of many bodies, and the names of many who disregarded their own lives in an attempt to save villagers.

Misak’s notebook entries became hundreds of articles published in serial form in the Hairenik in the early 1930s and 1940s. This book is a 350 page translated and edited version of those articles. The front cover is a photo of Misak Seferian and Antranig. It was taken in a tent during the battle for Erzeroum. Many lives were risked by the resistance movement in an effort to save the Armenians in Erzeroum.

The back cover has Chris Hedges’ thoughts about resistance.

It’s available at NAASR in Boston, or The Armenian Relief Society in Toronto.

Here is an excerpt from May 1918.

“Enemy artillery shelled us the entire night of May 21, 1918. Both of

our regiments remained at their positions the entire night without rest,

becoming very fatigued and less able to resist. At dawn on May 22, the

Turks doubled their artillery and attacked us. After a furious battle of

three or four hours, their much larger forces invaded the heights on our

left wing. Both of our regiments retreated to the north after losing many

martyrs. Hamamlou Station was invaded later the same day. That night, all

of our forces retreated to a point very close to Gharakilisa and formed a

new front. Several battalions from Gharakilisa joined us. They told us that

the entire population had vowed in one voice, “Either liberty or death.”

“Boys,” said Ardoush, one of the new arrivals, “tomorrow morning,

these fields and mountains will be filled with Armenian soldiers. Fifteen

to sixty-year-olds will come, and together, we will defend our fatherland

against the Turk.”

I was so happy that I did not know what to do with myself. I ran from

position to position, repeating the joyous news coming from Gharakilisa.

That night more than one thousand youths arrived from Gharakilisa.”

“We have to read the books that ask more of us than we are willing to give,” said Franz Kafka, the remarkable Czech-German writer who lived around a century ago.

Armenian Genocide-themed literature cannot avoid confronting readers with these profound and uncomfortable truths. I look forward to finding this work and reading it closely.

My soon-to-be-released, self-published novel ‘Angel of Aleppo, a Story of the Armenian Genocide’ is researched from primary documents that detail horrific images, narrative sequences highlighting the cruelty visited on Armenians by the Ottoman Ittihadists and their successors. And there are references to persecution and discrimination elsewhere in the world, which highlight to us that inhumanities exist and literature – by its unique connection between each individual reader and the text – can demand more than the reader might normally give, and in doing so, can draw attention to truths swept under history’s carpet by hands that are all-too-often stained with the blood of their victims.

The more we can present literature on the Genocide to the wider world, the more we can advance justice for the Armenian people

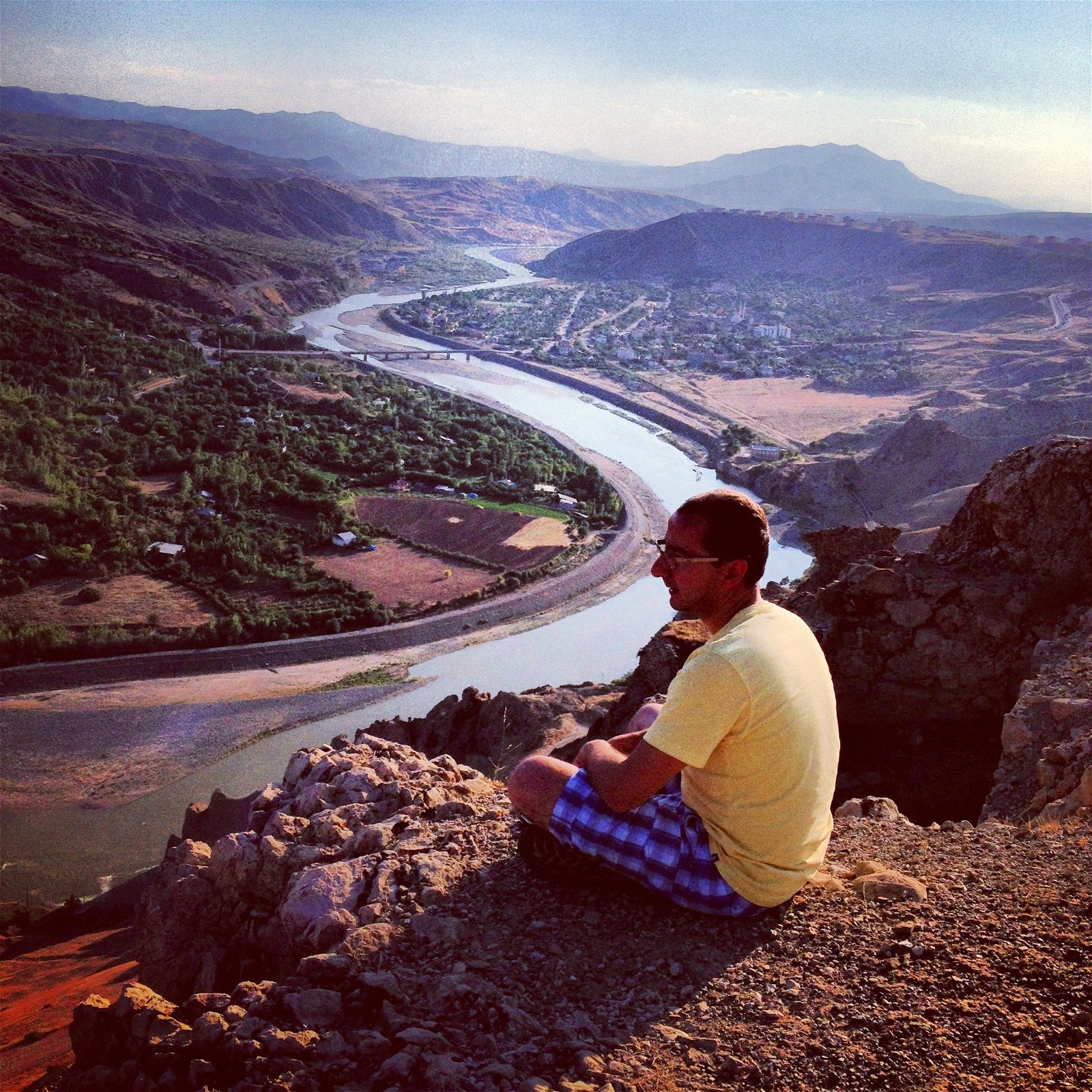

The photograph above of Khatchig in Palou looks so peaceful, but I know it is not. Armen Aroyan took me on one of his tours to the very front of that bridge in the photo. Police cars had been following us for some time. They would not allow us to cross the bridge.

My father, Misak Seferian, escaped from the caravan at Palou. He was captured and made servant to the Chief of Police in Palou for almost two years. His name was changed to Muhammed by the police chief. One of his jobs was to collect money from the prisoners in the jail and go to market to buy them food and water. The men in that jail were from Palou and the surrounding area. Here is an excerpt from my book “Resistance: a Diary of the Armenian Genocide 1915-1922,” about that bridge and that river that Khatchig is looking at.

“Olan, Muhammed, make sure that the Armenians don’t spend all

their money. When I break their heads open, something should remain for

me to take in exchange for all my work,” laughed gendarme Ghasab Yasim,

who had killed thousands of Armenians on the bridge at Palou and then

thrown their bodies into the river.”

I remember that Jamal, our Kurdish bus driver, threw rose petals in the river, while we all stood on the river bank and said silent prayers for the bodies in that river that now looks so peaceful.

The prisoners were all murdered. Their bodies were left in the field behind the government buildings of Palou. My father documented the name of the Chief of Police who ordered their killing, and the name of the man who carried out his directions. Another excerpt from the book:

P 47 “As soon as Shukri began eating, I left and went to the valley behind

the government building. From there, I climbed to the top of a small hill.

The Armenian cemetery lay beyond that point, but there was no need to

go any further. All the Armenian prisoners lay murdered in front of the

hill, their clothing removed, their naked bodies thrown on top of each

other.

I immediately recognized the old man who always sat in front of the

window. I looked for Onnig, but it was difficult to find him in the bloody

entanglement of naked bodies. I finally found him, barely visible beneath

other corpses. Two strikes of an axe had made his brains fall out.

I could not bear to look any longer.”

My father also wrote:

“There are no Armenian men left in the city. Countless corpses are spread

out all over the city, as well as on the shores of the Euphrates River. All the Turks in the city, without exception, have taken one or two boys or women into their homes as servants. There are about one hundred Armenian women and children staying in the churchyard. One or two of them die every day. Their bodies rot in the yard with a horrible stench. Himut Chavoush, Shavalat Onbashi, and Polis Effendi, have all married Armenian girls.”