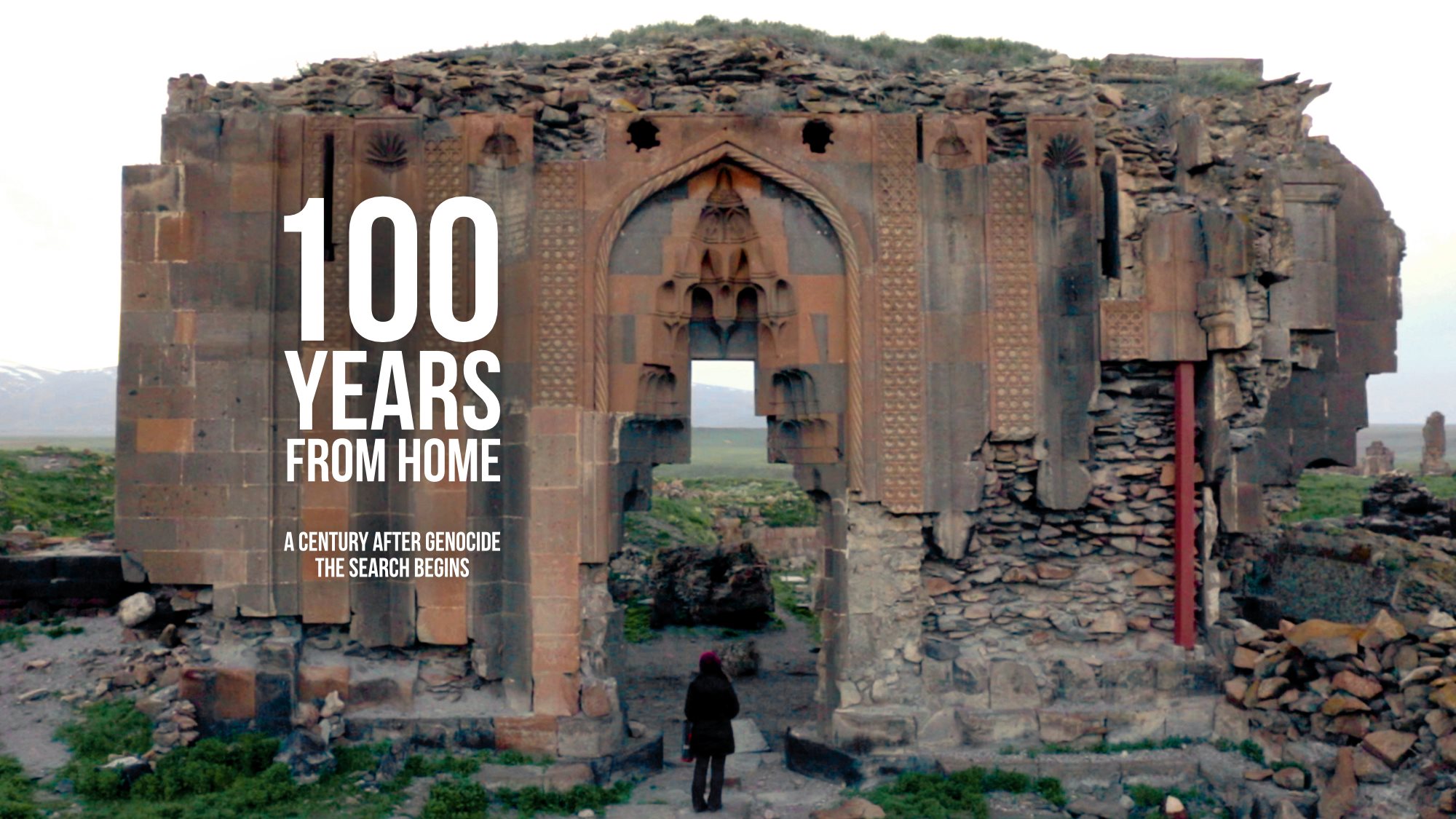

In the documentary “100 Years from Home,” questions chart Lilit Pilikian and Jared White’s journey across the globe. “How do we get over these wounds?” Pilikian asks her mother over the phone, sitting in the stairwell of her house in Los Angeles. “I don’t know how they would feel about me coming into their land searching for my home,” she poses, preparing to travel from Yerevan to historic Western Armenia in Turkey. “How do I fit into all of this?” she asks repeatedly, seeking answers at the end of a map.

In the documentary “100 Years from Home,” questions chart Lilit Pilikian and Jared White’s journey across the globe. “How do we get over these wounds?” Pilikian asks her mother over the phone, sitting in the stairwell of her house in Los Angeles. “I don’t know how they would feel about me coming into their land searching for my home,” she poses, preparing to travel from Yerevan to historic Western Armenia in Turkey. “How do I fit into all of this?” she asks repeatedly, seeking answers at the end of a map.

The documentary narrates Pilikian and White’s efforts to find the ancestral home that her great-grandparents were forced to abandon when they were deported from Kars during the Armenian Genocide. In grappling with the tear left by the events of 1915 on her family history, Pilikian, with the support of her husband White, finds meaning and solace in unexpected sources. The Armenian Weekly recently spoke with the filmmaking duo about their experiences producing the documentary after it made its television premiere on PBS SoCal on September 1st.

Armenian Weekly: When did you first conceive the idea for this documentary?

Lilit Pilikian: Around 2015, getting close to the centennial.

Jared White: At the same time we were talking about…doing a documentary about the Genocide, Lilit had already started to look for her great-grandparents’ house.

L.P.: I had this blueprint that was passed down. My great grandparents built a house in Kars. There was an aerial view in there, and I was using that [to try] to find buildings that were about the same shape and size in Kars.

J.W.: We realized that we could put those two things together, and that her search for her great grandparents’ house and a better understanding of her identity and her place in her family would be a great window into this larger world of the Genocide.

A.W.: The documentary is evenly split between providing historical context for the Armenian Genocide and narrating Lilit’s story. Why did you frame the documentary in this way?

J.W.: In the early ideas of the film, we were going to try and get a bunch of prominent Armenians, interview them, follow them around…look at how they’re living 100 years after this genocide, and how they’re not just surviving, but thriving.

L.P.: A hundred years after a genocide, what happens?

J.W.: [In] early cuts of the film…[Lilit’s] story was a much smaller part of it. We felt like it came off as kind of dry.

L.P.: It was more of a history lesson and less something people could follow along…from beginning to end.

A.W.: That evolution in your conception of the film is interesting.

L.P.: I never felt important enough. I never felt Armenian enough [so we had to find] these true Armenians, these quintessential, pinnacle people.

J.W.: We did get a lot of great Armenians to be in the film. We have Vahe Berberian, we have Pargev Martirosyan, the archbishop, Richard Hovannisian, the great historian, Carla Garapedian, and on and on…[In] storytelling, the more personal you make something, the more universal it becomes. We’ve shown this film at screenings, at film festivals, and we’ve had so many people come up to us, Armenian and non-Armenian…who say I can relate to Lilit’s story, I have a similar story in my family history.

L.P.: And they tell us their whole story usually.

A.W.: Lilit, you mentioned you didn’t feel like you felt Armenian enough to be at the center of the film. When did your mind change about that?

L.P.: Through the process of making this film…Having the opportunity to speak to people from all different walks of life and realize their Armenian story isn’t the perfect Armenian story necessarily, but they still are a representation of us.

A.W.: What do you mean by the perfect Armenian story?

L.P.: You need to be born Armenian, so your blood needs to be Armenian, you live in Armenia, you practice the religion, you speak the language, you marry more Armenians. It’s funny because I’m realizing it’s impossible, because we have two languages. We don’t have the land we used to have. We were forced out of it. We have two sects of the religion. It’s kind of impossible to be the perfect Armenian. One of our interviewees said it best…Your identity is what you make of it, what you choose to be. Another one said, how you feel when you see another Armenian, that connection you feel with the Armenian people. I think that’s what makes you Armenian.

A.W.: At the beginning of the film, you explain that you struggle with embracing your identity as an Armenian-American. At the end, you say you better understand your place “in all of this.” Can you elaborate on what you mean by that?

L.P.: I understand my family story better now. Before I’d gotten it in little pieces and chunks throughout the years. [I actually sat] my family down, recording, [asking them to] tell me the story from the beginning, and from an outsider’s viewpoint. Having Jared there [also] allowed my family to start from the beginning and lay out all the pieces in an understandable narrative…For someone who felt like they weren’t Armenian enough, I’m the first person in my family to have gone back to Kars. I didn’t realize what a big deal that was until I was actually there. Walking the streets that my ancestors once lived on was an experience that brought me closer to them than anything else I’ve experienced.

A.W.: What was your experience like being in Yerevan for the centennial of the commemoration of the Armenian Genocide?

L.P.: It was powerful…They say that it rains every April 24th at Tsitsernakaberd. We checked the weather report and it seemed like it was going to be fine. We brought our jackets with us just in case, but it was hot and sunny heading towards [the memorial]…As soon as we got to the top of the hill and we saw Tsitsernakaberd, it started pouring, really hard, freezing cold rain…So many things were going on in my head. A lot of mixed emotions. Respect for those who came before. Sadness. It was a somber experience.

A.W.: Jared, as someone who isn’t Armenian, what was your experience like being there for the centennial?

J.W.: It was very moving. It’s a funeral procession, really, on this grand scale. It felt very special to be there for that and to be able to help document that in our small way for our film.

L.P.: I don’t want to say the word cathartic, but…it’s this heavy weight that we’ve all carried, and this gives us a chance to explore it.

J.W.: It’s a chance to mourn, to grieve the lives lost. It’s just such an unfathomable number of lives lost that it’s difficult or impossible to mourn or grieve all of them. It’s nice that there is this ceremony that [tries] to pay its respects and recognize this huge void that was left by this tragedy.

L.P.: We march for the people who were forced to march before us.

J.W.: We make that visual juxtaposition in the film. The people who are forced to march out into the Syrian desert during the Genocide, we dissolve from a photograph of that to all of these people marching up to the Genocide memorial to pay their respects to those people.

A.W.: Maps seem to play a large role in the documentary. Why are maps important to the telling of this story?

J.W.: I think that maps are important to understand the Armenian story, because so much of the Armenian story is this ever-changing map…from Tigran Mets being [the] huge empire it covered to what it is today, [a] tiny landlocked country. A big part of the Genocide…was the land that was taken and what was Western Armenia was destroyed.

L.P.: Basically making the language without a homeland. Western Armenia now doesn’t have a homeland.

J.W.: [There are about] 10 million Armenians in the world, and seven million of them live outside of Armenia. The Armenian experience for a vast majority of Armenians today is one where they do not live in their homeland. I think it was Lilit’s way of understanding…a way in to try to find her identity, to find her place in her family history, in her community. These maps are not just of places. They’re maps to meaning.

A.W.: What was your visit to Kars like? How did you feel while you were there?

J.W.: The whole time we were in Turkey, [Lilit] was very nervous and…on edge. So I was trying to be there for her. It was this balancing act of trying to be there for her while following her around with a camera, which was a strange dynamic. Her not wanting to draw attention to herself, but us naturally drawing attention to ourselves by the nature of me following her around with a camera.

L.P.: And by being out at dark…

J.W.: With Kars, I was struck by the fact that…a lot of the Armenian-built buildings are still there and have been repurposed into other things. It felt like walking through Kars was the closest to what it would have been like walking there 100 years ago [compared to] Ani or Van…It felt like it was to some degree preserved in time.

L.P.: The morning we were leaving Kars, we had breakfast there…they had a giant bowl of honey, and they [told us] this is the honey from Kars. When I took a spoonful of that honey, I realized that this honey is as close to something my ancestors tasted in a pure, raw form, because this is from the same hills, and the same flowers, and the same bees that they had honey from. I am tasting a piece of what my ancestors experienced in Kars.

A.W.: Do you think it’s possible to get closure when grappling with such a catastrophic event?

L.P.: I think it’s not so much closure for the Armenian experience that I’ve obtained. It’s more of a closure in the sense that I have a better understanding of how I fit in all of this, and how I’m a part of all of this. Closure doesn’t necessarily mean it’s done and set and has a bow. Closure is an understanding of it…[having] found a sense of home, a sense of belonging in the community.

J.W.: I think the experience of making this film brought us closer together, because we would go through some experience and I’d be filming it, and afterward I would say, tell me what just happened, what were you going through, what emotions were brought up. It was almost a form of therapy we were going through where she was having to—

L.P.: Grapple with these issues that I never would have had it not been for this documentary.

A.W.: Lilit, you say you found a sense of home and belonging in the community. What is home?

L.P.: Home is the people. It’s my mother. And this guy (pointing to Jared)…I’ve been watching the documentary over and over again non-stop, so it’s been a very emotional week with my mother. She passed in the making of the film…[home is] the people. It’s a sense of belonging.

A.W.: What has been the response to the film from audiences?

L.P.: Very warm responses all around. Everyone who’s seen it has usually wanted to come up to us and talk about it. We’ve had anything from Armenians telling us their personal stories, to people who are non-Armenian saying they can relate to their family’s immigrant past…Everyone I think wants to connect with their ancestors and know a little bit about their identity and where they come from.

J.W.: It’s a universal American experience where, especially newer immigrants to America or children of immigrants to America…feel like they have one foot in where they came from and one foot in America. In the process of making this film, I keep coming back to the importance of truth, especially in this day and age. When countries don’t recognize the Genocide or deny that it happened like Turkey does, it gives tacit permission to other countries to commit further atrocities. Not speaking up about it, not calling it what it is, a genocide, is not just wrong, it’s dangerous. Sadly there are still genocides happening around the world today. The best thing that we can do to fight against that is to talk about them, to shed light on them, to fight against them, and to hold people accountable for them. I didn’t learn about the Genocide in school. I learned about it through friends like Lilit who told me about it. I wanted other people who were like me to know that this happened and to know that we need to tell the truth about what happened and to not let things like this happen again.

“100 Years from Home” will air on KCET on Saturday, September 19th at 9:30 p.m. P.T.

Request “100 Years from Home” from your local PBS member station.

The hatred of Armenians in Turkey is by design. It is manufactured hatred by the terrorist Turkish state. It is a form of defense mechanism, through turning unsuspected Turkish population into Armenian hating public, to deny the 1915 Armenian Genocide in order to not only get away with mass murder but to hold onto stolen Armenian properties, assets and occupied territories. By manufacturing hatred through institutional brainwashing and by fabricating history Turkey is turning its population into “loyal” guardians of stolen Armenian properties.

The Armenian Genocide and the loss and confiscation of the 90% of the total Armenian landmass, a.k.a. occupied Western Armenia, are forever tied. In other words, the preplanned and state-sponsored Armenian Genocide was put into action in order to confiscate the Armenian homeland in Asia Minor as part of the forced Turkification of the region AND/OR in order to put an end to the Armenian people’s dream of living free from Turkish occupation the occupied Armenian provinces had to be devoid of their indigenous Armenian populations. Plain & simple!

Western Armenia is neither “historic” nor “Turkey.” It is occupied Armenian lands.