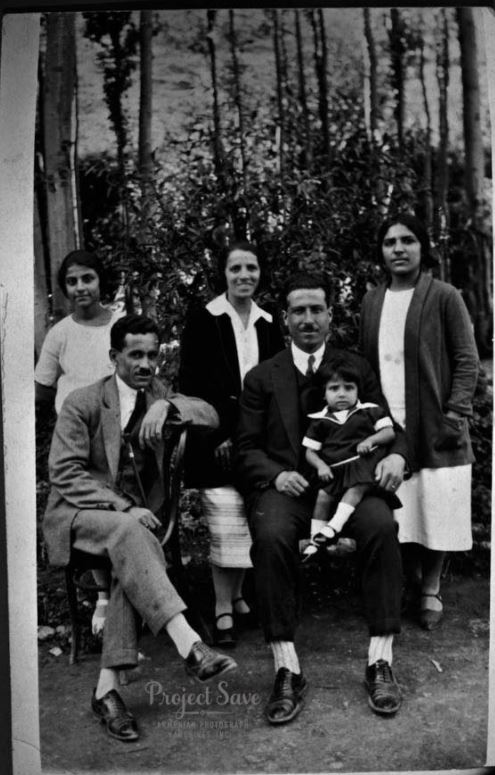

In 1924, Lousaper and Anna Kussajikian were reunited after years of painful separation through a photograph. The Kussajikian sisters were born in Marash in the Ottoman Empire and survived massacres that claimed the rest of their family members. Lousaper joined the Near East Relief as a young refugee and worked as a nurse midwife at several facilities in Syria. When she sent a photo of herself to a friend in Cyprus, the photo ended up reaching her sister Anna at a Near East Relief orphanage in Greece. Lousaper arranged for Anna to be brought to Beirut, where they lived until they immigrated to Watertown, Massachusetts in 1929.

The incredible story of the Kussajikian family is one of many in a collection of photographs preserved by Project SAVE. Project SAVE’s archives include photos of Lousaper in orphanages with other young refugees, in clinics with members of the medical staff and seated alongside her sister and friends. These are just a few photographs of the nearly 45-thousand amassed by Project SAVE in the past 40 years.

The idea for Project SAVE was born 50 years after Lousaper and Anna Kussajikian’s story, in the 1970s in the United States back when Ruth Thomasian was a costume designer in New York City. She was asked to work on a theatrical play set in 1890s historic Armenia. When she couldn’t find photographs for visual research, she went straight to the source.

She spoke with with senior Armenians, many of them survivors of the Armenian Genocide, visited their homes, looked through their old photo albums and listened to their stories. She was struck by how enthusiastic people were to share their photographs that otherwise might be lost, forgotten or destroyed. “I can always be a costume designer, but I can’t always have these people, eager and willing and able, to talk with me,” Thomasian stated in a recent interview with the Weekly. So she left the theater and founded Project SAVE with the goal of salvaging Armenian photographs from the dustbins of history, a project that would occupy her for the rest of her life. “I followed my instincts, which means you follow what your soul tells you to do,” she asserted.

Project SAVE has since flourished into a historical resource for Armenians to connect with the hidden stories of their ancestors in a new and tangible way. This week, 45 years after its founding, Project SAVE launched an online collections database, where people worldwide can search among hundreds of photographs and access rare images. This is the first time the public will be able to view and interact with these historical photographs and learn about their origins, who is pictured and what they were doing at the time. “Our mission is to preserve these photographs and the people and the culture so that they can be seen and shared,” explained Project SAVE executive director Tsoleen Sarian.

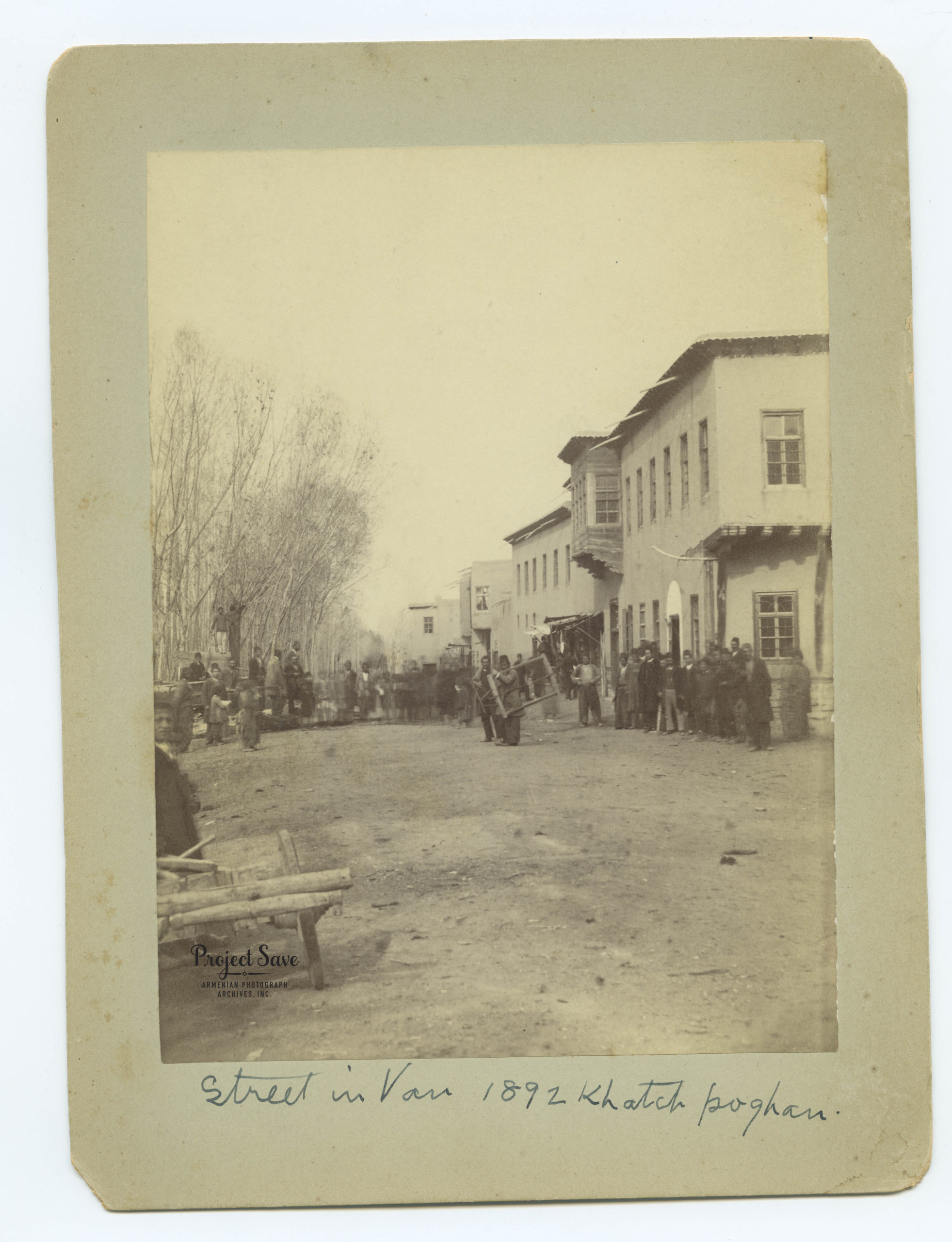

The Project SAVE collection captures a cultural heritage by composing a visual catalogue of Armenian practices and customs across time. The database is far more in-depth than posed portraits paid for by wealthy families. They also offer glimpses of quotidian routines: people meeting in the streets, children attending school, trading at the marketplace. They depict average people outside the purview of history working, eating, celebrating and moving through life together. Project SAVE is committed to celebrating the positive aspects of Armenian culture and allowing for the continuation of life through the preservation of photos in order to “help us see, literally see, who we are as Armenians and the contributions we’ve made to society globally,” as stated by Sarian.

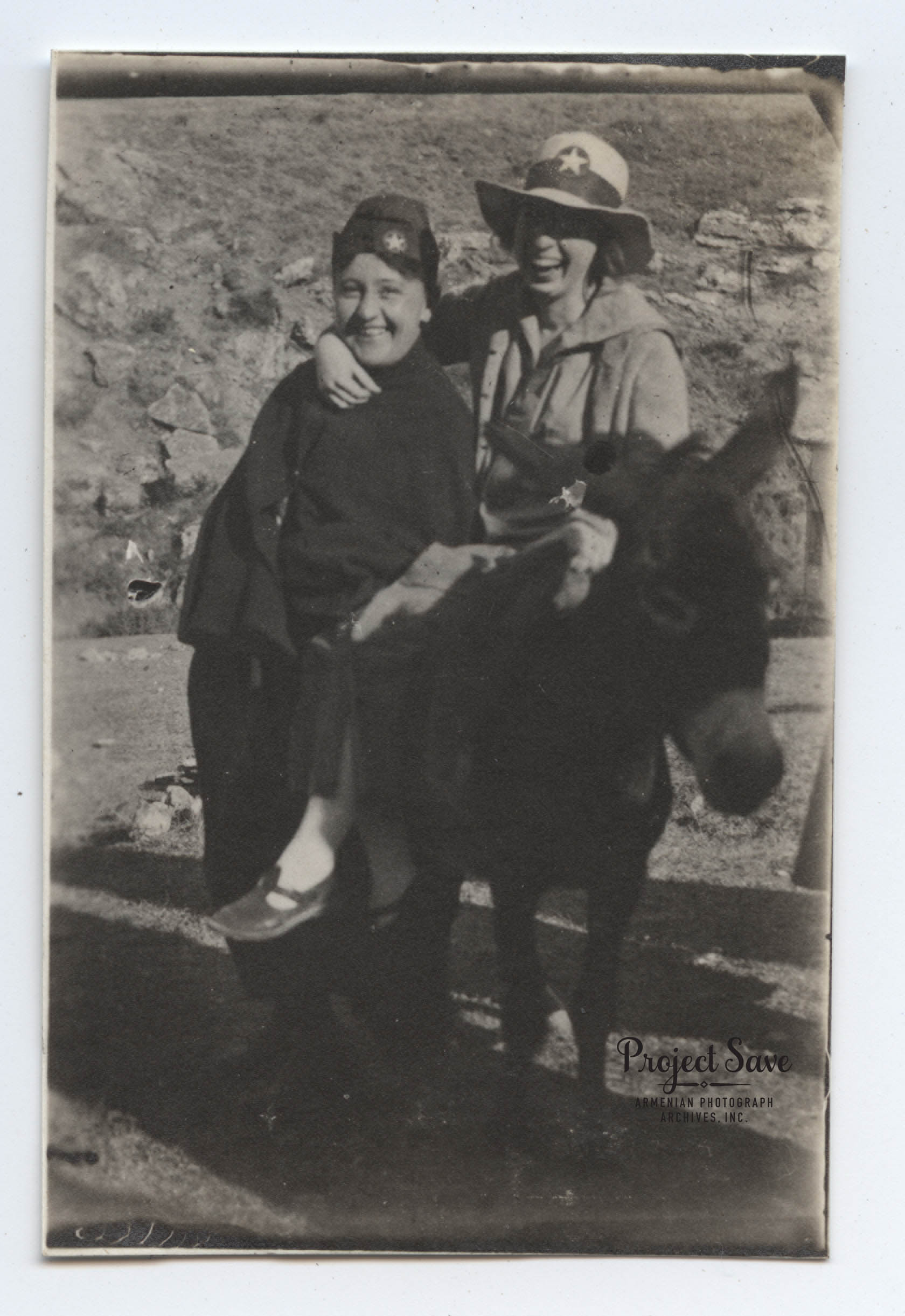

This undertaking is perhaps best reflected by the Missionary collection, the first photo gallery to be digitized and released alongside the online collections database. The Missionary collection, consisting of 500 photographs captured between 1900 to the 1920s, includes photos taken by Christian missionaries deployed in the Middle East and Near East Relief workers. It is unique in that it offers an intimate perspective into the lives of missionaries and Armenians during a time frame from which images are difficult to come across. While photography was banned during the Armenian Genocide, missionaries from the United States were equipped with personal cameras and took the opportunity to document their experiences and observations.

The Missionary collection provides an expansive look into a complicated period of history. The photographs document the encounter of East and West, like the differences between the missionaries’ and locals’ styles of dress. They also exhibit interactions between different communities, including Armenians, Greeks, Turks and Kurds, in shared communal spaces, like a marketplace. They expose images of resilience and altruism, depicting people at refugee camps and the volunteer physicians who tended to them.

These photographs constitute relics of a distant past, yet they are also in conversation with the present moment. This collection not only illustrates a dynamic and rich image of a particular place and time 100 years ago, but it also has a broad impact in shedding light on imminent questions that concern people around the globe.

The photographs include representations of refugees in the Middle East, an issue that is eminently relevant as the number of displaced persons around the world continues to rise. They demonstrate inspiring service on behalf of missionaries who uprooted their lives in the West to travel to sites of atrocities in unfamiliar lands to offer their humanitarian assistance.

In contemplating the collection, Sarian reflected on the Armenian government’s commitment to provide aid to Lebanon in light of the recent explosion in Beirut. This pledge is rooted in a history of receiving and offering help in times of suffering, encapsulated by the exchange between missionaries and survivors of the Armenian Genocide and other massacres revealed in the photo collection. “I think about what we had to go through as a people and how we did and how we continued to contribute and thrive,” Sarian remarked. “It’s inspiring to see how people helped us and how we continue to help.”

The photographs also complexify modern readings of history by providing diverse and unexpected portrayals of everyday life.

“In this picture, I don’t know who’s Armenian, who’s Turk, who’s Kurd,” Sarian stated, referring to one of the marketplace photographs. “They’re just people. No one’s running away. No one’s being hurt. It’s just people at the market.”

This diversity is further rendered in other photographs documented by Project SAVE outside of the Missionary gallery. Photographs collected from throughout the twentieth century across continents reflect a myriad of Armenian histories. The cultural heritage they preserve resists homogenizing notions of a single Armenian experience. They push back on the idea, for example, that the Armenian community just includes wealthy elites, by representing working class Armenians from all sectors of society.

The photographs simultaneously testify to the threads that unite an incredibly heterogeneous global community. Photos from Armenia and throughout the vast diaspora reveal continuities in cultural elements such as dance, food, music celebration and other traditions across space and time into the present day, as exhibited in a previous digital gallery Our Armenian Spirit. The result is a photographic heritage that attests to an expansive and ever-evolving understanding of Armenian identity.

Such photos can connect with people living in cities as different as Buenos Aires, Argentina and Glendale, California with large Armenian populations, as well as with those living in areas with little access to other Armenians. They establish links between Armenians residing in countries like Syria or Iran today and 100 years ago. They might resonate with Islamized or hidden Armenians, Armenians who don’t speak the language or practice Christianity and Armenians who identify as mixed race. They do so by unearthing photographs and stories that reveal similar cultural practices at the heart of Armenian identity that transcend facile or constructed distinctions.

“The more images people have of what it means to be Armenian, the broader [and] more cosmopolitan we can make that definition,” Sarian asserted. “That’s why it is important to be able to have an archive, a place where these photographs are collected so they can be shared.”

This viewpoint speaks to the importance of the new online collections database. In forming the digitized archive, which will grow and develop over time, photographs are not only preserved, but also held, catalogued, documented and shared widely.

History does not exist in the past. It is internally contested and in continuous dialogue with the present. The formation of a living, thriving archive of photographs opens up newfound possibilities for studying history by allowing the public to directly interact with its records and reflect upon their bearing on the current moment.

It also personalizes the discipline by setting forth multitudinous narratives of the hidden individuals who comprise history, whose names traditionally cannot be found in history textbooks.

Thomasian studied history as an undergraduate student, but says she was dissatisfied with the way the discipline was presented to her. With Project SAVE, she is pursuing her preferred type of historical narrative: people history. “People history is really about having conversations with people. It didn’t start academically, because academics don’t really talk with people to gather their information. They stay in their ivory buildings and don’t get out among the people,” she explained. Through Project SAVE, Thomasian and the organization’s other team members have the opportunity to create a new mode of studying history by redeeming the memories of regular individuals and recognizing the importance and value of their distinct stories for future generations.

“The idea of these images, a lot of them are unknown. Unknown places, unknown people. But their image is still important. Somehow, I think of it as helping them come back to life almost,” Sarian claimed.

This hope extends into Project SAVE’s endeavors to make the photographs widely available and usable. Project SAVE collaborates with organizations like the Shoah Foundation to create curriculum about the Armenian Genocide. The database will be available for teachers and researchers to search for primary source material on topics ranging from immigration to fashion. Finally, Project SAVE shares images from the database on social media platforms such as Instagram to bring them to new audiences. These initiatives all reflect the aim to amplify these historic photographs within the Armenian community and beyond.

The title of the organization stands for Project “Salute Armenian’s Valiant Existence.” Thomasian chose the word “save” before creating an acronym, because she was keenly aware that she was saving people’s stories by providing detailed attention and care to documenting photographs that are too often overlooked and thrown away. The acronym was born as an ode to the Armenian Genocide survivors whom she first interviewed for the project and their undeniable courage.

Yet the meaning of the name extends beyond this group of people. The project honors Armenian ancestry by placing individuals whose narratives have been neglected or threatened with erasure at the center of history. It saves Armenians today by connecting them with their past and extolling the diversity and wealth of their heritage.

“These people are not lost and forgotten,” Sarian upheld. “Like you and me, they had families, they had jobs, they had parents, they had children, they studied, they worked, and they left a mark on this earth, and their image survives.”

Be the first to comment