I remember the day unger Michael first walked into my office at the Hairenik headquarters in Watertown, Mass.

“So, you’re the new guy in town? From Canada, right? We’re going to breakfast. Let’s go,” he said in his soft but stern voice.

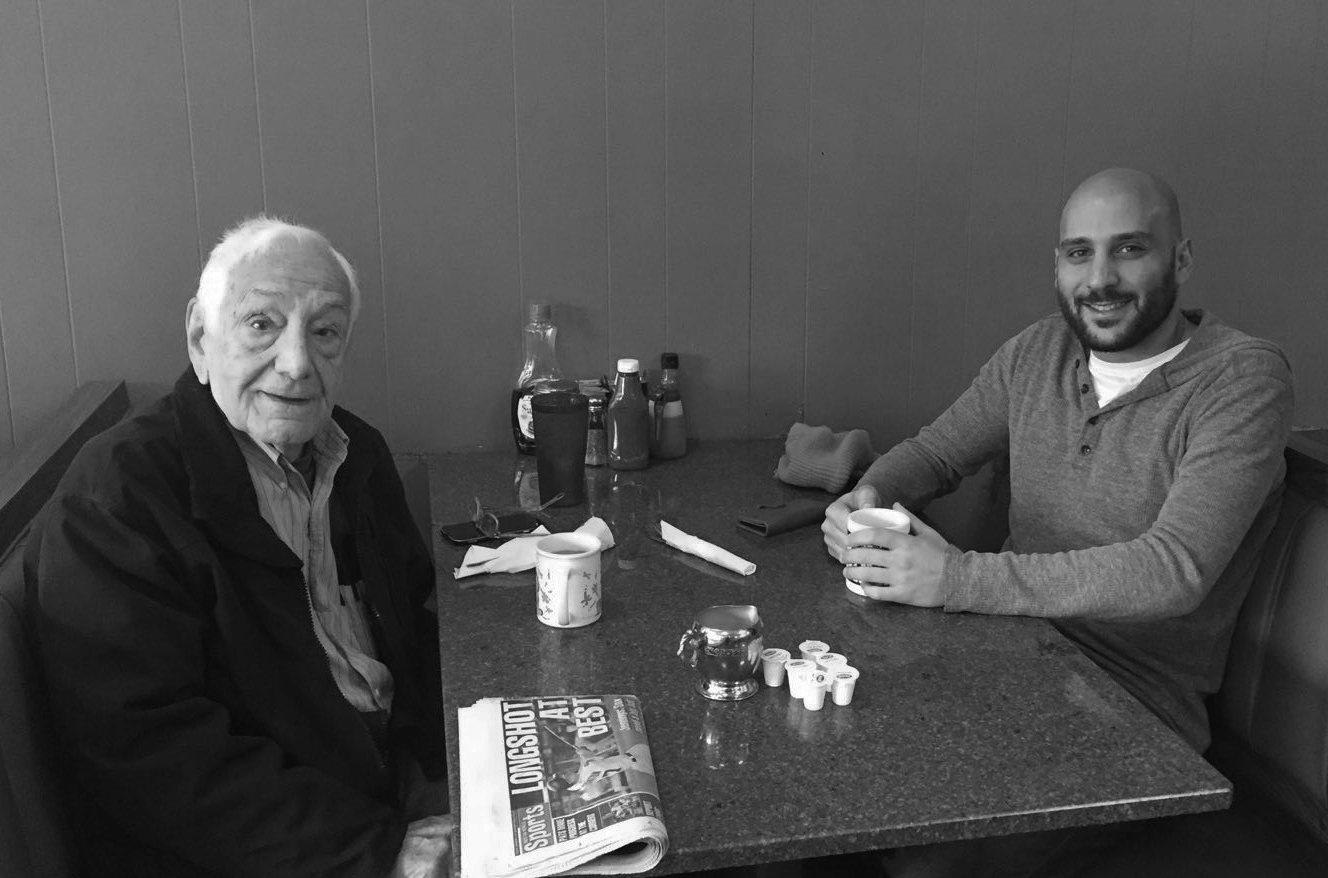

I had arrived from Toronto only a couple of weeks earlier to serve as the assistant editor of the Armenian Weekly. It’s safe to say that I didn’t have many friends in the area. A few of us from the office piled into unger Michael’s Jeep, and we were off to his beloved (and now-shuttered) Watertown Diner. That day, I met a man I knew previously only through his byline in the Weekly.

Our biweekly Thursday outings soon became a much-revered tradition. Sometimes we would have breakfast in a group, but very often, it would just be me and Michael.

On more than one occasion, fellow patrons at Watertown Diner (and later the nearby Uncommon Grounds and Newton’s Village Café) assumed that Michael was my grandfather considering the several decades between us.

During our breakfasts, I learned about a man who had about a million stories—from his days serving aboard the USS Lyman K. Swenson in WWII to his adventures across South America—but preferred to listen to others; an esteemed and celebrated professor who was never afraid to say “I don’t know” and always wanted to learn something new; a dedicated community member who didn’t shy away from constructively criticizing the missteps of his beloved Armenian organizations; and a devoted family man who cherished his children and late wife more than anything in the world.

Michael was kind and honest. He was a staunch supporter of the rights of the people of Artsakh and would rather be in Armenia most days. Armenia and Artsakh were special—even sacred—for him. His several insightful, thought-provoking and timeless op-eds about the future of Armenia and Artsakh, as well as about often-ignored topics such as domestic violence and violence against women in the homeland, continue to inspire and challenge his readers.

But from the countless articles of his I would have the pleasure of publishing during my days at the Weekly, his proud musings about becoming an Armenian citizen at the age of 89 would perhaps stick with me the most. Aside from the sentimental reasons he lists for deciding to apply for citizenship, his sober, pragmatic approach is one that has influenced me greatly and helped shape my perspective. “The more ways each of us is connected to our country, the more valuable in the aggregate we become,” he wrote in that piece. “In turn, a dynamic and secure Armenia is the source that nourishes our far-flung communities in the Diaspora and their incoming generations from morphing into an unidentifiable mélange of humanity.”

Michael would often say that he had very few regrets in life. “The thing I probably feel sorry for the most is the fact that I’m not fluent in Armenian,” he confessed one October morning, with a genuine melancholy in his eyes. Like always, he had told his favorite waiter to come back for our order after our second cup of coffee, just enough time to catch up on the past two weeks. That day, however, it was clear that he would rather reminisce. We spoke about his father, a topic Michael had averted for the most part. Michael Sr. had passed away when unger Michael was only eight.

During that conversation, the question of his family name came up; I asked when and why his family name came to be spelled Mensoian in English, since the name was Մենծոյեան in Armenian, which should be spelled “Mentzoian” in English. Was it meant to simplify the spelling? Was it intentional? He wasn’t completely sure.

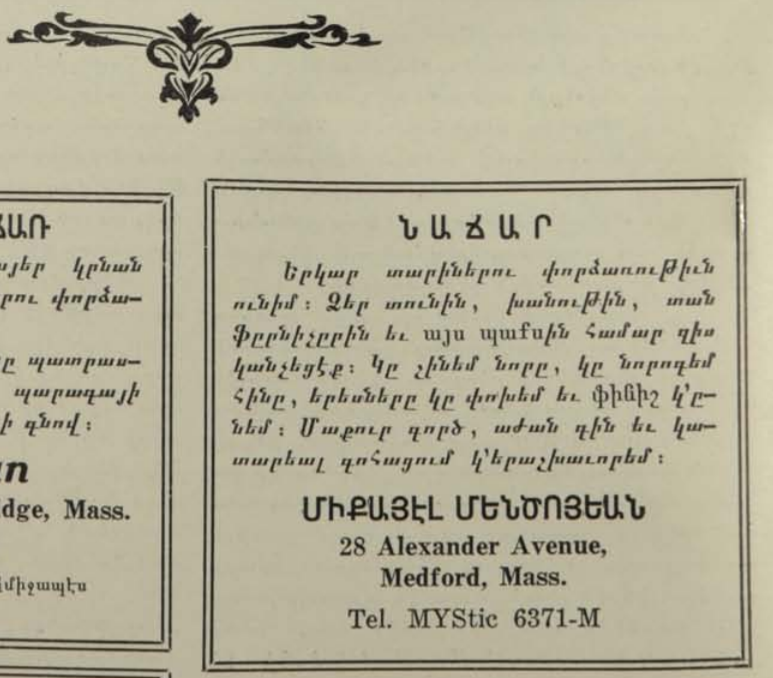

This was the first time I saw him weep—softly, discreetly, and only for a few, quick seconds. I wasn’t sure how to react. I didn’t know how I could possibly console someone more than 60 years my senior. Scrambling, I promised I would see if I could dig up any information on his family name when I got back to the office. My impatience got the best of me, and I had to Google it on my phone right then and there. We were both surprised when we found an advertisement that his father, Michael Sr., had taken out in the April 1932 issue of «Հայ վաստակ» (“Hai Vasdag” – An Armenian Commercial Review), published in Boston, Mass. Michael hadn’t seen that ad before.

The Armenian ad read: “CARPENTER – I have many years of experience. Call me for your home, shop, home furniture, and ice box. I build new, repair the old, change surfaces, and finish. I guarantee clean work, a low price, and complete satisfaction. Michael Mentzoian, 28 Alexander Avenue, Medford, Mass. Tel. MYStic 6371-M,” which I translated aloud.

“Well, I’ll be damned,” he said, with a smile on his face, and we went on with our meal.

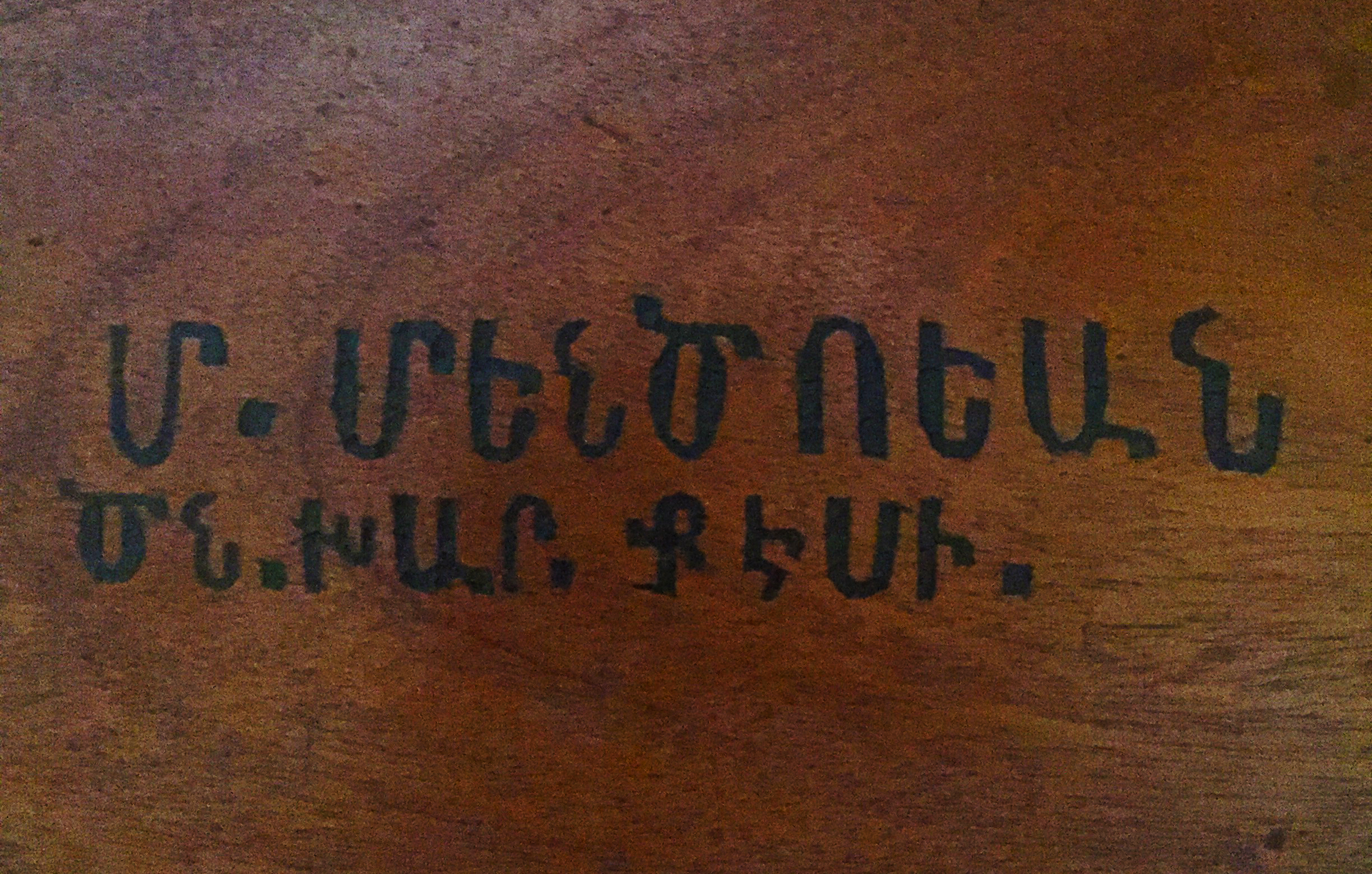

The following week, unger Michael showed up to the Hairenik right on time. He called, like he always would, and told me he was waiting in his Jeep in the parking lot and that I shouldn’t rush. When I got to his car, he said that we would be taking a detour that day. A short drive later, we arrived at his beautiful home where he had lived for several years. After touring me around and showing off trinkets and keepsakes along the way, we arrived at a beautiful wooden dining table. Michael dug his knuckles into the solid wood, gave it two knocks and asked me to pop my head underneath.

“It says Մ. Մենծոեան, ծնած Խարբերդ, ՔԷսրիկ,” (M. Mentzoian, born in Kharpert, Kesrig) he proclaimed proudly in Armenian. “It might not be much, but at least I can read that; I can read my father’s writing,” he said. That was the second and last time I saw him cry, just as softly and discreetly as the first. This time, though, he couldn’t hold back the tears. And neither did I.

After my move to Boston, Michael became the grandfather I had lost just two years earlier; he became the father from whom I was several hundred miles apart; the older brother I always wanted and never had; and a true friend and comrade—an unger—with whom I could share anything.

The last I spoke to unger Michael was on Father’s Day, a couple of weeks before his passing. I called him from Toronto to ask how he was doing considering all that was going on in the world. He declared he was “just great” without hesitation. “As long as you young people are well, I’m just great,” he said.

There may have been several decades between us, but I never felt it for a second. He was a true and sincere friend. I am forever grateful for meeting Michael, and I am certain that his memory will live on in his daughter and son, Martha and Chris, his friends and family, his countless students, his fellow community members, and in all the hearts that he touched throughout the years through his contagious smile, his thoughtful words, his insightful articles, and kind, goodhearted presence.

Be the first to comment