Many American Armenians live with a fear. It is not the type that causes medical concern or even impacts their livelihood. It is a future fear. Will my children and grandchildren retain their Armenian faith and heritage, or will they disappear into the vanilla American melting pot? At face value it is a legitimate concern for a diaspora community 100 years removed from the original indigenous immigrants—the majority of whom escaped the Genocide of 1915-23. A diaspora sustains itself generation to generation. When examining the probability of this new type of “survival,” we have a myriad of causes from intermarriage to an increasing secular society, to the impact of an over-materialistic society. There are sociologists who says it is normal and predictable for assimilation to reduce the ethnic retention in the diaspora. It is clearly the greatest challenge that the diaspora faces because every other problem assumes that there will be a viable community to address the visible problem it faces.

A viable community requires a critical mass of individuals who identify with the culture. The long and short of it, it is the reality we live with that starts and ends with the individual. One irony of this dilemma is we rarely make it personal. The core strength of the Armenian community is the Armenian family, yet we avoid focusing on the family as a solution. We tend to direct our energies to the community, its resources and our collective ability (or inability) to address our problems. There is nothing wrong with this focus except it doesn’t get to the root cause.

Obviously the community must provide the core resources for education, identity mechanisms and activism. How many times have you heard we have a wonderful priest or an awesome youth organization, but my children just don’t care? It’s more about what is missing. We are born into families and later join communities. Our values and learning are driven by our family experiences. I look forward to the day when we have advanced sociological research on the Armenian Diaspora, but based on my experience and intuition, I believe that there is a direct relationship between the family activity and individual long-term identity. This is the mirror to which we can begin to find the answers to our fears.

Let’s take the Armenian church as an example. It is the most important institution in the diaspora and has been responsible for establishing a sense of community with Armenians in all of the diaspora. It is also the subject of grave concern relative to leadership, vision and relevance. There is, however, another view to consider. It would be humbling but productive for us look in the mirror while we work to improve the effectiveness of community institutions. Are we taking personal responsibility or simply assigning it to others? Our faith begins and is grounded by a personal relationship with Our Lord Jesus Christ. Essentially, that process starts when we are born. Who is responsible for sharing with our children?

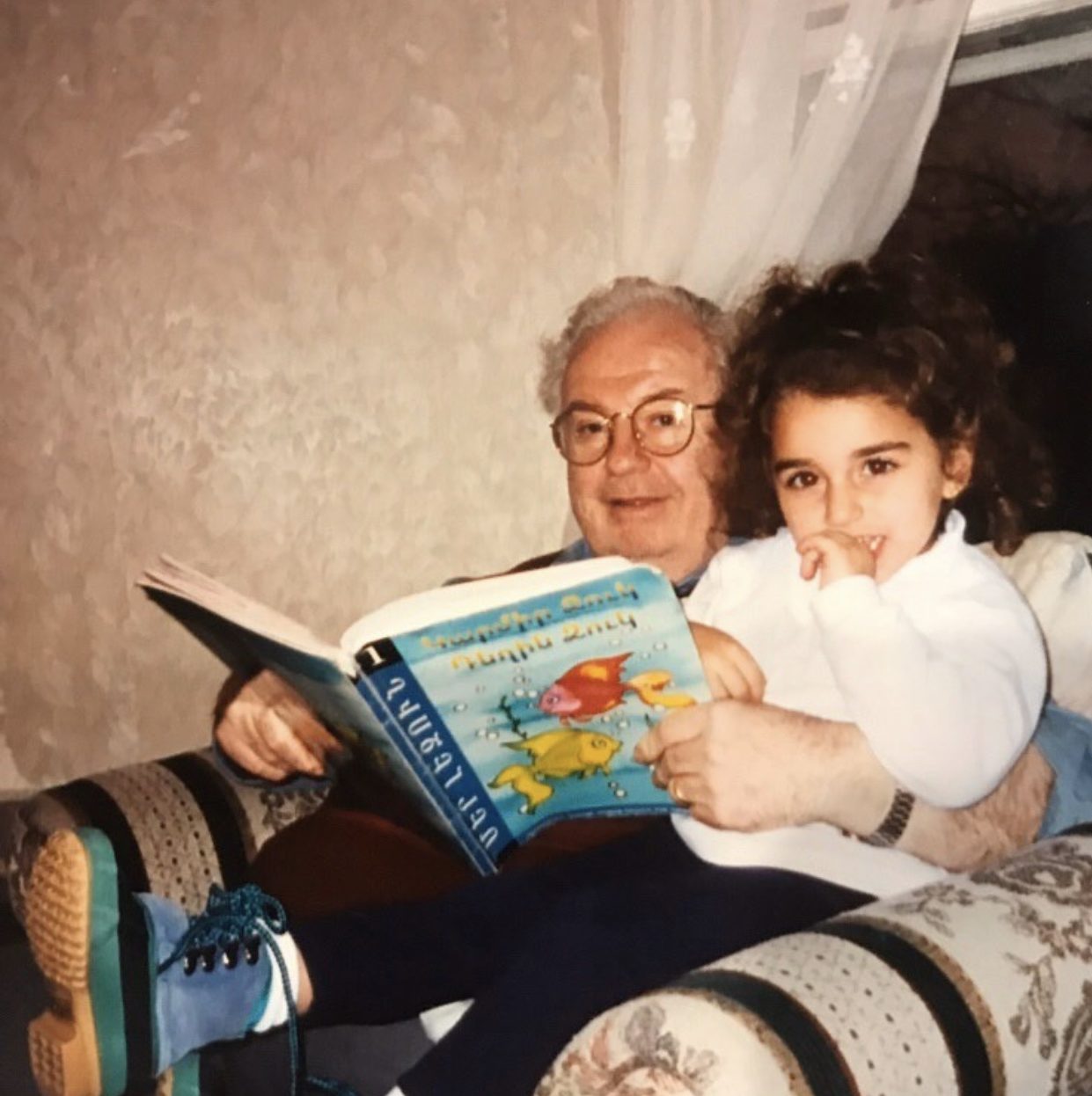

I would like to focus on two very important “institutions” in God’s family structure: parents and grandparents. Parenting is about sacrifice for those who are dependent on them for their development. Just as our children require food and shelter from their parents, they also need spiritual nourishment, values and an identity. God has provided an additional resource in grandparents. Having gone through the process and pondered their mistakes, grandparents offer a wise, calm and constant source of love. Just when we feel overwhelmed by the task of raising children, grandparents provide a needed outlet that brings joy to the children and relief to parents.

Let’s put this in the context of establishing a relationship with the Armenian Church. It actually is quite simple for the children, but it does require a sense of priority for the parents. Just bring them to church regularly! Not when they are six or seven, but as babies. Let the congregation hear the wonderful sound of a church with a future as babies fuss. Don’t be embarrassed. It is inspiring. Let these children hear the beautiful hymns early and often in their lives. You want your children to have a connection to the church. Bring them! If you can’t attend on a given week as parents, then this is where grandparents come into play. Repetitive experiences early in their lives are an investment that will instill interest later in life. If participation was not your priority in their younger years, it makes no sense to lament their aloofness as young adults. The next time we want to sleep in, go skiing, take the kids to soccer or are angry at the priest, fast forward the video 20 years when you wish you had chosen a different path. Life is about making choices. We need to develop a way to talk about parental choices as a community without it feeling overly critical. Priests should not fear “upsetting” people if they give them loving advice. I look at it this way… I would want my friends and family to give me advice about what is in my children’s best interests. Perhaps that’s the problem. Too many of us do not believe that spiritual development and identity are important enough to make the priority list. As parents and grandparents, that is something we need to think deeply about.

what memories are we creating for our children and grandchildren?

I consider myself very lucky. My father was a deacon of the church and my mother taught Sunday School for 50 years. My sisters and I didn’t have any choice. I remember the deep sense of pride watching my father on the altar over the years. Years later my own son in my arms would yell “Papa” to my Dad in church. When I was six, I handed out roses and recited a greeting to then Archbishop Paroyan (later Khoren I of Cilicia). I can still feel the smooth cloth of his vestments as hugged me. My maternal grandfather was a deeply spiritual man. I vividly recall holding his hand as we walked into his parish, St. Stephen’s of New Britain, and he would teach me how to pray in church. In his later years, I watched him pray every night as he went to bed. We don’t forget these moments. These are moments that influence our future. The question is what memories are we creating for our children and grandchildren? Do they include our beloved faith and church? We have the opportunity to mentor them into a future filled with substance and a solid foundation.

Another area of importance is our heritage. An ethnic connection gives our children a sense of identity, self-esteem and the ability to contribute to sustainability. If our children are to identify with their heritage, it must start early through their parents and grandparents. In other words, it begins in the home. Take an inventory of a regular week in your home. Do your children see you as Armenian role models who commit time and advocate for important aspects of our heritage? One particularly exciting area is family history. Teach your children your family lineage and relationship with historic Armenia. How did they arrive here? The more your children are informed, the greater the identity linkage. It is sad when I meet young people who have little or no working knowledge of their family tree. There are great resources today in genealogy and village life (Houshamadyan) in historic Armenia that can connect the missing links in your family’s past.

If our children are to identify with their heritage, it must start early through their parents and grandparents.

My own experience with heritage identity began when I learned of my paternal grandfather’s experience as a “gamavor” in the Armenian Legion. I was young, but the stories I heard of his courageous life and exploits as a patriot inspired me to dream and read. It was my parents and grandparents who gave me this gift. Sometimes we overcomplicate this role. It doesn’t require financial resources, advanced education or special skills. It’s all about relationships. Nearly all children adore their grandparents. There is a special bond that creates this unique relationship. Imagine the possibilities as grandparents discuss their family history, their village lineage and other aspects of our culture with their grandchildren. Bilingual skills make children feel special and important. Even if our beautiful Armenian language is not spoken as a primary language, it has an important role in the lives and identity of your children. Armenian music, both instrumental and vocal, as well as dance offer natural identifiers for children.

The common denominator in all these options is you: the parents and grandparents. Once you decide it is important, success is waiting for you. It takes strength to resist the temptation to skip church, prioritize activities or simply lead a life when you always think there’s tomorrow. Consider the previous generations and the strength they displayed in this regard. I wouldn’t have the opportunity to write about this challenge were it not for our predecessors. We like to talk nostalgically about prior generations. If we retain one aspect of their memory, let it be that they understood the importance of parenting. They understood the concept of sacrificing today for a better tomorrow. Clearly stated, they did what was necessary to give their children a better life, which included their faith and heritage. The question is…will that continue to be in your parental portfolio?

God does not have an ethnicity and associated heritage, so it is a bit strange for Mr Piligian to be presenting God as a parental surrogate to preserve Armenian ethnicity and heritage. But is more strange to see religious commentaries in a newspaper, sitting uncomfortably next to factual stories and reportage. There are pulpits and church newsletters for this sort of material. But for here, stories about the Armenian Church – yes; sermons from the Armenian Church – no.