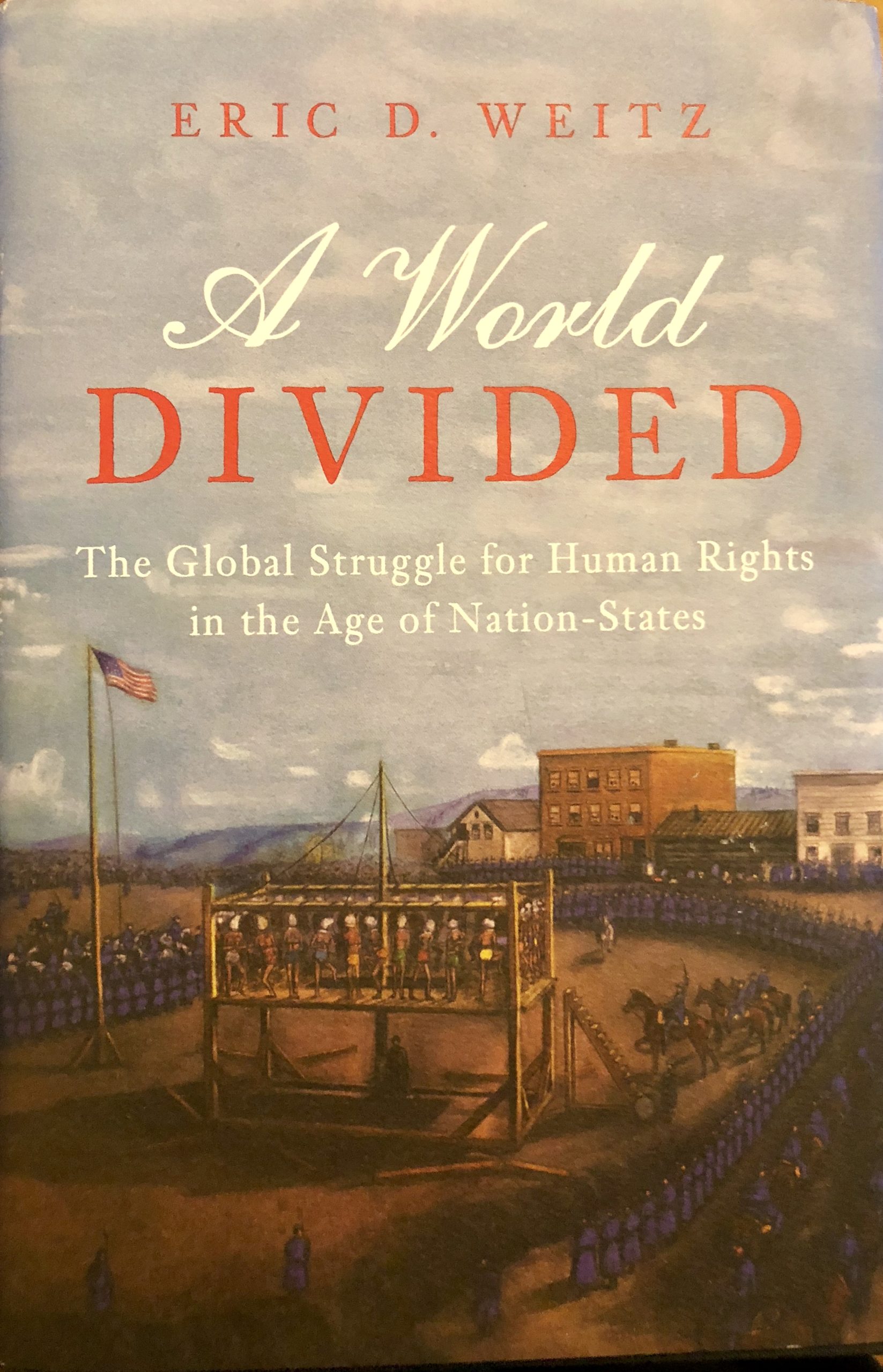

The following is an excerpt from Dr. Weitz’s book, A World Divided: The Global Struggle for Human Rights in the Age of Nation-States (Princeton University Press, 2019).

The following is an excerpt from Dr. Weitz’s book, A World Divided: The Global Struggle for Human Rights in the Age of Nation-States (Princeton University Press, 2019).

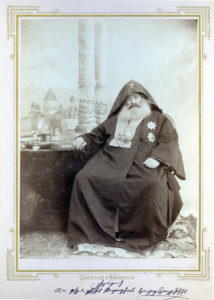

On 27 June 1878, Catholicos Mkrtich Khrimian of the Armenian Apostolic Church wrote to the German Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. He and his colleague, Archbishop Khorine de Nar Bey, had been charged with expressing the “voices and aspiration of Armenians in Turkey” to the Congress of European states that Bismarck had convened. The Catholicos included with his letter a cache of documents that explained the “rights of Armenians,” the same rights that have been accorded other Christian populations of Europe. The documents also supported the Armenian claim for wide-ranging autonomy within the Ottoman Empire. Khrimian then called on Bismarck to “invoke your protection in favor of [the Armenian] nation.”

The Catholicos’s submission to Bismarck and the Berlin Congress marked the debut of Armenians on the global political stage. Never before had they been represented at a congress of the European powers. Never before had their concerns and interests been so clearly expressed to an international audience.

Two weeks prior to the Catholicos’s letter, two representatives of the Alliance Israélite universelle had also written to Bismarck. The condition of Jews, especially in Romania and Serbia, was dire, Charles Netter and his colleague Kann explained. Despite pledges and agreements in the past, Jews throughout the region lived under continual persecution. Kann and Netter argued that only upon the principles of international law, the equality of all men, and religious liberty could peace be secured in Europe. The two representatives enclosed a memorandum signed by twenty-four Jewish organizations and individuals that called on the Berlin Congress to secure the rights of Jews, and thereby the peace of Europe.

Unlike the Armenians, Jewish representatives had been present at earlier European conferences, at 1815 in Vienna and 1856 in Paris (to resolve the Crimean War). That representation had been limited to a few notables, the grand, wealthy men like the Rothschild brothers, Moses Montefiore, and Adolphe Crémieux who had entrée to European princes, prime ministers, and kings. Their type was present in 1878 as well, notably in the person of the German-Jewish banker and Bismarck confidant Gerson von Bleichröder. But now, far more extensively than ever before, Jewish representatives mobilized public opinion and arrived in significant numbers in the host city of an international congress.

Armenian and Jews became the quintessential minorities in 1878 as nation-state foundings and empire flounderings in the face of nationalist movements moved to the very center of European and global politics. Armenian and Jewish representatives believed that Great Power recognition would provide them a lifeline of support and the rights their people deserved. Backed by the major European states, Armenians and Jews would be able to live in peace and prosper all across Eurasia.

Minorities have existed only for the last 150 years. They are the creation of the nation-state, the dominant political model of the modern era. In the nation-state model, the state, in most instances, there are of course exceptions, represents one particular ethnic group, whether defined by language, religion, ethnicity, or skin color. Anyone else — Armenians in the Ottoman Empire Jews in Poland — becomes a minority in someone else’s state and therefore a “problem,” an irritant to the supposed unity of the nation.

That had not always been the status of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. Until around the mid-nineteenth century, they had been the “most loyal millet.” To be sure, Armenians suffered from discrimination and some episodes of violence beforehand. But the Ottoman Empire in its heyday, from around the fourteenth into the eighteenth centuries, also accorded Armenians a good deal of autonomy. Some had even risen to high positions within the state bureaucracy. No Ottoman sultan, nor Russian czar or Chinese emperor expected all of his (and occasionally her) subjects to practice one religion, speak one language, and be of one ethnicity. Empires, unlike nation-states, were by definition multiconfessional, multilingual, and multiethnic.

All that began to change in the nineteenth century, the grand era of nation-state foundings all across Europe. Even the remaining empires — Ottoman, Russian, Austrian — struggled with developing nationalist sentiments and movements within their domains. The policies of the empires varied, but under Abdul Hamid II and especially the Young Turks, the response was clear — a reassertion of the Turkic (not just Muslim) character of the empire, a policy that could only endanger the Armenian and other Christian communities. Moreover, over the course of the nineteenth century, some Armenians had prospered. International trade in the Ottoman Empire was largely in the hands of Armenians and Greeks. Well-to-do Armenian families sent their sons to Paris and London to be educated and acculturated into Western ways and to run branches of the family businesses. While only a small sliver of the Armenian population, these more prosperous Armenians aroused the intense ire and envy of Ottoman Muslims.

We can date the creation of minorities to the Berlin Congress in 1878. Bismarck convened the Congress to resolve rebellions, wars, and territorial disputes in Southeastern Europe. All the major European powers were present and even the United States showed up as an observer. Along with Armenians and Jews came many other representatives of what we would now call non-governmental organizations (NGOs), including American Quakers and missionaries, British abolitionists, Muslim villagers from Greece. They arrived from as far away as Philadelphia and Istanbul, sped along by the new modes of transportation and communication, the steamship, railroad, and telegraph. They crowded Berlin’s hotels and rooming houses, wrote memos and newspaper columns, held rallies, and deluged the German Foreign Office with letters and petitions. They stalked the hallways and courtyards of the meeting sites, seeking audiences with prime ministers and their advisors. Armenians and Jews, in the forefront, created a new model of lobbying by an ethnic group.

What did they want? More than anything else, they wanted their grievances recognized – and alleviated — by the Great Powers. As the nineteenth century progressed, Armenians suffered land seizures and violence from Ottoman authorities and Kurdish bands. Jews wanted an end to the severe discrimination they suffered in the majority Christian Balkan lands.

The Great Powers responded, but for their own reasons. In the effort to secure the stability they so fervently desired in a region prone to spark international conflicts, they made Romania, Bulgaria, Montenegro, and Serbia sovereign nation-states. But at a price. Each of the countries had to agree to establish freedom of religion and equal citizenship rights for all people living in their territories, and that meant primarily Jews. The Ottomans regained some of the territory they had lost to Russia in war, but they also had to pay a price. They, too, had to promise equal citizenship rights for all those living in their domains. Even worse, from their vantage point, the Ottomans, in article 61 of the Berlin Treaty, had to agree to improve the conditions of life for Armenians and to allow the Great Powers to monitor the situation.

Jews were ecstatic, Armenians left Berlin with mixed emotions. Armenians had not achieved autonomy, their major goal. Still, their appeal for redress and recognition had been affirmed by the Great Powers. Article 61 gave Armenians the support for which they yearned, the protection of the West and Russia. Now, they believed, the persecution and discrimination Armenians had suffered would be alleviated. Similarly, Jews believed that the provisions for equal citizenship and religious liberty would become reality. Jewish leaders profusely praised and thanked Bismarck, and trumpeted that theirs was a victory for all humanity and the principle of justice.

While the Berlin Treaty did not use the words “minority” and “majority,” by 1900, those words had become commonplace, along with phrases like “minority problem,” “minority rights,” and, specifically, “the Armenian problem” or “the Jewish problem.” In 1919 at the Paris Peace Conference after World War I and at the Lausanne Conference in 1923, those concepts moved to the very center of domestic and international politics, and there they have remained down to our present day.

Despite their high hopes, the conditions for Armenians in the Ottoman Empire and Jews in Eastern Europe only worsened over the next few decades. Their recognition as minorities — whether or not the word itself was used — proved to be no panacea. Just the opposite. Both groups came to be seen as the ever-present irritant, the minority that by its very existence threatened the coherence, the very life, of the four new nation-states and the Ottoman Empire. And the Great Powers proved to be fickle supporters. Certainly none was going to go to war to protect Armenians or Jews.

That Great-Power lifeline for which Armenians and Jews desperately lunged carried a tag — “minority” — that would lead, ultimately, to the greatest tragedies in the histories of both groups, the Armenian Genocide and the Holocaust.

As the concept of minority defines, it also divides. Populations may be the entitled members of the majority, or they might be cast into the “problem” category of minority. Never are people only individuals; their national and racial identities, sometimes freely chosen, sometimes imposed by state and society, follow them everywhere, and especially into that most critical arena, the right to have rights. The great paradox is that over the last 150 years, human rights and minority activists see recognition of minorities as the path to full participation in society, rights-bearing citizenship, and an end to discrimination and violence. But minority recognition is always double-edged. That recognition can also be turned around to make people victims, sometimes in a very literal sense.

Minority recognition must always be linked, in rhetoric and action, to our common humanity. That is the fundamental meaning of human rights — that all people, no matter what their class, race, nationality or gender, deserve to be treated with dignity and respect and are accorded equal rights, and that no group should be subjected to the scourge of ethnic cleansing and genocide, as was the fate of Armenians and Jews.

Be the first to comment