My interest in Komitas has been evolving since I was a young bride. I used to witness my mother-in-law Kayane proudly show off Komitas’ pictures, which were inscribed to his “sister, Marig.” Marig was Kayane’s mother-in-law. Needless to say, as a new bride, I was embarrassed by her enthusiasm and story. Yet, my interest in Komitas’ story remained.

In 1994, I cut a clip from The Armenian Reporter of a brief article about the French psychiatrist Louise Fauve Hovhannisian’s viewpoint that Komitas was not “mad,” as popularly thought. Being a trained psychologist, I was very interested in mental illness. In 2001, at the New Jersey Psychological Association’s fall conference, I sat in the front row and intently listened to psychiatrist Dr. Richard Kogan play the piano and describe the “mental illness” of Shubert as a creative genius. I thought, “How about our Komitas?”

I then asked my parents who were sifting through the literature they brought with them from Lebanon, to set aside any article about Komitas. They collected literature from the Western Armenian papers.

When I found some personal time during my Fulbright lecturing tenure in Armenia and in subsequent years, I visited establishments where archives and articles on Komitas were kept. They included the National Archives, the National Museum of Literature and Art after Charents, The National Library and the Madenataran (depository of ancient manuscripts). Since then, the Komitas Museum and Institute was founded next to the Komitas Pantheon, where a researcher would find copies of all documents kept at the above establishments. The director of the National Archives was most cordial and generous. He handed me the list of articles on Komitas. In the library hall, I had to give a title, then go to a nearby bank to pay for photocopies and return to the reading room with the voucher. While my research was conducted within 15 years of the dissolution of the Soviet system, Soviet traditions predominated at the National Archives. I appreciated, however, the meticulousness of keeping records that the Soviets were known for. For example, I was thrilled to hold Komitas’ research paper entitled, “Shnorhelin, his time and issues relevant to the time” in my hands.

At the National Museum and Library after Y. Charents, I found information about the Arshag Chobanian Fund, a friend and contemporary editor of the Anahid literary paper of Paris. At the National Museum and Library, I learned that Komitas had two male cousins who were priests, both related to us.

At the Madenataran, I was happy to find Teotig’s Amenoon Darekirks while looking for the essay dated 1916 that Komitas had written upon his return from exile, entitled Azkin Vijageh, which appeared in 1919.

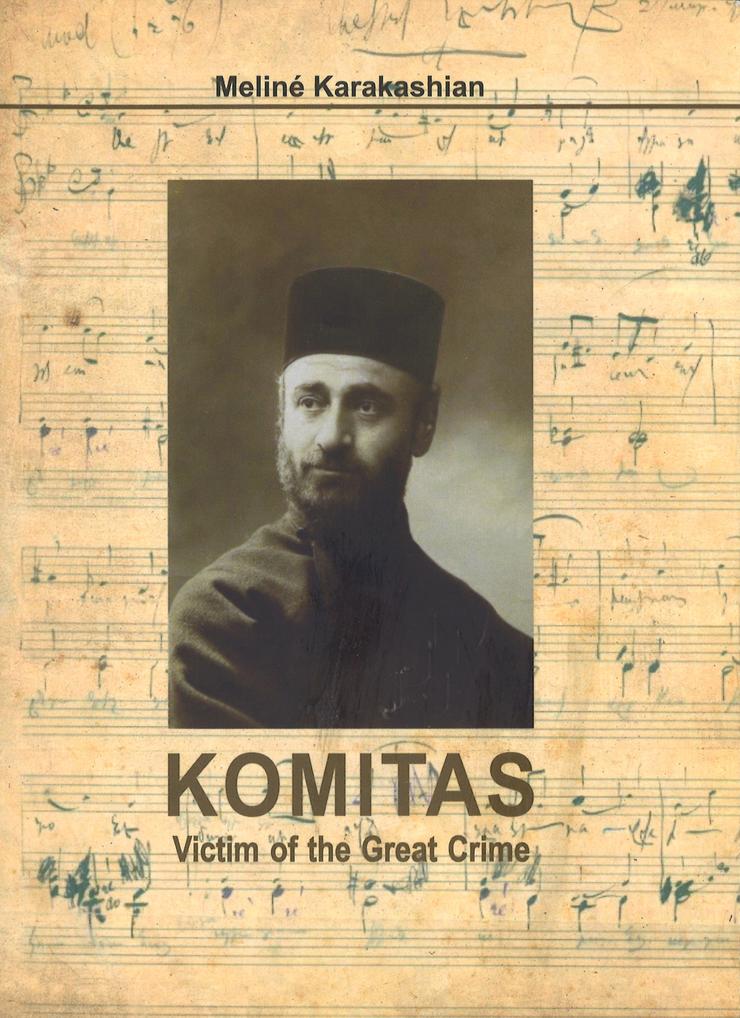

Once my research was completed, my book Komitas: A Psychological Study was published in 2011 by the Catholicosate of Antelias Printing Press and supported by the Carolann Foundation. In 2014, it received the sponsorship of the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Armenia, and the name was changed to Komitas: Victim of the Great Crime.

Komitas had not been lucky, even after his passing.

The next step for me was the task of propagating the story of Komitas, spreading the news that he had not been “mad” and that the Genocide contributed to his symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). His condition was treated in psychiatric hospitals, where Komitas ended his life from a foot infection. While penicillin was available back then, it was not used to treat his wound. Since many patients with syphilis had similar symptoms, syphilis was thought to have been the culprit. I should note here that according to Garo Ushaklian’s writing, permission was taken from the Patriarchate to send a sex worker to Komitas, thinking that sex would cure his ill. Komitas did not indicate any interest in the woman.

Near Paris in the Villejuif Asylum, an ailing Komitas was asked about his illness. He remarked that it was a “family related” problem.

Just then, I realized that I faced the incredible task of going against an established belief that the Genocide was maddening, otherwise Komitas would not have gone “mad.” I realized that the idea of Komitas’ “madness” served a social purpose in Soviet Armenia and the Diaspora. At my first book signing in Yerevan, one writer said, “Komitas was not lucky during his lifetime and during death.” He referred to Komitas’ casket being held up in a Georgian port for a week until his remains were allowed to enter Soviet Armenia.

The Genocide still disturbs us, irrespective of Komitas’ condition. But that writer was right. Komitas had not been lucky, even after his passing. He was used by all as a symbol of Genocide; if Komitas had not gone mad, Genocide would not be maddening!

This was an antiquated way of thinking. In my book, I explained the symptoms of PTSD, well-known nowadays as the human reaction to non-human behavior, namely the threat of death. PTSD is observed after human-made and natural disasters. It is a normal anxiety reaction to abnormal events. Since Komitas was known as an energetic, vibrant person, people could not tolerate the drastic change in him. Anxiety was not known as it is nowadays. Folks thought that he had gone “mad!”

Komitas was a priest, and a large part of his job was to placate people in distress. During and after the exile and the massacres, all he could do was pray. He did not have the ability to “save” people from the atrocities. When he prayed and read Nareg days on end, people in Constantinople considered him “crazy.” He did not have a family to support him. He was a celibate priest who became unemployed during the war. His landlord sent word at least two times to pay rent or be evicted while his housemate had gone to Van to join the freedom fighters in 1914. The threat of homelessness and lack of income following a period of great adoration was hard for Komitas, even though he had promised his aunt “milk giving” Zmrookhd that he would not be weakened by life’s difficulties, that he would always go forward.

Komitas was able to compose The Dance of Moush, which was considered one of his best works during the summer of 1916 at the Harents’ summer home. He considered himself a worthy human being, he wrote, in Harents’ Armenian household. He promised to give a print-ready copy to publisher, Harents; yet, he could not work when he returned home to his reality.

His friend from exile, Dr. Torkomian, decided to hospitalize Komitas from unfounded (to myself) fear of suicide for showing signs of anxiety. In the fall of 1916, Komitas was admitted to the Turkish Military Hospital of La Paix, where in fear of Turkish policemen, he demanded his rights. He was then sent to Ville Evrard in Paris (still demanding his rights until 1922) and from there to Villejuif Asylum where he died in agony in 1935. His body was kept in a casket in the basement of the church—that he wished to serve in 1914—until its journey to Soviet Armenia, viewing and procession to the Pantheon that now carries his name.

Komitas was born Soghomon Soghomonian on October 8, 1869, according to the Gregorian calendar. This week marks the 150th birth anniversary of this musical genius.

Thank you Dr. Meline` Karakashian for your honest article about Gomidas…

You are correct to say … Komitas was not mad … I wrote in my poetry book “Gomidas~Komitas, My Musical Saint” (2017)

that he was severely depressed…He has a photo, which I have included in my book showing unusual anxiety in his look in his eyes after the genocide … It is extremely wrong to use the word “mad”…As you wrote he had Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Under that photo, I wrote…

Gomidas after the Genocide;

See the Look in His Eyes!

I am in shock; I am in fear; I can see blood;

I can see axes crushing my people’s skulls.

How can I sleep?

How can I smile?

Sylva Portoian, MD, FRCP

June 13, 2013

One of Gomidas’ last photos, Constantinople, May 1915. After his return from exile,

scheduled for execution, he was saved at the last moment.