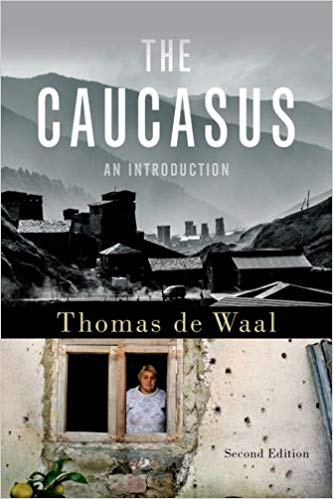

THE CAUCASUS

THE CAUCASUS

An Introduction

By Thomas de Waal

259 pp. Oxford University Press, Second Edition

Two years ago, I arrived in Yerevan, Armenia as part of a five-month-long research and internship experience. Upon landing at Zvartnots airport and taxiing through the quiet, snowy streets of the city, the first thing I noticed was the cold, concrete architecture. These behemoths captured the density and weight of the state, and I felt like I was being watched, much like the British spies featured in John Le Carre’s classic novels. “What have I got myself into,” I asked as I came to the realization that I was now part of a society vastly different from my own, one that was still picking up the pieces after the fall of the Soviet superpower some 25 years before. Thomas de Waal’s book The Caucasus: An Introduction, which released its second edition at the end of 2018, offers a careful historical introduction to this often overlooked, and poorly understood area of the world that I myself am still untangling.

De Waal, a journalist and expert on the South Caucasus has written numerous texts documenting and seeking to understand this complex region. His 2003 book Black Garden, about the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh, remains one of the seminal texts on this topic. The Caucasus, originally published in 2010, visits three countries—Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan—together as a region because he believed they have a shared history. His narrative explains the historical interlocking and contemporary shifts between these three countries.

De Waal is careful to retain a scholarly objectivity in his analysis of the region—important as so much of this literature is written by scholars who have ‘skin in the game,’ so to speak (i.e. scholars of either Armenian or Azerbaijani background)—and argues there is a gap in understanding about this region from much of the outside world. He urges readers to use “zoom and wide-angle lenses” to navigate the last 25 or so years of developments, and particularly in this second edition, cautions against thinking purely in terms of Russia. He is writing as the region is undergoing systemic changes. Internationally, it is being pulled by new, larger powers, which have security and economic interests, while domestically it is being pulled by local interests who are tired of the status quo. A new generation of people lives in the Caucasus, many without the memory of Soviet rule. With each passing year, the Russian “legacy” fades. Students are more likely to learn English, while the ease of personal diplomacy between compatriots such as Vladimir Putin and Ilham Rahimov, for example, will cease with Russia’s next leader. This is the space in which de Waal’s work emerges.

De Waal provides a clear organization in the way he structures his work. Three themes are present: conflicts, culture and connections. The Caucasus has been a turbulent region for centuries. This continues in the frozen conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, countries that have a historical, legal and political interest in the de-facto state of Nagorno-Karabakh. Georgia is not immune to episodes of conflict either. The late 20th century saw episodes of violence in the break-away provinces of Abkhazia and South Ossetia with a re-emergence during the Five Day War with Russia in 2008.

Culture—the second broad theme of this work—provides key insight on the softer flourishing aspects of the region outside the grip of Moscow. De Waal introduces readers to the 19th-century poet Mikhail Lermontov, who helped bring a larger appreciation for the region at a time when imperial Russia was expanding its borders.

Connection is the final theme in this work. Historically the region has been conquered and reconquered through the centuries. Each time a new ideology is weaved into the fabric of the region. Examples include religion, such as state-adopted Christianity in both Georgia and Armenia, established in the fourth and fifth; and Islam in Azerbaijan, over a thousand years later. One cannot ignore other ideologies such as Communism in the 20th century, which acted as a unifying agent.

For someone who has traveled extensively, and has lived, worked and studied in this part of the world, de Waal captures the quintessential themes. His recent work appeals to a niche market of travelers, journalists and those who have a deep appreciation for the region. He encourages travelers in his second edition to escape the Russian-controlled mindset, one I admittedly found myself in during my stay. What would add another dimension to this work is the “pulse of the people.” De Waal illustrates large themes at the state and group level of analysis to describe larger trends. My question is what does everyday life look like for the average person living in these countries? This would have put a greater wedge between the old Russophilic way of thinking and the openness one experiences walking down the streets of Yerevan, Tbilisi or Baku. The Caucasus, writes de Waal, “…is the neighborhood of many places. It’s everyone’s neighborhood.” It’s a tantalizing sentiment, and one which is difficult to acquire in the international news coverage on this area, which tends to focus only on narratives of conflict, as if that were all there is to know.

I have heard De Waal speak at Harvard and read his work.

He may be some kind of British or other agent.

He reminds me of the pro-Azeri propagandist Dr. Brenda Shaffer (she once worked for the Israeli Foreign Ministry), formerly the head of Harvard’s oil company-funded Caspian Studies Program.

Shaffer once invited De Waal to speak at Harvard.

In writing about Artsakh/Karabagh, De Waal has often ignored the fact that over time Azeris ejected all of Nakhichevan’s Armenians – and hence would do the same, and were doing the same, in Artsakh. I believe this is deliberate by De Waal.

This is from his Wikpedia page:

Through his grandmother, Elisabeth de Waal née Ephrussi, Thomas de Waal is related to the Ephrussi family who were wealthy Jewish bankers and art patrons in pre-World War II Europe and whose fortunes started in 19th-century Odessa. He had done some research on the family’s Russian branch, and helped in the researches on family history by his brother Edmund de Waal which led to the publication of the book “The Hare with Amber Eyes”.