Laura Gaboudian walked up to the rusted fence that was guarding a ramshackle and apparently abandoned house.

Could this be it?

Laura, an Armenian American from Rhode Island, was in the Western Armenia town of Havav, searching for the home that her great grandfather had lived in as a child more than one century ago.

Someone checked the GPS coordinates of this house and compared it with the coordinates that were listed in Laura’s notebook. No, this isn’t the right house.

Laura had researched the location of her great grandfather’s home before she had left the US, months before she had begun this Western Armenia adventure.

Now she was accompanied by a pair of self-taught experts in forensic mapping—Nareg Gourdikian and George Aghjayan—both of them Armenian Americans, as well, and all three of them determined to find Laura’s ancestral home.

George had located countless long-lost Armenian churches that had hardly been seen since the genocide, and now he and Nareg were engaged in a mission to help Laura find a long-lost family homestead that Laura’s family hadn’t seen since 1915.

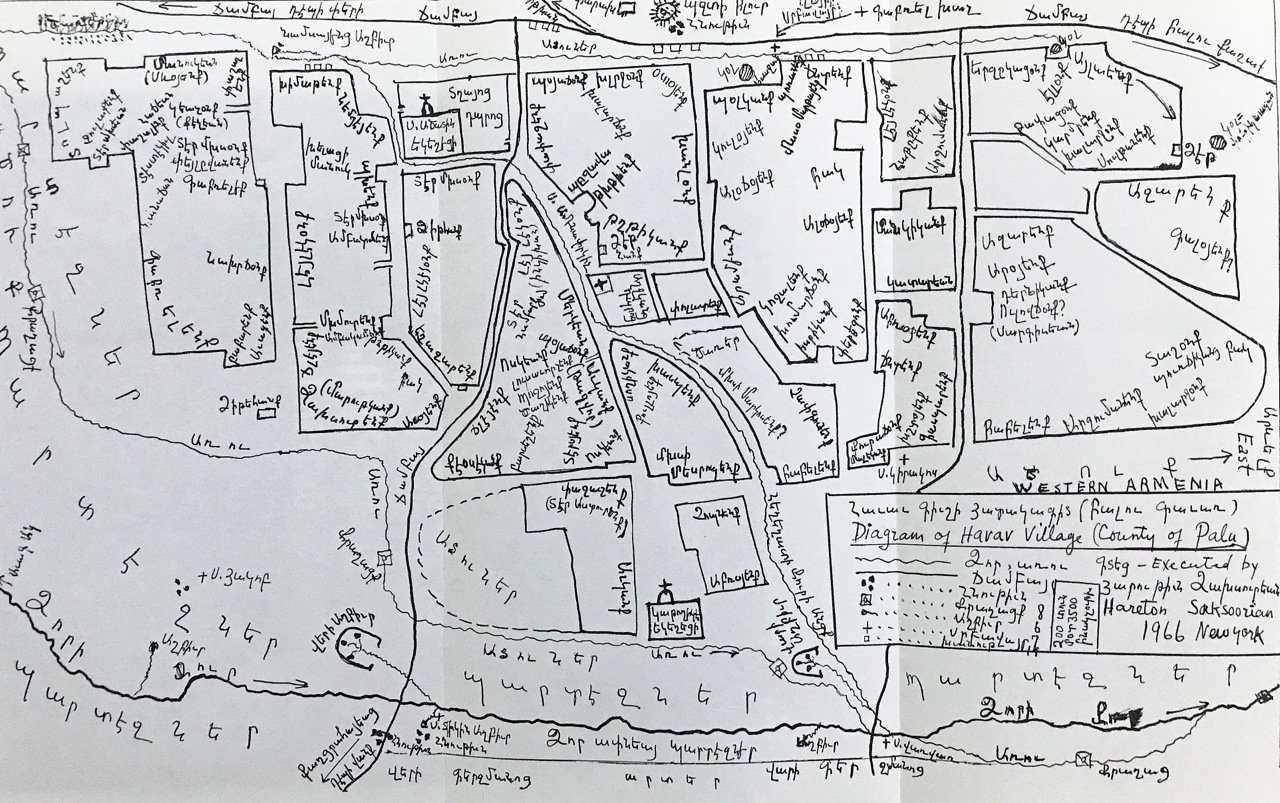

In this case, the forensics were on Laura’s side. A genocide survivor from Havav had long ago drawn a map of the town, and he had marked the location of every Armenian home. George had found the map. And the home of Laura’s great grandfather was clearly marked.

I walked with Laura on this parched street in Havav as she searched for her family home, but my enthusiasm was tepid.

And why shouldn’t it have been? Countless pilgrims, me among them, have searched for the homes of their grandparents in Western Armenia, only to be disappointed. The homes of Armenians, sometimes their entire villages, were destroyed during and after the genocide.

It was midday. It was summer. And there was nothing between the hot sun and us. So we all slowed our pace a notch or two.

But not Khatchig Mouradian. Khatchig had led the expedition that brought Laura to Havav. He looked at the GPS coordinates that Laura was seeking, and he compared them with the GPS coordinates where we were standing.

We’re close, people! Khatchig had a hunch that the house that Laura’s great grandfather lived in might be a bit farther down the street. He picked up the pace and started walking toward a neat two-story home just 50 meters away.

The house was clad in stucco and it had been painted the color of cream of tomato soup. There was a veranda across its front. And now there was a group of six Armenians standing in front of it, as well.

As we stood there, a woman wearing a scarf walked by. We told her why we were standing in front of her home but she refused to talk to us. She entered the house and closed the door behind her.

Within moments, a man emerged and stood on the balcony. He stared at us and scowled.

What did we want?

Khatchig explained, in Turkish. The man didn’t seem interested. He left the balcony and went back inside the house.

Laura and the rest of our group conferred. The GPS coordinates were correct, but we knew this couldn’t be the house that Laura was looking for. Her great grandfather’s house had to be at least one hundred years old. This house was not more than an adolescent.

We stood on the street for several minutes.

After a time, another man emerged from the house. A few words were again exchanged, in Turkish. And then this man, too, went back inside the house.

Khatchig had explained why we had come here. He told the man about Laura’s great grandfather. And he had assured him that we intended to return to the US. We didn’t want to take his house. We were here for a visit, not for a lifetime.

Several more minutes passed. We had been snubbed. Should we leave? And then the first man returned to the balcony.

The skepticism that he had worn on his face had vanished. He invited us for tea. He gave us a tour of his garden. And while we took this tour, the man told us his story.

His name was Sharif Sherifoglu. He and his brother Mehmet lived in the new home with their wives and children. There had been a century old home on the property until about one month ago but it was in bad condition, so the man had pulled it down. He piled the rubble from the old home next to the garden.

His story matched up with the GPS. That pile of rubble was the old home of Laura’s great grandfather.

I looked over at Laura. She appeared devastated. We had arrived 30 days too late. Sharif and Mehmet had torn down her family’s home just one month ago.

As the tea flowed, these two men told us that they, too, had an Armenian grandparent. Their Armenian grandmother had also lived in the old house.

We tried to make sense of the fact that these two Turks had an Armenian grandmother, and that they might actually be Armenians. They talked some more about their lives. They grew excited by their realization that a page from their past may have just fallen into their lives.

But Laura remained silent. If these two men had an Armenian grandmother who had lived in the old house, and if that old house had been the childhood home of Laura’s great grandfather, as well, then Laura may have found more than just an old homestead. She may have also found some members of her family.

Sharif and Mehmet showed Laura the well from which their grandmother had drawn water. Laura took water from the well and splashed it on her face.

Sharif and Mehmet showed Laura their garden. They guided her as she climbed a ladder and picked fruit from a cherry tree.

Finally, Sharif and Mehmet showed Laura the rubble from her great grandfather’s home. Laura held one of the stones in her hand. Had her great grandfather also touched this stone?

As we talked and laughed and shared stories it became apparent that the grandmother of these two men must have known Laura’s great grandfather.

We compared dates—the date when each grandparent was born, and when each grandparent had lived in the old house. And we began to let our speculation wander. We began to believe that it was possible, merely possible, that Laura’s great grandfather was the brother of the grandmother of these two men.

Months later, Laura reflected on that day. “As soon as they told me that their grandmother was Armenian,” she told me, “it all became surreal. I knew that we had to all be related.”

Laura’s great grandmother was born Hripsime Sultanian and was married to Laura’s great grandfather, Melkon Boranian, probably sometime around 1900, in the village of Havav.

Hripsime was, literally, the Havav-girl-down-the-street. Hripsime had grown up in Havav, just a few houses away from Melkon. Thanks to that genocide survivor’s map of Havav, we found the ruins of Hripsime’s childhood home during this trip, as well.

Melkon and Hripsime survived the genocide and eventually escaped to Providence, RI. They had been young adults during the genocide, and they remembered everything. Perhaps this is why they seldom discussed their lives in Havav. They started a new family in Rhode Island and had children, and then grandchildren, and eventually a great grandchild named Laura.

A decade ago, Laura might have left Western Armenia and then spent the rest of her life dreaming: had she just enjoyed the afternoon drinking tea with some long-lost members of her family, or had she merely encountered some friendly Hidden Armenians?

But advances in DNA testing have made it possible for Laura and others to do more than dream about their ancestors. One of the members of Laura’s group, an Armenian American named Ani Kasparian, had brought a genetic testing kit to Havav.

She gave the kit to the two men, and Mehmet agreed to submit a sample of his saliva so that his DNA could be tested.

Several weeks after Laura had returned to the US, the results of the DNA tests arrived. They confirmed what she had suspected.

The DNA of Mehmet matched the DNA of some of Laura’s known family. Laura’s maternal great uncle and Mehmet, she learned, shared many of the same cousins.

Laura attempted to receive the news dispassionately. Sure, the DNA test suggested that she and Mehmet have a common ancestor. Still, further analysis would be needed, she thought, in order to establish a direct relation.

This news opened a Pandora’s Box of information. Laura had traveled to the village of Havav in search of her family’s homestead. She found it, but she also discovered something profoundly different, something she hadn’t anticipated. She also found that a member of her family had apparently been stolen and raised as a Turk.

Laura doesn’t regret taking this journey. But she calls it bittersweet.

The people living today at her ancestral home were so welcoming, so friendly. And yet, she explains, it’s impossible to forget how they came to own the property in the first place, and difficult to accept that a member of her own family was apparently taken, forced to convert, and married off to a Turk.

“I don’t think I was truly prepared for what I found,” she said.

Story and photos reprinted with permission from ‘The Armenian Highland: Western Armenia and the First Armenian Republic of 1918’ by Matthew Karanian (Stone Garden Press, 2019). Available on April 15, 2019 from bookstores and directly from the publisher at www.HistoricArmeniaBook.com

Special thanks to Matthew Karanian for sharing my experience and documenting it in THE ARMENIAN HIGHLAND!

I too had my Grandfather come from Bolis and his name was Dickron Boranian. Althogh we dont have family history one wonders if he may have a Brother?

This story is my DREAM!!!!! I pray that one day, I finally get to go and have the same wonderful experience!

These people are kurdish. You have here armenians coming together with kurds in Eastern Turkey. I do not understand why Mr. Mouradian is not intervening and clearly stating that these people with armenian grandmothers are kurds and not Turks.

Kurds and Turks look the same dark brown people with Iranian a lot of Iranian blood. Most Turks are a mix of Kurds Iranians and Arabs which is why Armenians Georgians are white and Turks and Kurds are brown looking. You are not native To these lands. I can immediately tell when I see an Armenian, then a Turk and Kurd hardly any different. The only Turks that look like the natives are assimilated Armenians Greeks and Georgians of the Black Sea and northern eastern turkey. The rest are kurdish arab looking.

Can, you are right. They are Kurds, not turks. Look how cute the kids are.

The people I interviewed for this story told me they were Turkish. They told me this in response to my question, ‘Are you Kurds?’ They said no, we are Turks. This is why my story identifies them as Turkish.

Can you recommend a travel company that can escort me to the village of Kilis where my ancestors came from?

Tragicomedy ! Turkish ultra nationals will force these people to say that they are Turks for generations than turn around and shun them for doing so.

— MI HISTORIA , TU HISTORIA , LA HISTORIA DE ELLOS , LA HISTORIA DE TODOS …

You can immediately tell how the Caucasian native looking Armenians next to the Turkish/Kurdish mixed people it’s insane how Armenians keep my their ancient bloodline pure. Hopefully will continue to.