Special to the Armenian Weekly

Two recent books from the Beirut publishing house Al Ayn’s “Photographes du Moyen Orient” (Collection Traces) help to fill in cultural lacunae in the Middle Eastern world—gaps created by a crushing succession of colonialism, war, competing ideologies, and refugee camps. Entire traditions have been suppressed or destroyed and individual families have suffered the same fate. These conflicts have also impeded a richer understanding of the wealth of artistic talent present in this region of the world.

Now, perhaps for the first time, the public-at-large and critics can both learn something about the work of two talented photographers, Karnik Tellyan and Hovsep Madénian, both Lebanese-Armenians.

Armenians have contributed in remarkable numbers to the world of photography, from Ara Güler in Turkey and Yousuf Karsh in Canada to contemporary artists closer to home in the United States such as Ara Oshagan, Nubar Alexanian, and Scout Tufankjian. In the Middle East, as Christians and enterprising businesspeople in a Muslim society that shunned working with images and such new technologies, it is not surprising that in the early and mid-20th century, Armenians rose to play a crucial role in this field. From Turkey to Lebanon and Iran, Armenians were at the forefront of the development and expansion of still photography—portraiture in particular. Tufankjian, in fact, recently mused in an interview that perhaps because of their experience of persecution and migration, Armenians have been especially drawn to a medium that seeks to emphasize a certain sense of existence and reality—a proof of their and their community’s existential existence and survival.

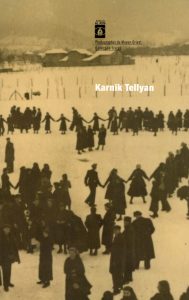

The cover photograph of Karnik Tellyan (Al Ayn, 2017) displays a gorgeous mastery of the black-and-white craft medium. At first sight, we see what appears to be a group of children skating in a large circle holding hands. We cannot make out any of their faces—combined with the snow and the exquisite quality of the paper, the whole almost glows with an ethereal feel. It turns out upon closer inspection that the children and their chaperones are merely out on a winter outing and wearing shoes—not skates. The blurred quality of the photo and the wonderful juxtaposition between the all-black clothes worn by everyone in the photograph and the snowy white surroundings, as well as the geometric nature of the composition (both front center and in the background) arrest the viewer’s gaze. Accustomed as we are to stock images of the Middle East (war, desert oases, harems) it surprises as well: a winter kaleidoscope that might just as well be in the Alps or Vermont.

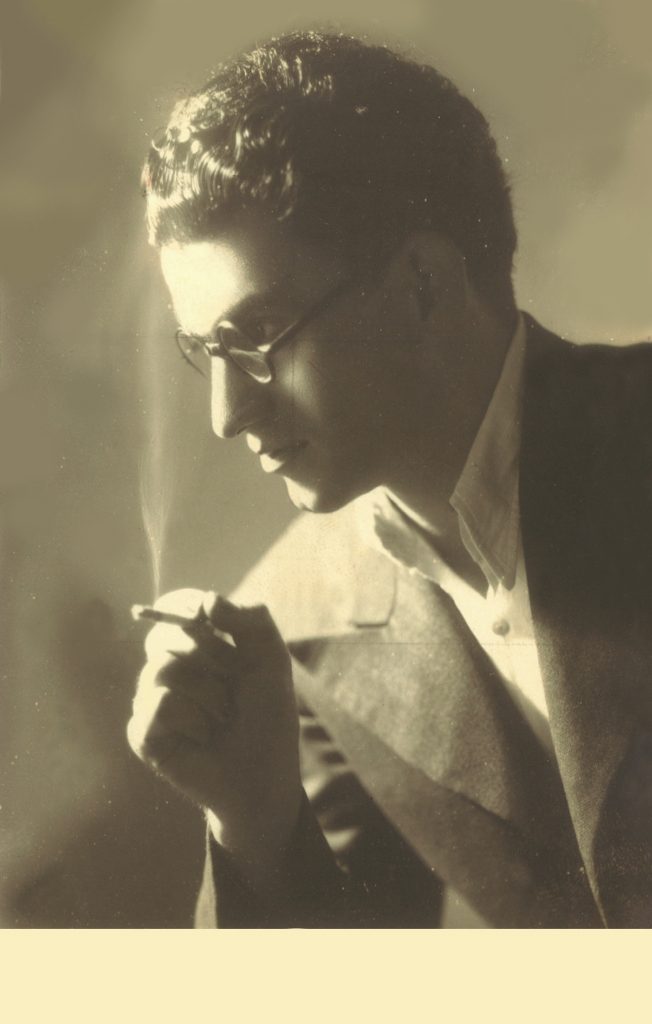

Tellyan’s life story is so full of last-minute escapes from disaster and almost vaudevillian episodes, that it seems almost like a Hollywood slapstick story involving a persecuted immigrant—one, who travels the world escaping death, surviving only to make money and then lose it all through no fault of his own, then finally rises to the top of his chosen profession and establishes studios in three different parts of Beirut. Born in Kayseri in 1904, he escaped the Great Crime or Medz Yeghern and eventually settled in Lebanon. In the ensuing years, he was hired by the German leader in the field, Agfa. He shot several highly-regarded documentary films in Germany, as well as portraits pictures for the military and wealthy families of Iran and Iraq, and then worked again in Eastern Europe and Germany. While in Germany he barely escaped Hitler’s minions and moved on to settle in Lebanon. There, he founded a family and continued his innovations—which were many—until 1985, when the studio closed amidst the corruption and moribund economy that followed in the wake of the so-called Lebanese Civil War.

Tellyan discovered entirely new ways of developing film and was so meticulous, that even his German employers marveled at his work ethic and precision. An essay by the ethnographer and artist Houda Kassatly, which follows on a long biographical sketch of Tellyan’s life, informs us that much of his archives were lost after the closure of his studio: pictures and material were simply thrown out or incinerated by family members and employees who did not realize the ethnographic and historical-artistic value of his photos.

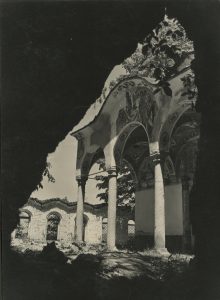

So this book is a rare gift indeed: Pictures of farmers harvesting watermelons; of proud Druze tribesmen; or simply beautifully jagged water filled cliffs—Tellyan captured the essence of these places and people with rare skill. Working 12 hours a day, six days a week, he shot a film on Dervishes in Konya and another on an ethnic minority in Serbia, the Vlachs. His output was prolific even during a certain period in his life when he had to grow tomatoes and other agricultural goods in order to support himself.

But fast-forward to the 1960s and 70s, and Tellyan would be famous throughout Lebanon and the Fertile Crescent. And the photographer was endowed with quite a personality: When Greek priests on Mount Athos refused to be filmed, he simply recruited local boys, dressed himself and the boys as clergymen, and recreated supposedly authentic religious ceremonies.

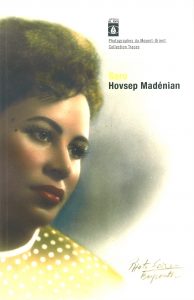

Hovsep Abraham Madénian, also known simply as Saro, was also a refugee of the Armenian Genocide. Born in 1915 in Hadjin, he and his family barely made it from Adana down to Lebanon. After studying at the Armenian Seminary in Antelias and teaching at the Shalieh School in Syria, Saro would return to Lebanon where he became renowned for taking the most dazzling of portraits: Glamorous Lebanese women mainly, posed to look like Hollywood starlets (others mimicking Greek goddesses), wedding portraits, but also family and community pictures that chronicle early Armenian settlements in Greater Beirut and surrounding towns.

But Saro, who passed away in Lebanon at the age of 97 in 2012, was more than a “mere” portrait photographer, though his great talent was—as in the case of Karsh—precisely to lift portraiture to an art form. Saro was also at the forefront of several colorizing processes and techniques. And he was certainly not hesitant to make a yellow shirt more yellow than a canary or a lipstick red even more vibrant than in real life. Some of his portraits seem to portray preternaturally Technicolor worlds, such as the ones that 1950s American Pop and interior decoration also depict. In a move that would today seem peculiar, he also did not hesitate to add in a missing limb on a Palestinian soldier, simply drawing or painting it in. The past, erased, was being re-established.

One goal of photography for Saro was to make the subject beautiful—and his bright portraits were prized seemingly by all. It is difficult to understand today, in an age of endless selfies, how important a role portrait photographers played in the cultural and business lives of entire communities once upon a time. As Kassatly notes in Saro (Al Ayn, 2015), Madénian was also different in that his studios were located in towns outside Beirut—in Bikfaya and the Tarik El Jdideh neighborhood near the Palestinian refugee camps. As she relates, he took photographs of some babies simply au naturel, naked as the proverbial day they were born, while others he attired in tiny intricate cowboy outfits, hat, holster and revolver included. It’s a marvel that he pulled off such kitsch.

Ever the multimedia artist, Saro would sometimes outline his future creations beforehand in charcoal drawings. One photograph of a Bedouin provides a gorgeous ethnographic record of clothing as well as facial features and hair/mustache styles; another is obviously a recreation, the man pictured tall with exaggerated smile and large sash around the waist, the whole bathed in a glowing, greenish tint.

In Saro’s hands, the studio became a stage and any tool at his disposal would be used to create a finished work of art—in a sense, absent the play with gender and narrative traditions, he is more in the line of an early Cindy Sherman than say Avedon, to put things in a contemporary American context.

Kassatly’s biographical and erudite text also provides us with names of other Armenians who paved the way for the art form in the Middle East and whose work we also know very little here in the West. The most famous of these include two Jerusalem monks by the names of Krikorian and Garabedian; Halladjian in Haifa; and Guirogossian, Varoujian, and Sarafian in Beirut.

It’s a breathtaking task to think of the difficult but fascinating work still to be done in bringing them and others to the fore. So much talent, so many critical trails yet to follow.

***

Purchase copies of Kanik Tellyan and Saro at www.loiseauindigo.fr.

Շշմեցուցիչ է:

Ինչպէ՞ս կ’ըլլայ, որ այսքան ատեն մեր այս արժէքներուն մասին մէկ բառ գրուած չէ, երբ անոնցմով կարելի էր սերունդներ ներշնչել եւ ազգային ազնիւ հպարտութեան առիթներ տալ:Պէտք է երախտապարտ ըլլանք հիմա ասոնք լոյս աշխարհ բերող մեր արաբ հայրենակիցներուն:

Let’s not forget Harry Koundakjian another famous News Photographer !!!

He never forgot his Armenian origins !!!

And Ida Kar (Ida Karamian), an important 20th century pioneering photographer about whom too little is written.

In Egypt, Armenian photographers such as Alban, Van Leo and Arman made the great days of photography. One Karaguezian, became the official photographer of King Farouk I and the royal family.

To answer he first comment that was made in Armenian here about why we did not know about these two photographers before and why an Arab publishing house had to teach us about “our own people,” one reason that we did not know about these two wonderful and important artists is simply that Armenians–like it or not–have failed to build any world class institutions like YIVOH and the Jewish Museums for Jews or the Alliance Française(s) in the case of the French etc, yevalylen… We have only ourselves to blame. We build hundreds of churches–many of them empty of the young or the dynamic–and we can seemingly fund endless Armenian Genocide – related projects, but we have forgotten or simply do not know how to organize vibrant modern cultural institutions: so there is simply nobody–or rather not enough people because there is a small core group that cares enough–to even record who all these great Armenian artists,writers and cultural producers are/were. Maybe this will change in the coming 2-3 generations. I certainly hope so. I try my best whenever time permits me to do so, to write about Armenian cultural topics :)

There is an ambitious Armenian American Museum project in L.A; an Armenian Museum in Paris that the government illegally closed down; a failed Armenian Genocide Museum in DC: we need to build all these institutions until they rival the world’s best and also build more schools and endow more academic posts. We actually have the resources and the brains to do these things…the willpower, however, I am not so sure….But as the Italians say, avanti! Haratch!

My grandfather took a lot more beautiful portraits and historic scenes as one of the few photographers who apprenticed for the Iraqi King’s photographer Arshak. My paternal grandfather’s name was Khachig Ohanian born near Ourfa, orphaned at a young age and had his own studio in Baghdad. My father also became a photographer mainly working the dark room and coloring processes by hand and my uncle followed along with myself. My photos have been picked by National Geographic and Arizona Highways as photos of the day some earning 29,000 hearts.