Jora Aleksanyan stood by the half-built hanging bridge and smiled. He was wearing a large straw hat, a jean jacket over a white button-up, and black pants. His dark tan suggested he’d been working in the sun for some time. His eyes widened as he saw the crowned bird I held in my hands.

“I think it’s injured! It won’t fly. I thought maybe you can take it home,” I said.

Before Jora could respond, the bird flew away. “I guess it’s fine,” I blushed, wondering why it hadn’t flown away sooner when we found it on our path.

“We heard your scream from down in the valley, what happened?” he asked.

“We saw a big lime-green snake down by the church!” I said, and extended my hands eight inches wide in exaggeration. I grabbed the camera and zoomed into the picture of the entrance to the 17th-century church to show him the creature.

Jora laughed. “That’s a lodi,” he said. “It’s harmless! It eats other snakes!”

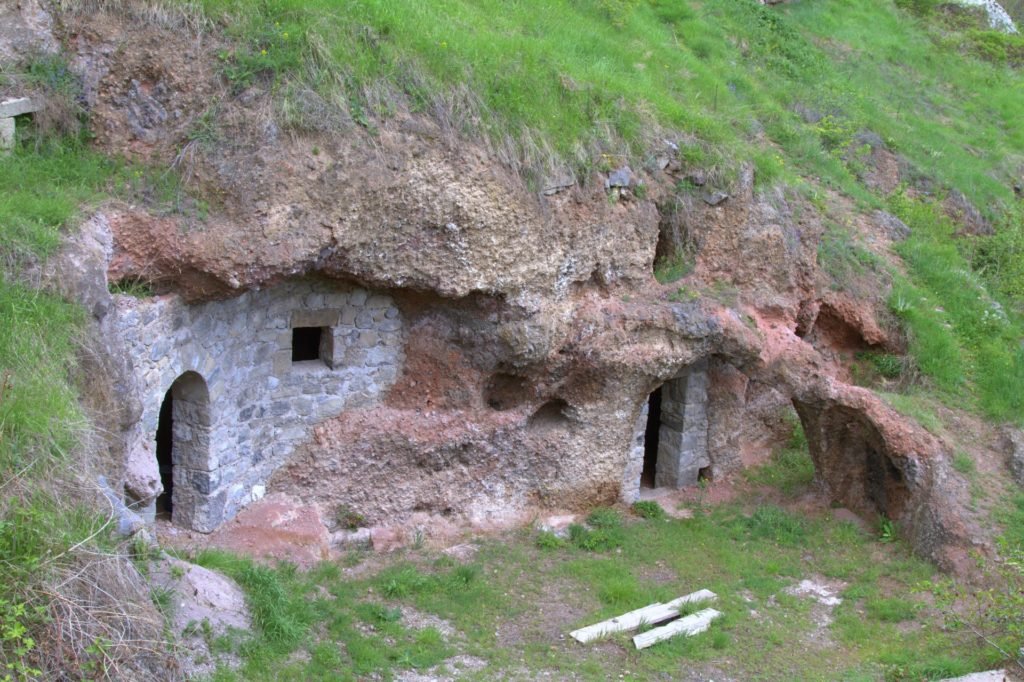

I looked at him puzzled. I didn’t quite understand how a snake-eating snake could be harmless. I didn’t argue. After all, Jora was born in one of the surrounding caves. The cave dwellings—hundreds of them—make up the old village of Khntsoresk, located about 8 km to the east of the town of Goris. In the early 1950’s, the inhabitants of Old Khntsoresk—among them Jora’s family—in search of modern comforts such as running water, relocated to higher grounds nearby and established the new village of Khntsoresk.

“Come with me,” demanded Jora, and began walking on the hanging-bridge. I hesitated, and then followed. He seemed confident despite the steep—63-meter—drop below us, and the rattling steel.

Jora, a local businessman, and his team were pouring sweat and money into the 160-meter-long bridge, built from 14 tons of steel cable, which would soon see hordes of tourists exploring one of the most bewitching cave-villages in the world.

Jora pointed at the caves across the valley, on the side of the mountain. “I was born in that cave,” he said. His cave was on a higher altitude than most others, now abandoned like all the rest. “People wanted to live in stone houses; they didn’t want to live in caves anymore. So, slowly, they all moved out of the valley and onto the hill where they formed the new village,” he explained.

Old Khntsoresk hugs the skirts of two mountains. The valley is about 3 km long. Lacking flat ground, the dwellings were built into the sides of the mountains. Like conventional buildings, the ceiling of one dwelling serves as the floor to the one above. Dwellings in the flatter parts of the valley date back to the 14th and 15th centuries. The rough terrain provided its inhabitants with security, and a self-defense advantage.

Jora pointed to our right: “Mkhitar Sbarabed [General Mkhitar] is buried there,” he said. The legendary 18th-century general fought alongside David Beg, a leader of the movement for Armenian self-determination in Syunik. Following David Beg’s death, Mkhitar took the lead in the struggle, fighting against Ottoman troops in the battles in Halitsor. Hearing of Mkhitar’s victories, the Persian Safavid Shah Tahmasp II recognized the independence of the Armenians of Syunik, and hoped to create an Armenian-Persian front in face of Ottoman-Turkish attacks. Ottoman troops soon launched offensives, weakening Mkhitar’s forces. Military losses gave way to disagreements, and Mkhitar left Halitsor. He was beheaded by Kntsoresk villagers, who betrayed him, fearing his presence would invite destruction to their village.

“Do you miss living here?” I asked Jora.

“Do I miss it?” he smiled, and paused. “Madly…” he finally said, looking in the direction of his cave.

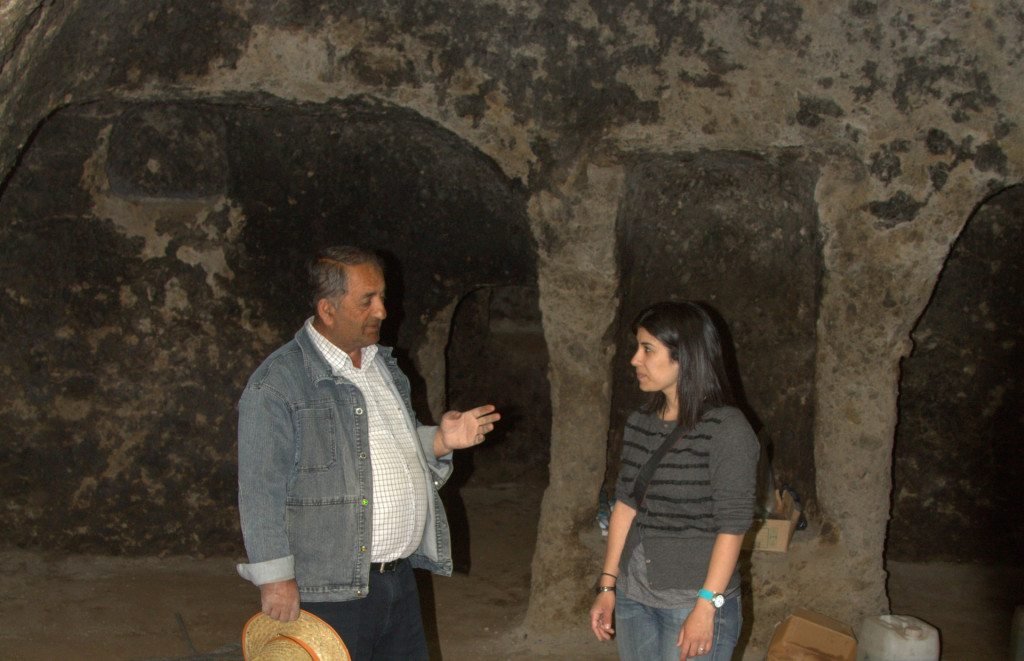

We stood there for a few minutes. He seemed enveloped in nostalgia. When we returned to solid ground, he proceeded to give a tour of the caves.

His head almost touched the ceiling of the first cave we entered. Shelves were carved into one of the walls. A segment of the cave, towards the back, was once curtained off for newlyweds in the family, explained Jora, adding that some households had upwards of 10 members. The circular hole in the ground was the fireplace. A low and round table would be placed over the pit, and the family would sit around the table on pillows, covering their legs with a thick tablecloth or a rug, enjoying the warmth.

Some say Khntsoresk was named for the rich apple orchards in the valley. Others say the original name was “Khortsor” or “Khortsoresk,” meaning steep valley.

In 1913, Old Khntsoresk was the largest village in Eastern Armenia, with 1,800 homes, some of which housed over 10 people. It also had 7 schools, 4 churches, and 27 stores. The town had its own tailors, ironsmiths, bakers, construction workers, and painters.

“We are a very hard-working people,” said Jora. “We don’t accept clothes and food handouts given by the diaspora. We work hard, and we do better than other villages.”

“The diaspora shouldn’t send money, but help in the development of the country,” he added.

Jora sure seemed to be doing his part. The bridge opened on May 9, 2012, less than a week after my chance encounter with him. He hopes his project will increase the number of tourists who visit the area. Already, there seems to be a boom in the hotel industry in Goris—a town that sees high tourism levels as it falls on the path of many who drive through to reach Karabagh. Hopefully, many more will now spend an extra night in the area, and visit the enchanting village of Old Khntsoresk.

*The author consulted the Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia (Yerevan, 1976) for historical information about Kntsoresk.

Nanore; what a wonderful photo of the Eurasian Hoopoe. Thank you for printing it for us. Lucky you to have seen and photographed one. It’s listed on page 37 of Birds in Armenia. It has a slow fight and deep wing beats. When it walks on the ground, its crest is fanned, just as you have caught it. It eats invertebrates. Its eggs are olive-green. I believe that Armenia has a greater variety of birds than any other country in the world! Some of them are simply astonishing in their beauty! We have the most colorful, beautiful, unusual birds in the world. We also have some very rare birds. We have an egret that is extremely rare; an endangered pelican. Can you believe we have a flamingo! Yes, it has long, orange, spindly legs. We have black storks, Eurasian Spoonbills! We had better be careful. We must make certain that we don’t destroy or harm their natural habitats. They are our priceless jewels.

That is exactly why I have decided to go next time exploring such areas, further.

My mother went to Goris Elementary school,before trasnferring to Tbilisi,to secondary and on to Conservatoria…

I crave to be in such areas,have recently become member of the National Wildlife Federatioon in USA and hope to somehow commence cooperation,setting up a branch of same or an affiliate in RA/Artsakh.

I shall need plenty of funding…and I am at a loss to find out how to go about it.I hear some people do fund-raising,to which i am utterly unfamiliar.Maybe my granddaughter may give m e lead.She did mention or my grandson(may he rest in peace) that one friend wAS QUITE GOOD AT IT.WILL INVESTIGATE.

kEEP UP THE GOOD REPORTING NANORE.

Another like you we have in L.A. who does some such work for the y e r e v a n magazine..best to her and to you.

Thank you, Nanore!

Great place! I was there in 2009 for performances and Masaer classes in Kapan and Goris and have taken some incredible photos of the caves where Armenians lived… Until recently…. And the huge dolmens nearby and near Goris.

The people were incredible too. I met some wonderful people there. The museum? Did you go to the museum in the village square in Khntsoresk?

Amazing place. This brought back memories…

Thanks for sharing

Those caves and their inhabitants are covered in a National geographic article, I seem to recall, from 1909 or thereabouts.