Book of the Week:

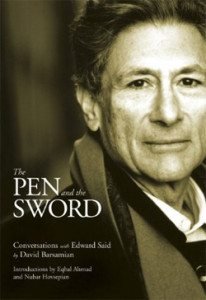

The Pen and the Sword: Conversations with Edward Said

By David Barsamian

Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books, 2010: 172 pp.

Seven years after Edward Said’s death, we have the chance to reacquaint ourselves with the man, through David Barsamian’s The Pen and the Sword: Conversations with Edward Said. The book was originally published in 1994 with an introduction by Eqbal Ahmad, the late professor of Politics at Hampshire College. Nubar Hovsepian, Associate Professor of Political Science and International Studies at Chapman University, adds another introduction in the 2010 edition of the book.

The Pen and the Sword is a compilation of five interviews with Said, conducted by Barsamian, founder and director of Alternative Radio, over a period of eight years. Barsamian is also the author of numerous books with Noam Chomsky, Howard Zinn, Eqbal Ahmad, Tariq Ali, and Arundhati Roy.

In these interviews–“The Politics and Culture of Palestinian Exile” (March 18, 1987); “Orientalism Revisited” (Oct. 8, 1991); “Culture and Imperialism” (Jan. 18, 1993); “The Israel/PLO Accord: A Critical Assessment” (Sept. 27, 1993); and “Palestine: Betrayal of History” (Feb. 17, 1994)–Said and Barsamian wander over vast geopolitical, cultural, literary, and theoretical territories.

These interviews also introduce Said, the Palestinian-American intellectual and advocate for Palestinian rights, as the man whose scholarly and political activities were firmly rooted in his ideals and principles. Hovsepian gives some of the credit to Barsamian, noting, “Barsamian’s questions display his worldliness, which in turn allows Said to connect his humanism to his political engagements.”

Similarly, Ahmad, in the original introduction, held that “[The] book reveals more than any previous work the person behind the name… These interviews are unique for the connections they uncover between the man and his ideas.” In clear admiration, Ahmad wrote, “Edward Said is among those rare persons in whose life there is coincidence of ideals and reality, a meeting of abstract principle and individual behavior.”

Barsamian and Said’s compatibility, apparent in the interviews, and the deep respect each man held for the other is in part due to the historical and geopolitical circumstances of each of their peoples, the Armenians and Palestinians. “I feel a kinship with Edward Said rooted perhaps in my own background in which the themes of exile and dispossession were so prominent,” confessed Barsamian.

In fact, these men seem to have reached out for one another, in an effort to find support and a net to keep their struggles in motion. For instance, Hovsepian gratefully notes that “Edward introduced me to David Barsamian knowing that we could become kindred spirits in our capacity as the non-Armenian Armenians. Edward was right.”

Hovsepian’s introduction is as much a tribute to Edward Said as it is to Eqbal Ahmad and Ibrahim Abu-Lughod. “At two-year intervals, Eqbal then Ibrahim died. Then Edward died two years later, on September 25, 2003. Over a period of six years, we lost rare human beings who together represent the best of what public intellectuals should be. None of these men belong to the past alone,” wrote Hovsepian.

Said, who had been one of the first Palestinians to argue against Arab refusal to “recognize Israel’s existence,” argued that the most viable solution was through politics, and by recognizing that both groups were there to stay. For Said it was important to project a vision of Palestine that would attract both Palestinians and Jews, and to realize that vision with a “discipline of detail.”

Said met with both Israelis and American Zionists. “His very peaceability and accurate estimation of Zionism were perceived as serious threats by the Zionist establishment,” wrote Ahmad. “But what irked them most was his determined telling of the Palestinian story, his constant interventions with a ‘counterpoint,’ his quest for alternatives to sectarian nationalism.”

“Palestinians have the misfortune of being oppressed by a rare adversary, a people who themselves have suffered long and deeply from persecution. ‘The uniqueness of our position is that we are the victims of the victims,’” Edward Said told Barsamian.

Said was also a critic of the Palestinian leadership. In “The Israel/PLO Accord,” he took the opportunity to both attack the “Palestinian spokesmen” and the Western media: “The media have simply not performed. They have just been another, in my opinion, stupid chorus in its selection of voices and spokesmen and so forth, and alas, and I say this with great shame and unhappiness, the Palestinians reproduced exactly the right kinds of spokesmen to be a part of this chorus, people who in the past were Fanonists a matter of a week ago and have now changed and become advocates of Singapore and open markets and development. They do nothing for the real mass of the Palestinians, who are landless peasants, stateless refugees, cheap wage earners at slave labor, and this preserves the hegemony of the traditional families and the traditional leadership. So I think the media are enormously powerful. CNN has an incredible reach. But in terms of informing, it doesn’t. It simply confirms the world ideological system, now controlled, I believe, by the U.S. and a few allies in Western Europe.”

For Hovsepian, Edward Said, who was a professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University, was a truly cosmopolitan intellectual, with an unwavering allegiance to truth, and a critical eye towards modernity, willing to acknowledge both its successes and failures. “[Said’s] primary concern was to delineate the sources of Western knowledge about non-Western societies,” writes Hovsepian, noting that Gyan Prakash had once called Said “the quintessential oppositional intellectual,” compared with his colleague, Bernard Lewis, the “embedded intellectual” who serves power.

In The Pen and the Sword, the discussions take interesting turns. Among the topics are Said’s renowned book, Orientalism (1978), Palestine and Israel, Algeria, Albert Camus, Joseph Conrad, popular culture, Mahmoud Darwish, Jane Austen, Graham Greene, V. S. Naipaul, T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, and much more.

***

“Stephen Daedalus in Ulysses talks about history as ‘a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.’ When you’re awake what do you see?” asked Barsamian,

“I don’t think history’s a nightmare, unlike Stephen Daedalus,” answered Said. Real change “can only happen very slowly and as a result of education. … Without a self-conscious, skeptical, democratically minded citizenry, there’s no hope for any political change for the better, in this country or in the Middle East.”

Please review the new novel The Ghosts of Anatolia: An Epic Journey to Forgiveness by Steven E. Wilson