PTGHNI, Armenia—You would never meet Razmig Manoogian unless you hopped a cab and took a circuitous route outside of Yerevan over bumpy dirt roads and jagged crossings to a place in some God-forsaken village called Ptghni.

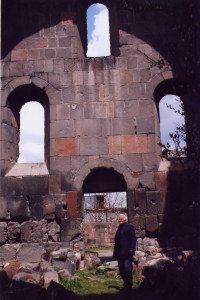

There you will find a church in ruins with a cow grazing amid the rubble. Hidden in an alcove off to one side is a venerable 70-year-old gatekeeper who makes it his business to greet visitors when and if they should ever appear.

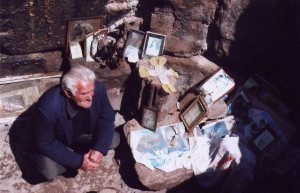

His sanctuary is rubble. He sits on a rock and waits, surrounded by icons in a personal retreat he has occupied over the past half century. Yes, he’s been coming here since the age of 20.

“I’m a very happy man,” he tells you. “I have Christ in my soul.”

Pronounced Pit-ga-nee, this church dates back to the 5th century about the time of Zvartnots and has laid in ruins over the past 600 years. It rests in the village by the same name and is somewhat of an icon for these townsfolk.

As for the cow, it’s like Mary and the lamb. Wherever Razmig goes, the cow is sure to follow—from a farm about 500 yards away which is home.

On a good day, a dozen curiosity-seekers may venture forth. In contrast, there have been days when only the spirits hover. It hasn’t the charm of Soorp Hripsime or Khor Virap, nor the pomp of Etchmiadzin. Ptghni offers a grim reminder of the past and is more apt to attract the curious-minded.

They are people like Joe Dagdigian of Harvard, Mass., with such an interest in archaeology that one visit would not suffice, let alone two. He could spend an eon studying the rocks and filling his pad with vital information.

“In all the years I’ve been here, I have not seen one priest,” Manoogian laments. “You would think the clergy might be attracted to this place. You might consider this my second home but I don’t see it that way. Ptghni is everybody’s home.”

It was cold on this day, enough for Manoogian to bundle up. He’s there in the rain, snow, and sleet. So is his “sacred” cow. Both are oblivious to the elements. The sounds of barking dogs and roosters crowing can be heard in the distance.

“In my heart, I believe this church is so very much alive, despite its fallen condition,” he adds. “A church is only rock. This is still the house of God and I feel His presence every day. So many churches in Armenia and Turkey have fallen into ruins. It doesn’t mean they should be forgotten.”

The urge to tidy up the grounds becomes repulsive. To move a single rock is sacrilegious in Razmig’s mind.

“It’s God’s way of telling us that despite the tragedy Armenia has undergone, we must rise above it,” he says. “When outsiders come here and see the pillage and destruction, to them it’s a spectacle—a shame.”

In his small hide-away, there are candles with melted wax, pictures of the Madonna and Child, a couple crucifixes. Like Razmig, all appear to have withstood the ravages of time.

He became a widower three years ago and lives on the farm with his family. Two sons, two daughters, and 11 grandchildren offer him all the comfort he needs. His parents hailed from Sassoun, much like the epic folk hero David.

“I wish to die in his spirit,” he reminds you.

There are no public facilities at this church. Whenever there’s an urge, Razmig dashes home, takes care of business, then comes back. The cow remains steadfast.

Throughout his life, he worked as a chauffeur and continues to remain a man of modest means. Talk to him about the government and it detonates an inferno.

“Armenia is not in a good situation,” he points out. “A lot of poverty and anguish prevail. Nothing much is being done to correct this. I personally would like to see Raffi Hovhanessian as the next president. He’s not only intelligent but compassionate toward the people. I have faith that Armenia will recover.”

It is Saturday at Ptghni, a very special day indeed. Short on visitors, Razmig is visited by his grandchildren. They light a candle, sit among the rocks, and share some stories. They are concerned about their grandfather’s welfare.

Fifteen hundred years of immortality is at Razmig’s pedestal. With his rosary beads in hand, he looks upward and offers a knowing smile.

“I’m in good hands,” he tells the children.

Beautiful depiction of a very special place and person. thank you for this.