German, French, English, and American Southerner—these were some of the pioneers of Illinois in the mid 1800s. It was to this colorful and diverse blend of cultures that the Armenians slowly came and joined the people that shaped Chicago.

Unobtrusively, like a sparrow’s nest perched in the branches of a towering pine tree, the Armenians in Chicagoland have quietly lived and worked in this vast and bustling midwestern metropolis, beginning in the latter half of the 1800s. A close-knit, family oriented people with a love for education and devotion to their Christian religion, they have blended well into Chicago’s “Melting Pot.” Yet, they have also maintained the rich heritage handed down to them from their forefathers who were from the foothills of Ararat, from the land called Armenia.

Although Armenians are predominantly Armenian Apostolic, with a small percentage being Protestant or Evangelical, and a smaller fraction Catholic, some of the earliest Armenian immigrants who came to Chicago were of the Protestant faith. Encouraged by American missionaries in Eastern Turkey—Western Armenia—to further their education in America, many came as students, while some came in search of jobs in order to make a better life for themselves and to provide for the families they left behind. Many of the immigrants believed that “one-day” they would return to their homeland, but “one-day” never came and they remained. Later, they came in order to escape oppression and the atrocities perpetrated against them by the Ottoman Turkish Government beginning in the 1890s and culminating with the Genocide of 1915. After the Second World War, Armenian DPs (Displaced Persons) in Europe, with the assistance of ANCHA (American National Committee to Aid Homeless Armenians), began arriving in the early 1950s. In the late 1950s and 1960s Armenians from the Middle East, particularly from Jordan and Lebanon, arrived due to war and political turmoil in those countries. In the late 1980s and 1990s Armenian immigrants from the former Soviet Union, particularly from Azerbaijan, where the small Christian Armenian minority was being persecuted and annihilated by the Azeries, found refuge here. During this period, Armenians from Armenia also began arriving because of political and severe economic difficulties in their country.

By 1895, approximately 300 Armenian immigrants lived in Chicago. Since the city was a great industrial center, it was not difficult for the immigrants to find work. During those early years, the immigrants, many of whom had been engaged in certain occupations in their homeland, worked in different occupations in Chicago. One barber became a baker, another became a real estate agent; an editor became a salesman; an electroplater became a physician; a stone carver became a photoengraver; one teacher became a tailor, another became a minister; a tobacco planter became a rubber worker; a veterinarian became a slide colorist. While some of the newcomers worked in professional capacities, many others worked in factories, mills, and slaughter yards. Some of those who worked as tanners in the leather factories came from a region in eastern Turkey known as Tinkoosh, and some of those that worked in the candy factories came from the regions of Kharpert and Tinkoosh. (Many Armenian immigrants who lived in Granite City and Waukegan, Illinois, found work in the iron and steel mills there, and in nearby Racine, Wisconsin, they found work in the furniture factories.) There were peddlers, oriental-rug shop owners, rug cleaners and menders. One oriental-rug shop that was established in 1920, Oscar Isberian Rugs, continues the legacy that began in Sivas, Turkey. There were furniture store proprietors, restaurateurs, grocery shop and lunch and coffee house owners. There were tailor shop owners and dressmakers. There were bakers, barbers, confectioners, cooks, hat cleaners, jewelers, laborers, machinists, schoolteachers, shoemakers, and waiters. There were artists (one of whom had become nationally renowned by 1919), clerks, firemen, painters, photoengravers, and policemen. There were manufacturers of cigars, candy, ice, milk products, jewelry, tools, and machinery. Within a relatively short period, a number of the immigrants established businesses, and the number of professionals grew. In the early 1900s, one of the physicians became the physician for the Chicago Public Schools. The Armenians then, as now, did not live in clusters in any particular area, but instead lived somewhat scattered throughout the city and suburbs.

During those early years in the latter 1800s and early 1900s, the Armenian immigrants, being so far from their homeland, speaking less in their mother tongue, must have felt what the Armenian painter Martiros Saryan had put into words. He had written, “The earth, like a living thing, has its own spirit, and without one’s native land, without close touch with one’s motherland, it is impossible to find oneself, one’s soul.” So, with their cultural heritage still fresh with them, the early immigrants worked long and hard, and sacrificed much in order to build an Armenian community that was strong and vibrant, where at last they could flourish, freely practice their Christian religion, and even speak in their mother tongue—all these things without fear, oppression, or even worse. They were energetic, idealistic, and filled with hopes and dreams for a better life. Mindful of the plight of those they left behind, the early immigrants never broke their ties with the land of their ancestors, always ready and willing to be of assistance both financially and morally. One of the ways the immigrants retained their link with their homeland and culture, as they adapted to life in their newly adopted country, was through music. At family gatherings, socials, and picnics they sang their songs and danced their dances to the rhythm of their homeland. As the years passed, their music, whether religious, festive, or solemn, continued and continues still to be an integral part of their lives, with each note, each word, and each step reinforcing their link with their heritage. Some of the songs that were written, particularly those of the 1920s, offer insight into the life of the immigrants. Many of the songs were of love, courtship and marriage, life in America, including pastimes, hardships, laments, and the homeland. For example, The Citizen is about a newly naturalized American citizen who visits the old country to meet with his betrothed. The song, sung in the Western Armenian dialect and played in the popular Armenian music style, begins:

Welcome, oh Citizen! Oh, a thousand welcomes to you!

I have waited impatiently for you for all these four years…

Oh, your hair has fallen out!

Your teeth have fallen out!

And your eyesight has gotten a little poor…

From the factory smoke you have turned yellow like a lemon.

You speak half Armenian, half English…!

And, Mountain Girl, sung in the Eastern Armenian dialect and played in the classic Armenian folk music style, is a melodic, lyrical song of love in the homeland. A young man, who is watching a mountain girl as she works “so much, so hard in the fields picking things, yet looking lovely and graceful,” croons:

Mountain girl, mountain girl,

As you pick in the fields,

You sing sad songs…

You are bright as the sun…

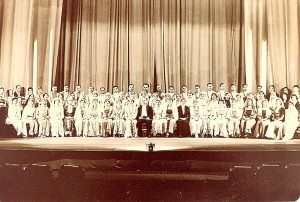

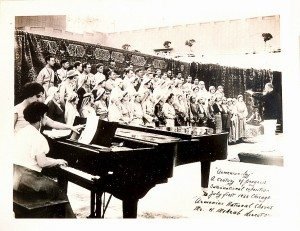

As members of their newly adopted country, the early Chicago Armenian immigrants participated in the various cultural events that the city offered. In 1893, during the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, a gifted young artisan, who had arrived from Marsevan, Turkey, just a couple of months prior to the Exposition, was invited to display his works—a violin and two lute-like instruments (the Saz)—at the Exposition’s Furniture Section in the Manufacturer’s Building. In 1933, the Armenians, along with a multitude of other nationalities from Chicagoland and throughout the United States, were invited to share their cultural heritage at the World’s Fair in Chicago. Dressed in traditional Armenian costumes, the Armenian National Chorus won First Place locally at the Nationalities Day event and Second Place nationally. The 70-member, male and female, choral group was comprised of individuals of various Armenian political persuasions—Dashnags, Hnchags, Ramgavars, as well as Independents. The conductor was the renowned Russian-Armenian music director Harout Mehrab. At the Plaza of Internationalism, each day a different country was recognized. There was an Armenian Day. The Armenian community, today, still continues to participate in the various cultural events the city offers.

Newly arrived Armenian immigrants encountered many difficulties and hardships common to most immigrants—acceptance by the new society, and even by their own nationals, being paramount. They had to familiarize themselves with new customs, traditions, and holidays. They had to adjust to the “aloneness” of American society, and to a variety of new foods, fashions, and even different ways of thinking, especially about themselves. In their occupied homeland, Armenians were considered to be less than second-class citizens by the Ottoman Government simply because they were Christians, gavours or infidels; whereas in America, this was not the case. Here, they could live freely, just like everyone else. Because their lives and history were replete with persecution and domination, it took the Armenian immigrants quite a while to shed their heavy cloak of fear and servility and feel truly safe in their newly adopted country. In order to overcome, to some degree, the haunting memories of the countless horrors they and their loved-ones had witnessed and suffered at the hands of their oppressors, the immigrants not only immersed themselves into work, but strived to become a part of American society, while still retaining their Armenian heritage. Many attended English classes, and most became American citizens. They established strong family units, emphasized self-sufficiency and the importance of education, and they built Armenian churches and community centers. Today, Chicagland’s Armenian community of approximately nine thousand has five churches. Neighboring Belleville, Granite City, and Waukegan, Illinois, have a total of four churches. They are:

· Armenian All Saints Apostolic Church

· Armenian Congregational Church

· Saint Gregory The Illuminator Armenian Apostolic Church

· Saint James Armenian Apostolic Church

· Saints Joachim and Anne Armenian Church

· Holy Virgin Mary and Shoghagat Armenian Church (Belleville)

· Saint Gregory The Illuminator Armenian Apostolic Church (Granite City)

· Saint George Armenian Apostolic Church (Waukegan)

· Saint Paul Armenian Apostolic Church (Waukegan)

Some of the primary organizations that were established in Chicagoland over the years are:

· Armenian Democratic Liberal Organization

· Armenian General Benevolent Union

· Armenian Relief Society

· Armenian Revolutionary Federation

· Hamazkain Culural Association

· Homenetmen Athletic Organization

· Knights of Vartan

· Tekeyan Cultural Association

The Chicago Armenian community’s primary Saturday Armenian language schools are:

· The AGBU Sisag H. Varjabedian Saturday Armenian School

· The ARS Taniel Varoujan Saturday Armenian School

The stories of the early Chicago Armenian immigrants are numerous, some of them ordinary, some of them poignant, and some of them inspirational. There is the story of the first recorded Armenian, and the story of the prolific Armenian author, popular lecturer, and firm believer in women’s rights, who between the 1890s and the 1920s, spoke to “more than 2,000 people every Sunday morning at Chicago’s Orchestra Hall.” There is the story of Chicago’s first Armenian priest who had come from Turkey, and the story of his son who was instrumental in establishing an Armenian library in the city and became the Chicago correspondent for the Armenian language, Boston based newspaper, Hairenik. There is the story of the Armenian justice-of-the-peace, who resided in Evanston, Illinois, in the 1920s, and the story of the young American boy of German and Irish descent from southern Illinois, who attributed his renown as a physician to the Armenian doctor who practiced in his neighborhood. Perhaps, one of the most poignant and inspirational stories is that of an Armenian doctor named Yepros.

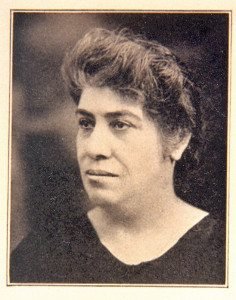

In the 1880s, a handful of Armenian physicians were already practicing in Chicago, and by the 1890s, the number had grown. By the early 1900s there were even more, among them Dr. Yepros Martin Doodakyan and her brother Dr. John Martin Lipson. (It is customary among Armenians, especially in Armenia, to use the father’s first name as the middle name for both sons and daughters alike. While Yepros had retained the family name, her brother John had translated it into English: Doodak meaning Lip, and yan meaning son or son of, hence, the name Lipson.) The Doodakyan family of Marash, Turkey—three sisters, a brother, and their mother were one of a number of Armenian families who, after surviving the series of massacres that began in the late 1800s in Turkish occupied Armenia, immigrated to America. Against a backdrop of bloodshed and destruction, the Doodakyan’s came to Chicago.

Gradually, the family, like most of the other Armenian immigrants, adjusted to their new life, and little by little they began assimilating into American society, enjoying their rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” In return, they contributed much to their adopted country. Since their early youth, Yepros and John had aspired to become physicians. Yepros, in particular, had dreamed of someday owning her own small hospital. After completing their education in Chicago, sister and brother became general practitioners, and by 1914, working diligently and living frugally, the two physicians purchased property in Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood and established their own hospital—Saint Paul’s Hospital. While Yepros and John ran Saint Paul’s and administered to the needs of their patients, their sisters Semagoul and Violet performed the daily hospital chores. Nurses were hired, most of whom were of German ancestry. Eventually, the five-bed hospital expanded into a thirty-five-bed hospital and served the community well for many years until Dr. Yepros Doodakyan’s death in 1937, when it was sold. Earlier, in 1921, Dr. John Lipson met with a tragic death during a robbery at a nearby drugstore. The Chicago Daily Tribune wrote of the incident, “Three whisky thieves shot and killed Dr. John M. Lipson… Two hours after the robbery the three were arrested in a saloon known as the ‘Pistol Inn’…”

Despite the atrocities Yepros experienced in her homeland, and the murder of her brother in America, she continued to devote her life to the sick. Many of the patients who came to her hospital were poor, and a great number were accident victims. Among the Armenians in the Chicagoland area, she was known as “The Armenian Doctor,” and they referred to Saint Paul’s Hospital as “The Armenian Hospital.” Among the people in her surrounding neighborhood, many of whom were impoverished, the doctor, a woman with dark, melancholy eyes, was greatly revered. Not only did she help the needy, she even honored the pleading wishes of a non-Armenian, indigent, young mother by adopting her child. She also encouraged and sometimes financially assisted medical students. The doctor never married, and died at the age of 62. At her funeral, a large number of mourners—colleagues, patients, friends, neighbors, the policemen of the area, and especially the poor—came to pay their last respects to the lady doctor they affectionately called “The Angel of Help.”

Dr. Yepros Martin Doodakyan’s story not only captures the essence of the trials and tribulations the Armenian immigrants endured and eventually overcame, but it also illustrates their appreciation and contributions to the society that offered them not only refuge but the opportunity to achieve that which they could only dream of.

This article appeared in the print version of the Armenian Weekly on July 5, 2008.

I have recently returned from 3 1/2 years in Armenia in the Peace Corps. I would like to visit an Armenian Church near the north side of Chicago, occasionally talk in Armenian to someone, and perhaps present a talk-slideshow on my life there.

Dear ,

The Miss Iraq Beauty Pageant it is coming near by and we would love to have Armenian Iraqi Contestant to participate in this Pageant.

Please try to help us to locate Armenian participant or contestant.

Waiting to hear from You as soon as possible.

the Beauty Pageant event Miss Iraq USA

Thank YOU

Betty

773-567-1900

We are looking to find an Armenian to be interviewed for our Oral History project on Immigration in Edgewater. The information follows:

The Edgewater Historical Society is doing a project on Immigrants in Edgewater. Edgewater is on the north side of Chicago between Foster Ave. and Devon – and from Ravenswood to the Lake. The project requires getting people to be interviewed who were born outside of the United States and who live in Edgewater. The interview would take about an hour and would be videoed in the Edgewater Library or our museum. We will schedule the interview for the beginning six months of 2014. Please contact Betty at 773/275-5349 or bmayian@sbcglobal.net .

Betty Mayian

Edgewater Historical Society

I am curious if there are other Armenian communities in Illinois besides Chicago? I know there is nothing in Galesburg, IL but I was curious about near the quad cities, to the Iowa area? Iowa is closer than Chicago for me and I’ve been picking up some Armenian language while I’ve been volunteering with the Birthright Armenia program, but I want to keep the language fresh in my mind and learn more in an Armenian community.

Hi if you want to keep Armenian language fresh you can visit the site and read and listen in Armenian. The language that use in Armenia.

https://www.jw.org/hy/

In case you speak Armenian West you can also visit this site.

https://www.jw.org/hy-latn/

I came to Chicago from Turkey 2 mounths ago. Now I am trying to find my relativies who are came from Erzurum Gezkoy Turkey between 1890-1898. My grandgrandmother is their lost sister (Rosa ). I know same stories abouth them. How can I find them? Please tell me a way….

I am looking for an Armenian interpreter in downtown Chicago in November for an Autism eval. Do you know anyone who would be able to assist?

I am looking for an Armenian contractor in the Chicago area. Please let me know if anyone interested.

Hello,

I am a linguist researcher. I am looking for people who speak Armenian and English to participate in my reading experiment. I will ask people to read sentences on my laptop and select answers to comprehension questions. The sentences will be very easy and I will only be interested in the time people need to read some words in the sentences.

If you would be willing to help me with my study, please email me at msokolopez@gmail.com or text 872-232-2567. We will choose a convenient place to meet. I will pay you back with a cup of coffee.

Marina.